Finest Hour 196

Churchill’s Official Visit to Palestine, 1921

Hebrew University on Mount Scopus today

June 14, 2023

Finest Hour 196, Second Quarter 2022

Page 27

By Fred Glueckstein

Fred Glueckstein is author of Sir Winston Churchill: Published Articles by a Churchillian (Xlibris, 2021).

In January 1921, Prime Minister David Lloyd George appointed Winston Churchill Secretary of State for the Colonies, commonly referred to as the Colonial Secretary, with special responsibility for Britain’s two Mandates, Palestine and Mesopotamia (Iraq).

Lloyd George explained that in both places Churchill’s main purpose was to reduce the cost of administering those distant and largely desert regions. With regard to Palestine, there was a second objective, no less important for the British Government. It was to carry out the terms of the Balfour Declaration and facilitate the establishment of a Jewish National Home. Churchill’s official trips as Colonial Secretary to accomplish Lloyd George’s directives included a memorable eight-day visit to Palestine in 1921.

Origins of British Administration of Palestine

Britain’s administration of Palestine was assigned by the League of Nations in the Mandate for Palestine in 1920. The mandate document encompassed the territories of Palestine and Transjordan, the lands west and east of the River Jordan respectively, both of which had been conceded by the Ottoman Empire following the end of the First World War in 1918. The mandate was given to Britain at the San Remo Conference of former wartime allies in April 1920.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Class A of the Mandate for Palestine included former Turkish provinces recognized as Palestine, Mesopotamia (Iraq), and Syria. The first two were assigned to the administration of Great Britain and the third to France.

The Articles of the Mandate for Palestine confirmed the intent of the 1917 Balfour Declaration, the statement of British support for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” It also included the special privileges granted to the Jewish community in Palestine, which had begun in 1918 with the appointment of the Zionist Commission headed by Chaim Weizmann. The commission looked after the interests of the small and impoverished Jewish community and made some official contacts with local and regional Arab political leaders.

By April 1920, Jews made up eleven percent of the population of Palestine, and anti-Zionist riots broke out in Jerusalem, killing several and injuring many. In July, the existing British military administration was replaced by a civilian administration led by Sir Herbert Samuel, who was Jewish, as the High Commissioner. Samuel proceeded to implement the Balfour Declaration and announced a quota of 16,500 Jewish immigrants for the first year.

To help Churchill focus on the Middle East, a Middle East Department was set up in the Colonial Office. John Shuckburgh, who had served for twenty-one years in the India Office political department, was head of its civil service.

Churchill also appointed T. E. Lawrence, known as Lawrence of Arabia, as his advisor on Arabian Affairs. Lawrence was renowned for his role during the First World War in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918) against the Ottoman Empire.

In April 1921, Churchill prepared to leave London for Cairo and Jerusalem to determine the nature of British rule in both the Palestine and Iraq Mandates. Churchill had set aside four weeks for the task, which included visits to Jewish towns and villages in Palestine.

Before Churchill left London, his three senior Middle East advisers—Lawrence, Shuckburgh, and Major Hubert Young, who, like Lawrence, had helped the Arab forces during the revolt against the Turks—informed him there was no conflict between Britain’s wartime pledges to the Arabs and to the Jews.

In 1915, the Arabs were promised “British recognition and support for their independence” in the Turkish districts of Damascus, Hama, Homs, and Aleppo—each of which was mentioned in the promise—but did not include Palestine or Jerusalem. Two years later, Britain promised a national home for the Jewish people of Palestine; however, there was no mention of specific borders.

Accordingly, if the land east of the River Jordan became an Arab state, and the land west of the Jordan up to the Mediterranean Sea became the area of the Jewish National Home, both of Britain’s pledges would be fulfilled.

The Cairo Conference

Churchill left London for Egypt on the evening of Tuesday, 1 March 1921. He travelled by train to Marseille and was joined there by Clementine. They continued by steamship to Egypt and arrived on Wednesday, 9 March.

When Churchill arrived in Cairo, he avoided a hostile demonstration by students who were waiting for him at the station by leaving the train a few miles outside the city and motoring to his hotel.1 Small sporadic anti-Churchill demonstrations took place in Alexandria on Tuesday and Wednesday.

The Cairo Conference began on Saturday, 12 March. The chief question to be discussed was the British mandates. During the conference, Churchill, who was accompanied by Lawrence, conferred with General Edmund Allenby, Sir Percy Cox, and Sir Herbert Samuel, respectively the High Commissioners for Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Palestine.2

On Thursday, 17 March, the decision was made was that the Transjordan region should indeed be separated from the rest of Palestine, as proposed by the Middle East Department and supported by Churchill. The dividing line would be the River Jordan. This decision enabled Britain to achieve its wartime pledges to the Arabs and Jews. Palestine, as it then became defined, included what today are the lands of both Israel and the West Bank.

