Finest Hour 197

Something for Old Ireland

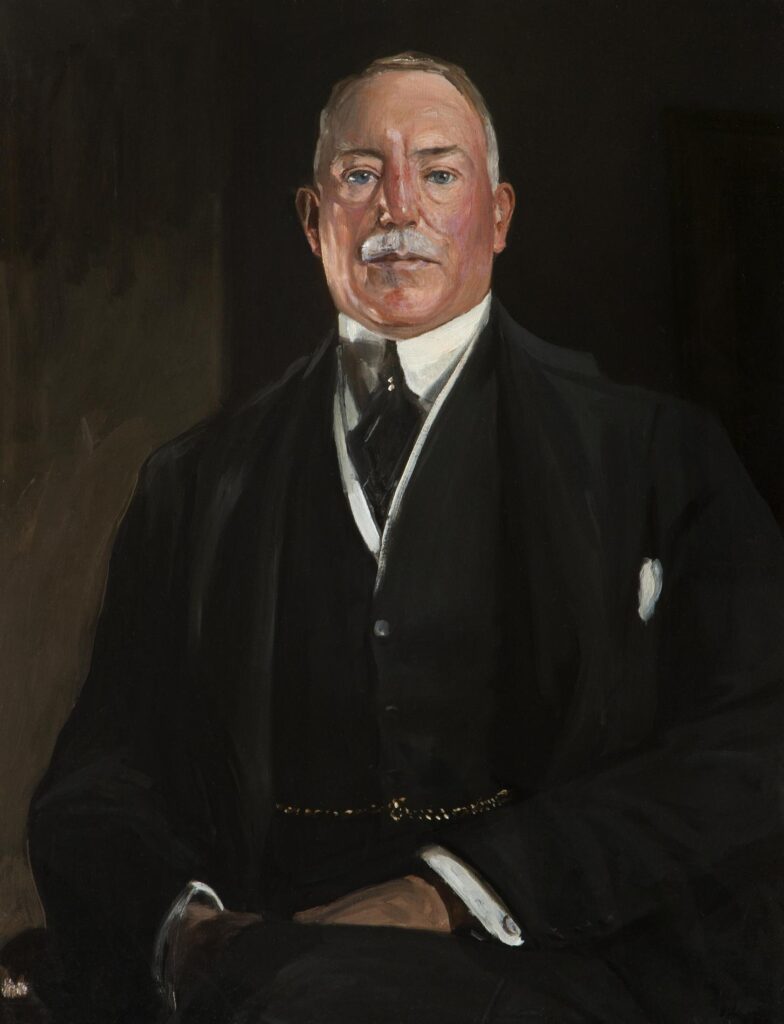

Sir James Craig

March 26, 2024

Winston Churchill and the Irish Settlement of 1921–22

Finest Hour 197, Third Quarter 2022

Page 19

By Ronan McGreevy

Ronan McGreevy is the author of Great Hatred: The Assassination of Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson MP, published by Faber & Faber and reviewed on page 46.

In a debate in the House of Commons a week after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, Winston Churchill mused on the outsized importance of Ireland to British public life. Ireland was a “small, poor sparsely populated island” with little in the way of natural resources. Its island status made it vulnerable to attack.

“It is a curious reflection to inquire why Ireland should bulk so largely in our lives. How is it that the great English parties are shaken to their foundations, and even shattered, almost every generation, by contact with Irish affairs?” he asked the House nine days after the signing of the Treaty.1

Churchill was an enthusiastic signatory to the Treaty. It was peace with honour, he believed, supported by “nineteentwentieths of the people of both countries.”2 This was characteristic hyperbole. There was a majority in both Great Britain and in the new Free State in favour of the Treaty, but nothing like that level of unequivocal support, certainly not in Ireland anyway.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Like most of his British contemporaries, he saw the Irish question as a problem created by Ireland for Britain rather than the other way around. In Britain the Treaty was greeted with a rare equanimity which stretched across government benches. On the same day Churchill delivered his speech, 16 December 1921, the House of Commons passed the Treaty by 401 votes to 58, the House of Lords by 166 to 47.

Great Britain had got much of what it wanted from the Treaty. It had lost its most troublesome region yet managed to retain it within the British Empire. Britain retained three naval bases in what would become the Irish Free State and acquired a guarantee that the new Irish state would not be used by Britain’s enemies as a bulwark against her. Churchill became the highest profile proponent of the Treaty and was ideally placed as Secretary of State for the Colonies to be chairman of the provisional government of Ireland committee.

