Finest Hour 197

Books, Arts, & Curiosities

March 31, 2024

The Russian View

Finest Hour 197, Third Quarter 2022

Page 48

Review by Yigal Liverant

Yigal Liverant is a Ph.D. candidate in the Tel-Aviv University’s School of History specializing in the history of political ideas.

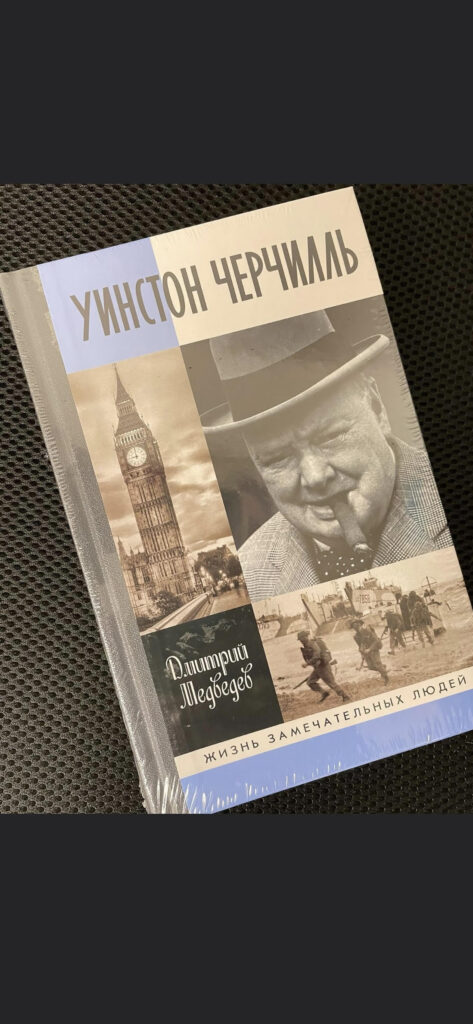

Dmitry Lvovich Medvedev, Winston Churchill, Molodaya Gvardiya, 2022, 489 pages. ISBN 978–5235045118

Much like Melville’s masterpiece, any Churchill biography should begin with the words “Call me Ishmael.” For, unlike most English Bible translations, the Hebrew original in Genesis 16:12 does not say “his hand against every man and every man’s hand against him,” but rather “his hand in every man and every man’s hand in him.” The confrontational aspect is still there, but God’s promise to Hagar speaks not only of future conflicts awaiting her son, but also of his infinite versatility, vigour, vivacity, and worldliness. This is no less true regarding the life and character of Winston Churchill.

For more than sixty years Churchill thrived at the centre of politics in one of the most political countries in the world. He participated in four wars on three continents, commanded at the highest levels in both world wars, pursued a Nobel prizewinning career as a writer, and lived a glamorous social life. Ah, and there is the additional matter of becoming the symbol of the firm Western stance in defense of the values of liberty and democracy against totalitarian threats. These are only the most general lines on his resumé, making the attempt to squash it into a single volume seem like a Herculean feat.

2024 International Churchill Conference

The Russian historian Dmitry Medvedev (not to be confused with the former president and current deputy head of the Russian Security Council) has done just that after spending more than twenty years researching Churchill’s character and publishing a dozen books examining the man and the statesman, including the monumental three-volume biography dedicated to the writing enterprise of his protagonist: Churchill: Speaker, Historian, Publicist (2016–2020).

Medvedev’s deep acquaintance with his subject is evident in this new Russian-language biography published in the veteran Russian series “The lives of unique persons.” Given Churchill’s versatility, this is an incredibly slim book. As the author writes on his personal website, although the length limits imposed on him by the publisher were frightening at first, he came to regard the seemingly impossible task as an interesting challenge “to write a single-volume biography of the British politician, presenting the personality as objectively and fully as possible.”

Medvedev has met the challenge with dignity. Indeed this is a highly readable and fairly comprehensive biography, which touches on the most important stations in Churchill’s life while managing to delve deeper into the two aspects the author has explored most over the years: Churchill’s managerial qualities and literary undertakings. Thus, the two areas most notably elaborated upon here are Churchill’s time as the First Lord of the Admiralty before and during the First World War and his conduct as Prime Minister throughout the Second World War.

A similar emphasis is placed on Churchill’s prolific literary career. Almost all of his books are reviewed, including Savrola, not a subject often given much attention. But here the protagonist of Churchill’s only novel is examined as the young author’s alter ego, “or rather,” writes Medvedev, “as one that Churchill might have become under a certain combination of circumstances.” Despite the notable resemblance between the author and the protagonist, Medvedev notes that the fictional Savrola chose to distance himself from active life and settle for the detached and pessimistic observer role, while Churchill was too much endowed with vigor, vitality, adventurism, and too strong a desire for action to retire from the field.

Medvedev’s brief overview of Churchill’s literary, historical, and political writings is rather appealing and enlightening, and especially convincing in its explanation regarding the role assigned to them by their author, who, much like Goethe, always believed that the active life is incomplete if not well surveyed and publicised. Churchill did not let his actions make the proverbial sound of a tree falling in an empty forest.

Medvedev’s brief, “history-of-everything” approach skips elegantly over the aspects that seemed to him less crucial in Churchill’s life. He eschews detailed descriptions in favor of macro-analysis and uses very few quotations. As a result, we learn little about Churchill’s private life (apart from his hobby of painting) or his relationships with his family (especially his daughters) and friends. Not even the intricacies of British politics and Churchill’s relations with Allied leaders Franklin Roosevelt and Josef Stalin receive in-depth attention. Medvedev sought only to write an introduction to Churchill, and this he has achieved admirably.

Given current conditions in Russia, Medvedev’s objectivity in covering his subject is almost an act of scholarly and civic heroism. When a modern Russian scholar writes about Winston Churchill, he takes on a unique symbol of the tensions between Western liberal democracy and Eastern autocracy, one who was endowed with complex attitudes towards Russia. True, Medvedev refrains from detailed discussion and historical judgment regarding the Russian issues that infuriated Churchill, and this does give the misleading impression that nothing special happened in Russia during Churchill’s life, either in the time of its terrible civil war or in the times of Stalin. Nevertheless, Medvedev does mention the dangers Churchill diagnosed in Russian Bolshevism.

Perhaps the one point of resentment Medvedev expresses towards Churchill is a rebuke for the fact that in the Prime Minister’s war memoirs “the Soviet Union’s struggle was given an offensively little space in the third and subsequent volumes of the hexalogy.” It is almost inconceivable, however, that a work of history can be published in Putinist Russia today without any complaints about “history being rewritten by the West,” especially “in order to diminish the role of the Soviet Union in the victory over Hitler.” This seems to be now an almost required statement in modern Russian historical publishing. That Medvedev was content with this single lament certainly does him honor.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.