Finest Hour 197

“A Deadly Moment in Our Life”

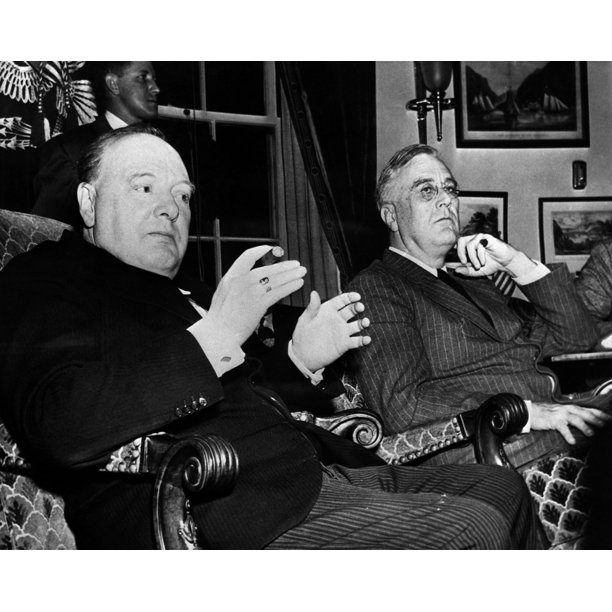

Churchill with President Roosevelt in the Oval Office

March 31, 2024

Churchill and Northern Ireland during the Second World War

Finest Hour 197, Third Quarter 2022

Page 35

By Karen Garner

Dr. Karen Garner is Professor of Historical Studies at SUNY Empire State College and author of Friends and Enemies: The Allies and Neutral Ireland in the Second World War, Manchester University Press, 2021 (see review p. 44).

It is no secret that Winston Churchill resented deeply that the twenty-six counties of Southern Ireland remained neutral during the Second World War, or that Churchill despised the Irish leader Eamon de Valera and his government’s obdurate refusal to ally with the British Empire and openly declare war against the Axis powers in 1939. With equal levels of emotion, Churchill appreciated the six counties of Northern Ireland’s “Unionist” loyalty to the British Crown throughout the war. In the early years of the conflict, Northern Ireland Prime Minister Lord Craigavon (formerly Sir James Craig) offered a critical territorial stronghold and material support and was willing to do much more to prove his country’s allegiance and worth to the British Empire.

Troubled Roots

In a failed attempt to subdue the long-running Irish national independence movement and avert a civil war, the British Parliament in 1920 passed the Government of Ireland Act that created two distinct Irish political entities: the six counties of Protestant-majority Northern Ireland with a devolved parliament but still a member of the United Kingdom, and the twenty-six counties of Catholic-majority Southern Ireland, with British Dominion status. The radical nationalist political party Sinn Fein and its military wing, the Irish Republican Army (IRA), rejected partition and continued violent campaigns for an independent Irish Republic encompassing the whole of the island. When the IRA attacked Northern Ireland’s government authorities, eliciting bloody reprisals from Crown forces and Union loyalists in October 1921, Prime Minister David Lloyd George assigned Secretary of State for the Colonies Winston Churchill to oversee negotiations to reconcile the warring parties.

Through the final months of 1921, Churchill led a British ministerial team in talks with Sinn Fein leaders Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, who headed a divided Irish delegation. After much debate on all sides, the resulting Anglo-Irish Treaty defined Southern Ireland as a “Free State,” self-governed by an all-Irish Parliament, the Dáil Eireann, with a place in the League of Nations. Northern Ireland remained within the United Kingdom, a nonnegotiable condition set by Craig. The British Navy retained its presence in the southwestern Irish ports, while the British Army withdrew forces from Southern Ireland and British government officials evacuated Dublin Castle. As a Dominion, the Irish Free State formally pledged its allegiance to the Crown.1 This last point elicited the most consequential dispute among the fractious Sinn Fein leaders, Eamon de Valera foremost among them. De Valera, not part of the London negotiating team, objected strenuously to the Oath of Allegiance and waged a heated campaign in the Dáil rejecting the treaty’s terms. Nonetheless, the delegation led by Griffith and Collins signed the treaty, dividing the leaders of the Southern government and the Irish people into two warring factions.2