The Irish View

The general sense of relief surrounding the Treaty was not matched on the other side of the Irish Sea. The Treaty was popular with the public at large. It voted overwhelmingly in support of pro-Treaty candidates during the first general election in the Irish Free State on 16 June 1922. The Treaty provisions, especially around the oath of allegiance to the British monarch, though, were bitterly contested among Irish republicans who had fought the War of Independence, also known as the Anglo-Irish War, between January 1919 and July 1921.

The Treaty narrowly passed the cabinet by four votes to three and the Dáil by 64 votes to 57, prompting a walkout by anti-Treaty leader Éamon de Valera and his followers.

The creation of the Northern Ireland state in May 1921 and the Irish Free State in December of that year was intended to solve the Irish question. In terms of creating polities to satisfy the national aspirations of the majority in both polities, the Treaty succeeded, but it left a disgruntled minority on both sides of the border.

Violence in the North between the minority Catholic population and the Unionist-dominated police got worse in 1922. That year would prove to be the bloodiest of the Belfast pogroms, an embryonic Troubles which pitted nationalists against unionists and republicans against Crown forces.

In the south too there was much unrest, though not on a comparative scale. Churchill brokered two pacts between the de facto leaders of Ireland, Michael Collins and Sir James Craig, to end the violence in the North.

The failed January pact was followed by one in March after the massacre of six members of the well-known Belfast Catholic McMahon family. “Peace is today declared,” Churchill boldly stated.3 The pact recognised the difficulties nationalists in the North had with the new state. Catholics were to be actively recruited into the Ulster Special Constabulary and there was to be a special police force in mixed areas of Belfast that would include equal numbers of Catholics and Protestants.

The IRA agreed to release the loyalists it held captive, and the Northern authorities those republicans who were currently in jail. The British government provided funding for relief work for any workers who had lost their employment. In addition, a number of committees were established to oversee and attempt to conciliate disputes, grants and employment. The problem for both Craig and Collins was that hardliners on both sides were determined to scupper the agreement.

Within hours of its signing, the IRA killed two children in a sectarian attack on Brown Street, Belfast. This was followed by ambushes on special constables in Newry and Belfast that left two more people dead. In retaliation, the police rampaged through the Stanhope Street and Arnon Street areas of Belfast on 1 April 1922, beating down doors.

Churchill became increasingly agitated about the failure of the Provisional Irish Government to stamp its authority south of the border.

Two IRA conventions, one in March 1922 and the other a month later, had repudiated the authority of the Irish parliament and its new government. There were now two putative armies in the South, each disputing the other’s right to exist.

Problems on All Sides

On 12 April 1922 Churchill wrote to Michael Collins, then chairman of the Provisional Government, pleading with that government to assert its authority:

It is obvious that in the long run the government, however patient, must assert itself or perish and be replaced by some other form of control. Surely the moment will come when you can broadly and boldly appeal not to any clique, sect or faction, but to the Irish nation as a whole.4

Churchill’s letter, written not as one politician to another, but from one man to another, underestimated the difficulties of legitimacy faced by the new Irish government.

The narrow passage of the Treaty and the absence of a popular mandate made it difficult for the Provisional Irish Government to move against erstwhile comrades. The new Irish government was famously described by its Minister for Justice Kevin O’Higgins as “eight young men standing amidst the ruins of one administration with the foundation of another not yet laid, and with wild men screaming through the keyhole. No police force was functioning through the country, no system of justice was operating, the wheels of administration hung idle, battered out of recognition by the clash of rival jurisdictions.”5

Neither did the Provisional Government have an appreciation of the difficulties faced by a Lloyd George government led by a Liberal with a Conservative majority. The cherished dream of an Irish Republic was out of the question as far as the British were concerned. They would later relent when a republic was declared in 1948, but that had been after twenty-six years of effective Irish independence, when the circumstances had changed completely.

The looming threat of civil war and the imminence of the Irish Free State’s first scheduled election saw a pact agreed between pro- and anti-Treaty factions within Sinn Féin.

Signing of the pact on 20 May 1922 was a huge relief to the whole country and appeared to avert civil war. Collins and de Valera agreed to a list of candidates in proportion to the outcome of the Treaty vote in the Dáil.

In a proportional representation system, they encouraged the electorate to spread their preferences and ensure a Sinn Féin majority. Under the terms of the Treaty the election had to go ahead by the end of June. It was agreed that the election would be regarded as a vote not on the Treaty, but on putting together a unity government.