Gaza

At midnight on Wednesday, 23 March, Churchill, Clementine, Samuel, and Lawrence left Egypt by overnight train for Jerusalem via Gaza in Palestine. In what was then known as Western Palestine, 83,000 Jews and 600,000 Arabs lived between the Mediterranean Sea and River Jordan. No Jews lived east of the river.

Martin Gilbert describes the purpose of the visit: “Churchill’s principal objective in going to Jerusalem was to explain to Emir Abdullah the decision of the Cairo Conference, and of the British Government, that Britain would support him as ruler of the area of the Mandate lying east of the River Jordan—hence its name, Transjordan—provided that Abdullah would accept a Jewish National Home within Western Palestine, and do his utmost to prevent anti-Zionist agitation among his people east of the Jordan.”3

On the morning of Thursday, 24 March, Churchill’s train reached Gaza, the first large town within the southwestern boundaries of the Palestine Mandate. Churchill, Clementine, Samuel, and Lawrence were met by an honor guard of British police at the railway crossing. A mounted escort took them to Gaza City.

There was a tremendous reception for Churchill by a loud crowd that was shouting in Arabic “Cheers for the Minister” and for Great Britain. Their chief cries, however, were “Down with the Jews” and “Cut their throats.” Churchill and Samuel were thrilled with the passion of their reception, but unaware of what was being shouted.

Gilbert wrote that Lawrence, who spoke Arabic, understood the shouting, but did not tell Churchill. Although Lawrence was extremely anxious, the tour of the town went on as planned surrounded by the mob that was becoming more agitated. To Lawrence’s relief, the visit to Gaza City ended without incident.

On Friday, 25 March, despite a ban by British Mandate authorities on all public meetings during Churchill’s visit, there were Arab demonstrations in Haifa to protest against any further Jewish immigration.

When the authorities attempted to break up the demonstrations, violence ensued. Ten Jews and five policemen were wounded by knives and stones. Two innocent bystanders, a young boy and a Muslim woman, were killed.4

Jerusalem

After leaving Gaza, Churchill took up residence in Government House on the crest of Mount Scopus in northeast Jerusalem. Churchill worked for three days preparing to listen to both Arab and Jewish representatives and to answer their respective requests.

Churchill observed that Mount Scopus provided the most beautiful panoramic view of the Old City of Jerusalem. As an ardent amateur artist, he arranged his easel and painted the sunset over the city.

On Sunday, 27 March, Churchill went to the British Military Cemetery on the Mount of Olives, a mountain ridge east of and adjacent to Jerusalem’s Old City, to attend a service of dedication.

The cemetery was established after the conquest of Jerusalem at the end of 1917. It contained the graves of 2,180 British soldiers, 143 Australians, fifty South Africans, forty British West Indians and thirty-four New Zealanders, as well as sixty men whose bodies were unidentified, and several German and Turkish prisoners.

In his short speech after the service, Churchill said: “These veteran soldiers lie here where rests the dust of the Khalifs and Crusaders and the Maccabees. Peace to their ashes, honour to their memory and may we not fail to complete the work which they had begun.”5

On Monday, 28 March, Churchill received Emir Abdullah at Government House. Abdullah feared that a high number of Jews would immigrate to Palestine and dominate the existing Arab population. Churchill sought to put Abdullah’s mind at rest.

As a result of his fruitful meetings with Abdullah, Churchill reported to London that Transjordan would become an Arab kingdom ruled by Abdullah, and that Western Palestine, from the Mediterranean to the Jordan River, would be ruled by Britain, with a commitment to continued Jewish immigration.

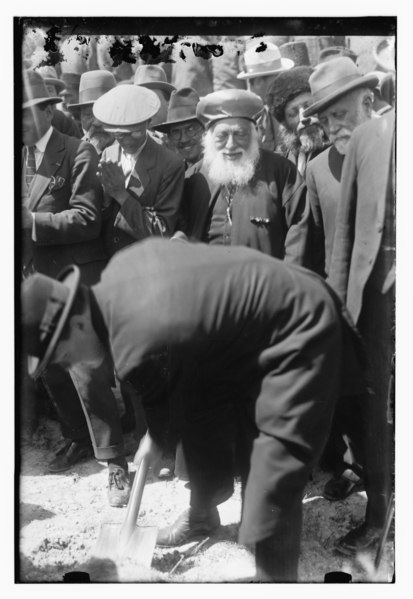

On the afternoon of Tuesday, 29 March, Churchill visited the building site of the future Hebrew University on Mount Scopus. Chief Rabbis Avraham Isaac Hacochen Kook and Yaakov Meir presented Churchill with a Torah scroll. Before planting a tree, Churchill spoke words of inspiration in front of 10,000 people.