2025 International Churchill Conference

The pro-Treaty faction hoped to avoid a renewed war with Britain, but border disputes between the North and South, along with IRA attacks on Belfast’s population, broke the peace in January and February 1922. Churchill again played a role in bringing Collins and Craig, as the leaders of the two Irish governments, to London to establish a Boundary Commission and to sign another fragile peace agreement. When Churchill’s interventions failed and IRA troops loyal to de Valera crossed the border to occupy Northern villages, Churchill lost patience and ordered British troops to eject the IRA. In the continuing violence between pro- and anti-Treaty forces, IRA operatives assassinated Collins in August. The Irish Civil War did not end immediately, but the Free State Provisional Government in Dublin that upheld the treaty terms held onto power. As successor to Collins, William Cosgrave continued to push for political solutions and to fight the anti-Treaty forces. This he did with the support of Churchill, then a Liberal MP, until the fall of 1922, when the Colonial Secretary lost his post as a new Conservative government came to power.

The 1921 Treaty dispute fueled the antipathy between Churchill and de Valera that continued as de Valera’s political fortunes rose again in the 1930s.3 While de Valera never stopped objecting to the pro forma Oath of Allegiance or partition of Ireland, he changed tactics in the mid-1920s and formed a political party, Fianna Fáil, that gained a majority of seats in the Free State Dáil in 1932. In 1937, as head of government, de Valera engineered the drafting of a new constitution that renamed the Irish Free State as the sovereign state of “Éire,” asserted in Article 2 that “the national territory consists of the whole island of Ireland, its islands and territorial seas,”4 and rejected the compulsory Oath of Allegiance.5 In 1938, de Valera negotiated a new Anglo-Irish Treaty with Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s Conservative government. The new treaty settled several outstanding trade disputes and returned to Éire’s control the British naval ports at Berehaven, Queenstown (renamed Cobh), and Lough Swilly. This was a serious error in strategic judgement according to Churchill, who was out of favor with Chamberlain’s government because he attacked the Conservative party’s overarching foreign policy of appeasing hostile powers to settle international disputes. In Churchill’s view, Britain needed those ports to defend its western shores in the coming war with the fascist powers, and Éire’s control of the ports enabled its declared neutrality policy.6

Divided Loyalties

When war broke out in September 1939, Éire remained neutral and Britain’s enemies, the Axis powers, retained their diplomatic legations in Dublin. With the British Navy banned from Éire’s ports, German submarines also gained greater freedom to patrol the North Atlantic and western approaches to Britain. Northern Ireland, a loyal member of the United Kingdom, played key wartime-support roles. Belfast provided laborers and a base for industrial manufacturing and shipbuilding, for which they paid a high price as targets of German Luftwaffe bombing attacks that were especially costly in terms of human lives and destruction of industrial infrastructure in April and May 1941.7 Even prior to the United States formally entering the war as Britain’s ally in December 1941, Northern Ireland allowed the Americans to build military bases and airfields in Ulster to accommodate US troops and equipment. The populations of both Northern Ireland and Éire were sources of volunteers who served in the British armed forces and in the war production factories in England. De Valera, however, effectively vetoed any military conscription orders issued by the British Parliament that included Northern Ireland. He rejected the partition of Ireland and continued “occupation” of Irish territory by the British. Before the war, Chamberlain’s government had issued a peacetime draft, but exempted Northern Ireland when de Valera resisted. Chamberlain again chose to appease de Valera rather than open up Northern Ireland to a renewed wave of anti-British violence.8

After the Belfast bombing in May 1941, the Luftwaffe extended its punishing attacks to London. Britain’s war making capacity was stretched to the limits. Now Prime Minister, Churchill announced his decision to extend conscription to include Northern Ireland’s population. Once again, de Valera, the IRA, and the IrishCatholic population living in the North vigorously rejected conscription. Churchill was no appeaser, and Irish objections to conscription infuriated him. Churchill reportedly told Éire’s Minister in London John Dulanty: “It makes my blood boil to think of your position. Ireland has lost its soul.”9 But Britain’s own diplomatic representative in Dublin, Sir John Maffey, also strongly cautioned the Dominion’s Office against enforcing conscription in Northern Ireland, predicting “draft riots, the escape of draft dodgers to Southern Ireland who will be acclaimed as hero martyrs by three-fourths of the population, and fermenting of trouble by representatives and fifth columnists…[and de Valera] will raise anti-British feeling and call for a Holy War.”10 In light of these apocalyptic predictions, caution prevailed. On May 27, Churchill announced that conscription orders for Northern Ireland had been dropped.