The Respite That Wasn’t

“Throughout the country relief was profound,” the anti-Treaty historian Dorothy Macardle recorded in her seminal work The Irish Republic, published in 1937: “It was understood that the Treaty was not to be an issue in the elections decreed for June. Instead of being faced with the necessity of recording an immediate decision on this overwhelming question, the people were offered a chance to postpone their decision until the matter could be clarified and understood. Instead of being forced to choose at once between a government committed to empire and a government pledged to defend the Republic even at the risk of war, they were offered an opportunity of returning a coalition government pledged to peaceful conservation of the present national strength.”6

The British government, however, was not happy. Churchill declared that if republicans were to go into government without accepting the Treaty, the agreement would be forfeit. Article 17 declared that “The British Government shall take the steps necessary to transfer to such Provisional Government the powers and machinery requisite for the discharge of its duties, provided that every member of such Provisional Government shall have signified in writing his or her acceptance of this instrument” (italics added).7

In the House of Commons on 30 May, Churchill sought to reassure the members, without much conviction, that the pact was the best chance for peace in Ireland. He added in the most euphemistic language he could muster that, should the Treaty be forfeit, “the resources of our civilisation are by no means exhausted. Should the end be failure, this country would be in an immeasurably stronger position to resume the bloody struggle than it was before.”8

Churchill’s speech was intended not only for MPs but also for the two guests in the Distinguished Strangers’ Gallery who were in London to negotiate the Irish Free State constitution, Collins and the president of Dáil Éireann Arthur Griffith, the most enthusiastic proponent on the Irish side of the Treaty.

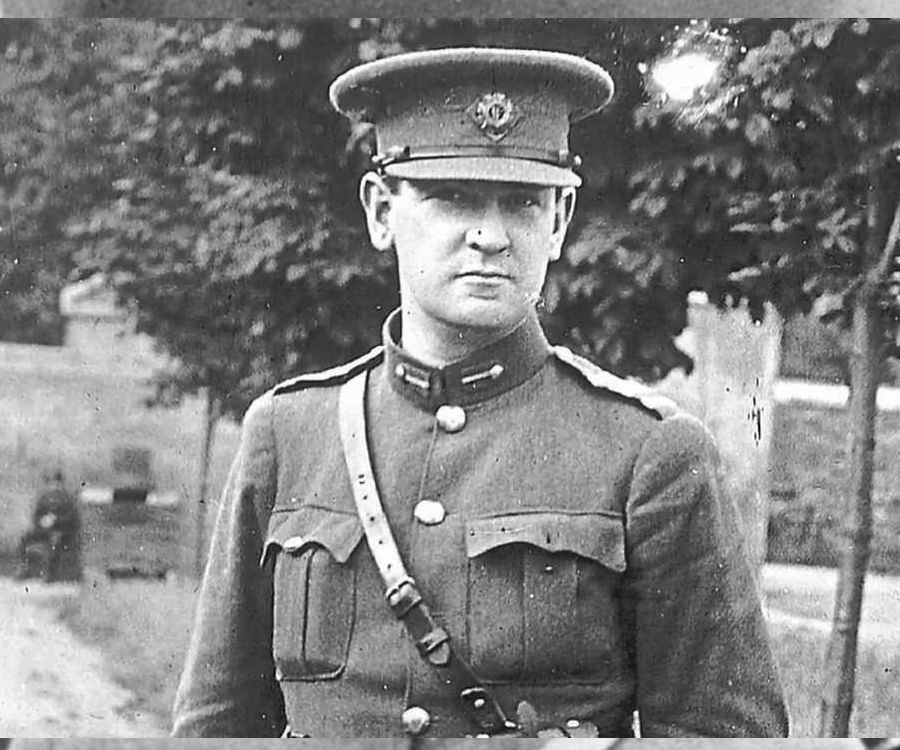

The two men also listened to Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, who had been elected an MP for North Down in February 1922. Wilson, a southern unionist from County Longford, had quickly emerged as the most vocal critic of the British government’s policy on Ireland. As Chief of the Imperial General Staff, the professional head of the British army between February 1918 and 1922, Wilson opposed any surrender to the “murder gang,” as he was wont to call the IRA and Sinn Féin, and regarded the Treaty as an abject surrender. In the House of Commons he repeated his criticism of the government in the same uncompromising terms:

If serious trouble arises on the frontier between the six counties and the twenty-six counties, I hope that the Government will not restrain the military from crossing the frontier in their own self-defence. I wonder when the moment will come when the Government will have the honesty and truthfulness to come to this House and to say, “We have miscalculated every single element in the Irish problem. We are exceedingly sorry for all the terrible things that have happened owing to our action. We beg leave to retire to private life, and never to appear again.”9

Wilson’s incendiary comments and his role as military adviser to Craig’s government made him a hated figure and a marked man among Irish republicans. Collins, who especially loathed Wilson, blamed him for the deaths of Irish Free State soldiers during clashes between British and Irish forces around the villages of Pettigo in County Donegal and Belleek in County Fermanagh in late May and early June 1922.