“Personally, my heart is full of sympathy for Zionism. This sympathy has existed for a long time, since twelve years ago, when I was in contact with the Manchester Jews. I believe that the establishment of a Jewish National Home in Palestine will be a blessing to the whole world, a blessing to the Jewish race scattered all over the world, and a blessing to Great Britain.” Churchill continued, “I firmly believe that it will be a blessing also to all the inhabitants of this country without distinction of race and religion. This last blessing depends greatly upon you.”6

Tel-Aviv and Rishon Le-Zion

On 30 March, Churchill left Jerusalem. Prior to catching the evening train to Egypt from the railway junction at Lydda, Churchill had time to see two of the most notable Jewish achievements in Palestine. They included the twelve-year-old Jewish town of Tel-Aviv, next to the ancient and mainly Arab town of Jaffa. The second was the thirty-nine-year-old agricultural colony of Le-Zion.

Since the newly planted trees were not yet full grown in Tel-Aviv, Mayor Meir Dizengoff, who was anxious to impress Churchill, borrowed mature trees from neighboring areas and stuck them into the middle of Rothschild Boulevard, which was just beginning to be formed. Initially, they say, Churchill was amazed at the sight of such lush development having happened in such a short time.

Churchill burst into laughter, however, after local children climbed the trees to see the esteemed visitor—and the trees collapsed. While patting the shoulder of an embarrassed Mayor Dizengoff, who had presided over the growth of the city since its foundation two decades earlier, Churchill made a kindly remark about the importance of having roots.7

Speaking in Tel-Aviv with the mayor present, Churchill said how glad he was to have seen “the result of the initiatives of its inhabitants in so short a period during which, too, the war had intervened.”8

Afterwards, Churchill briefly stopped at Sarafend. There he met a group of new immigrants from Russia, who were working at road building. It was the first large public works undertaken by the Mandate authorities using Jewish labor.

From Sarafend, Churchill was driven ten miles to Rishon Le-Zion, which was Hebrew for “the first in Zion.” One of the oldest Jewish agricultural villages in Palestine, Rishon Le-Zion was established four decades earlier during the Turkish era. As Churchill approached the village, between fifty to sixty young people greeted him while galloping on their horses.

When Churchill and his entourage reached the center of the town “there were drawn up three hundred or four hundred of the most admirable children, of all sizes and sexes, and about an equal number of white-clothed damsels. We were invited to sample the excellent wines which the establishment produced, and to inspect the many beauties of the groves,” Churchill remembered.9

Churchill was greatly impressed by what he saw and heard about how perilous the work of the farmers could be, and how essential it was for Britain to protect them. On his return to Britain, he told the House of Common:

I defy anybody, after seeing work of this kind, achieved by so much labour, effort and skill, to say that the British Government, having taken up the position it has, could cast it all aside and leave it to be rudely and brutally overturned by the incursion of a fanatical attack by the Arab population outside….I am talking of what I saw with my own eyes.10

Churchill was in Palestine for eight days. It would be his only official visit to the Holy Land. During his time there, he recognized the fervor of the Jews and the hostility of the Arabs against them. As a result of Churchill’s successful meetings with Abdullah, the Transjordan became an Arab kingdom, and Western Palestine, from the Mediterranean to the Jordan River, was established as a Jewish National Home. Churchill’s accomplishment in Palestine in March 1921 would be the prelude to the establishment of Israel in May 1948.

Endnotes

1. “Killed in Egyptian Riot. Three Fatalities Follow Firing by Police on Anti-Churchill Crowd,” The New York Times, 12 March 1921, p. 7.

2. “Churchill to Visit East. Will Discuss Mandates for Palestine and Mesopotamia,” The New York Times, 19 February 1921, p. 2.

3. Martin Gilbert, Churchill and the Jews (London: Simon & Schuster, 2007), p. 52.

4. William Manchester, The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill, Visions of Glory 1874–1932 (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1983), p. 703.

5. Gilbert, p. 55.

6. Ibid., pp. 56–57.

7. Aviva and Shmuel Bar-Am, “When Rothschild Boulevard Put Down Roots and Declared Independence,” The Times of Israel, 5 July 2014.

8. Gilbert, p. 64.

9. Ibid., p. 66.

10. Ibid.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.