Partition: The Sticking Point

The conscription dispute was not the first time Churchill and de Valera fought over Northern Ireland’s status as a member of the UK. De Valera always rejected the “legality” of partition, even though he was forced to deal with the “fact” of Northern Ireland’s existence. In Churchill’s view, all of Ireland remained a vital part of the British Empire. When Britain went to war with Germany in 1939, then-First Lord of the Admiralty Churchill considered de Valera’s denial of Éire’s formal Dominion status and his government’s “right” to claim neutrality, to be illegal,11 “odious,”12 and, according to historian Eunan O’Halpin, “almost as a personal affront.”13 But in May and June 1940, given the seemingly unstoppable advance of German forces through the neutral powers of Norway, Denmark, Belgium, and the Netherlands, the debacle of the Allied retreat at Dunkirk, and the capitulation of France, Prime Minister Churchill needed to make an accommodation with de Valera in order to align all of Ireland with the anti-fascist powers. Under advice of his War Cabinet, Churchill sent a delegation to Éire in late June to negotiate an end to neutrality and clearance for the British Navy to occupy Ireland’s southwestern ports. Desperate times seemed to call for desperate measures, and the British delegates were authorized to put the possibility of ending partition at a future date on the negotiating table.

De Valera pushed back for the most extreme concessions—an immediate end to partition, all of Ireland to remain neutral, no British access to Irish ports but the US Navy could come into the ports to “guarantee” Irish protection from attacks by Germany or Britain—while first registering his outrage: “Great Britain had no right to attempt to barter the unity of the Irish nation for the blood of her people.”14 In Northern Ireland, when Prime Minister Craig heard of the negotiations he was just as adamant that his government would never agree to ending partition if it meant leaving the British Empire and succumbing to rule by a majority Irish Catholic government. Craig wrote to Chamberlain, who remained in Churchill’s War Cabinet after he stepped down as Prime Minister and who had put forth the proposals to offer an eventual end to partition to de Valera: “I am profoundly shocked and disgusted by your letter making suggestions so far reaching, behind my back and without pre-consultation. To such treachery to loyal Ulster, I will never be a party.”15 Craig sped to London to enlist Churchill’s support for his position, and he achieved his mission. Churchill insisted that Ulster must not be coerced into ending partition and Éire must agree to join the British war alliance; continued Irish neutrality would not be accepted.16 Thus, the 1940 negotiations stalemated. Éire remained neutral throughout the war, with de Valera resisting strong pressures from Britain and from Britain’s eventual ally, the United States.

Legacy

The ongoing Anglo-Irish conflict resurfaced as the war in Europe ended with Germany’s surrender in May 1945. Churchill recalled memories of Britain’s relationships with Éire and Northern Ireland during Britain’s darkest days in 1940 and into 1941 in a raw and emotional address to the nation on 13 May:

The sense of envelopment, which might at any moment turn to strangulation, lay heavy upon us. We had only the northwestern approach between Ulster and Scotland through which to bring in the means of life and to send out the forces of war. Owing to the action of Mr. de Valera, so much at variance with the temper and instinct of thousands of southern Irishmen, who hastened to the battlefront to prove their ancient valour, the approaches which the southern Irish ports and airfields could so easily have guarded were closed by the hostile aircraft and U-boats.