British troops used howitzers to remove a group of pro- and anti-Treaty forces from the Pettigo-Belleek triangle, which straddled the border. Ironically, it was Churchill, not Wilson, who ordered the British army into the area with the intention of teaching nationalist Ireland a lesson.

“Feverish Impetuosity”

Wilson’s assassination by two British-born veterans of the Great War who became IRA volunteers, Reginald Dunne and Joseph O’Sullivan, on 22 June 1922 laid bare the limits of British government toleration of the situation in Ireland. The assassination was blamed, conveniently as it turned out, on the anti-Treaty side holed up in the Four Courts.

The officer commanding British forces in Ireland, General Nevil Macready, was summoned to London that evening and found members of the cabinet spoiling for a fight. The most agitated of all was Churchill, whom Macready found to be in a state of “feverish impetuosity.” Macready played for time, afterwards explaining, “It can only be supposed that panic and a desire to do something, no matter what, by those whose ignorance of the Irish situation blinded them to possible results, was at the root of this scheme.”10

Nevertheless, in the House of Commons four days after the shooting, Churchill said in public what he had told the Irish in private: they would act against the anti-Treaty rebels if the Provisional Government did not. Churchill noted the results of the Irish general election, in which pro-Treaty candidates had won seventy-eight per cent of the vote. Here was a mandate, Churchill suggested, for the proTreaty side to assert its authority:

The time has come when it is not unfair, not premature, and not impatient for us to make to this strengthened Irish Government and new Irish parliament a request— in express terms—that this sort of thing must come to an end. If it does not come to an end, if either from weakness, from want of courage, or some other even less creditable reasons, if it is not brought to an end, and a speedy end, then it is my duty to say that we shall regard the Treaty as having been formally violated.11

Events intervened which made it easier for the Provisional Government to turn British guns on erstwhile companions. Just before midnight on 26 June, the anti-Treaty side captured the Free State general Ginger J. J. O’Connell in retaliation for the capture of an anti-Treaty officer, Leo Henderson. As a consequence the provisional government issued a proclamation: “Outrages such as these against the nation and the government must cease at once and cease forever. For some months past all classes of business in Ireland have suffered severely through the feeling of insecurity engendered by reckless and wicked acts which have tarnished the reputation of Ireland abroad.”12

Last Things

The Irish Civil War began on 28 June 1922 with the shelling of the Four Courts. Two months later Michael Collins was killed at Béal na Bláth, County Cork.

The Lloyd George government fell in October 1922, and the Conservatives called a general election for a month later. Churchill lost his seat in Dundee, swept away in an election which saw the end of the Liberals as a party of government in Britain.

Churchill was forty-eight. What should have been a peak of his political career proved to be one of the lowest points, though many Irish in the city did not forget his role in supporting the Treaty.

Some of his supporters gathered at the train station to see him leave a city he had represented for fourteen years. As the train readied to depart, Churchill told his Irish supporters: “Nothing has given me greater pleasure than the fact that during the last year that I have represented Dundee, I have been able to do something for old Ireland.”13

Endnotes

1. Hansard, House of Commons debates, 15 December 1921, vol. 149, cols. 133–258.

2. Ibid.

3. Hansard, House of Commons debates, 30 March 1922, vol. 152, col. 1690.

4. Diarmaid Ferriter, The Transformation of Ireland (London: Profile Books, 2004), p. 253.

5. Terence de Vere White, Kevin O’Higgins (Kerry: Anvil Books, 1966), pp. 83–84.

6. Dorothy Macardle, The Irish Republic (Dublin: Merlin Publishing, 1937), p. 714.

7. The text of the Anglo-Irish Treaty is at https://cain.ulster. ac.uk/issues/ politics/docs/ait1921. Htm.

8. Hansard, House of Commons debates, 31 May 1922, vol. 50, cols. 884–908.

9. Ibid., col. 2197.

10. General Sir Nevil Macready, Annals of an Active Life, 2 vols. (London: Hutchinson, 1924), vol. II, p. 340.

11. Hansard, House of Commons debates, 26 June 1922, vol. 50, cols. 1695–1705.

12. Michael Hopkinson, Green against Green: The Irish Civil War (Dublin: Gill Books, 2004), p. 44.

13. Anthony Jordan, Churchill: A Founder of Modern Ireland (Westport: Westport Historical Society, 1995), pp. 148–49.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.