This was indeed a deadly moment in our life, and if it had not been for the loyalty and friendship of Northern Ireland we should have been forced to come to close quarters with Mr. de Valera or perish forever from the earth. However, with a restraint and poise to which, I say, history will find few parallels, we never laid a violent hand upon them, which at times would have been quite easy and quite natural, and left the de Valera Government to frolic with the German and later with the Japanese representatives to their heart’s content.17

Churchill expressed his active dislike for de Valera in very personal terms in this address, claiming that de Valera alone was responsible for preventing the Irish people from joining the British-led anti-fascist alliance, for withholding key resources and use of the Irish ports, and for “frolicking” with the Axis enemies in Dublin. British diplomat Malcolm MacDonald, who had been part of the failed negotiating team when Britain tried to entice de Valera to join the Allies in 1940, explained that Churchill’s colonialist mindset would never allow him to view de Valera as anything but “an enemy, an enemy, an enemy” of the British Empire.18 Churchill also condemned Éire on behalf of his nation: “their conduct [as neutrals] in this war will never be forgiven by the British people.”19 In contrast, Churchill’s ongoing support for Northern Ireland as “an integral part of the United Kingdom” was also ensured by Northern Ireland’s national allegiance and Prime Minister Craig’s personal loyalty to Britain during the war.

These wartime Anglo-Irish relationships, perhaps to the regret of the leaders whose influence over nations’ identities stretched long into the postwar era, in fact “solidified” the partition of Ireland that became “institutionalized” when British Parliament accepted the Dublin Dáil’s declaration of independence with the Ireland Act of 1949.20 At that time, Parliament also declared “that Northern Ireland remains part of His Majesty’s dominions and of the United Kingdom and it is hereby affirmed that in no event will Northern Ireland or any part thereof cease to be…without the consent of the Parliament of Northern Ireland.”21

Endnotes

1. Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life (New York: Henry, 1991), pp. 441–42.

2. Tim Pat Coogan, Eamon de Valera: The Man Who Was Ireland (New York: Harper Collins, 1993), pp. 280–81 and 292–96.

3. Anthony J. Jordan, Churchill: A Founder of Modern Ireland (Dublin: Westport Books, 1995), p. 163.

4. Eunan O’Halpin, Defending Ireland: The Irish State and Its Enemies since 1922 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 130.

5. Paul Bew, Ireland: The Politics of Enmity, 1789–2006 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 450–51.

6. Winston Churchill, Speech to the House of Commons on the “Éire Bill,” 5 May 1938.

7. Jonathan Bardon, “The Belfast Blitz,” in Dermot Keogh and Mervyn O’Driscoll, eds., Ireland in World War Two: Neutrality and Survival (Cork: Mercier Press, 2004), pp. 259–73.

8. Robert Fisk, In Time of War: Ireland, Ulster and the Price of Neutrality, 1939–1945 (London: Andre Deutsch, 1983), pp. 80–83. Northern Ireland Prime Minister Sir James Craig was anxious to prove his loyalty to the British government, but due to Catholic Nationalist resistance and IRA civil violence that de Valera “predicted” (or “threatened,” according to Craig’s report), Chamberlain refused to extend conscription to Northern Ireland in 1939.

9. John Day Tully, Ireland and Irish Americans, 1932–1945: The Search for Identity (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2010), p. 101.

10. Application of Conscription in Northern Ireland, Telegram from United Kingdom Representative to Éire (Maffey) to Dominions Office, 25 May 1941, CAB 66/2/47, British National Archives.

11. Fisk, p. 103.

12. Jordan, p. 171.

13. O’Halpin, p. 173.

14. Résumé of Talks between Taoiseach and Mr. Malcolm MacDonald, 28 June 1940, P150/2594, Eamon de Valera Papers on microfilm, University College Archives, Dublin.

15. Jordan, p. 174.

16. Fisk, pp. 177 and 187.

17. Winston Churchill, “Five Years of War,” Broadcast to the British Nation, 13 May 1945 (iBiblio, online information database, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill). http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/ policy/1945/1945-05-13a.html.

18. Fisk, p. 471.

19. Eunan O’Halpin, “The Second World War and Ireland,” in Alvin Jackson, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Modern Irish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 715.

20. Jordan, p. 188.

21. Ibid., p. 194.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.