Finest Hour 192

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – Diverse Trio

December 30, 2021

Finest Hour 192, Second Quarter 2021

Page 44

Review by Cita Stelzer

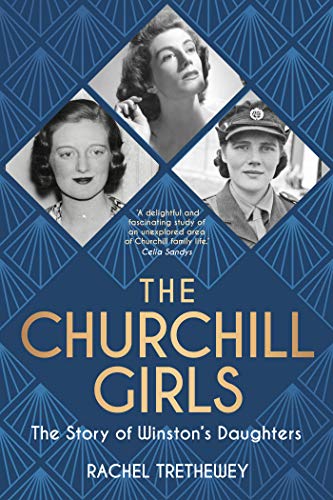

Rachel Trethewey, The Churchill Girls: The Story of Winston’s Daughters, The History Press, 2021, 320 pages, £14.32/$29.61. ISBN 978–0750993241

Cita Stelzer is author of Working with Winston (2019).

Rachel Trethewey’s The Churchill Girls: The Story of Winston’s Daughters proves, an enormous Churchill literature notwithstanding, that there is always more to learn about a man who lived a long life that often dominated the world stage, as well as about his “girls.” Far from feeling neglected by his frequent absences, Diana, Sarah, and Mary adored him. Equally important, the girls loved and supported each other throughout their lives. Sadly, another daughter, Mari-gold, died shortly after her second birthday.

Diana was born in 1909, and, continuing a tradition that her parents had started with each other, was nicknamed the Puppy Kitten, or PK. Winston was then President of the Board of Trade. As was usual in that era, Clementine recuperated separately in a cottage in Brighton, leaving PK with a nanny and Churchill to care for the baby. We learn a good deal about Churchill as a father from a letter I found in another source. Writing to Clementine on Board of Trade stationery, he reported that “The PK is very well—but the nurse is rather inclined to glower at me as if I were some tiresome interloper. I missed seeing [her] take her bath…but tomorrow I propose to officiate.” Diana was then six weeks old. After the Second World War, Diana worked tirelessly for The Samaritans. Tragically, following several emotional setbacks, she took her own life.

Two years after Diana was born, Clementine gave birth to a son, Randolph, when Churchill was serving as First Lord of the Admiralty. Randolph was to prove not the easiest going of the clan, at times requiring his sisters to join his indulgent father in defending him from his many critics. When kidnappers attempted to snatch the two infants, but were foiled by an alert nanny, security surrounding them was tightened.

In October 1914, Sarah, “the Bumblebee,” was born at Admiralty House. Winston, who had been in Antwerp, arrived a few hours after Sarah’s birth. She became the daughter who most sought the spotlight, eager for fame other than as a Churchill, as a dancer and actress. Her father would pull “strings to try to get her acting roles,” which proved to be a success both in Britain and in Hollywood. Sarah worked throughout the war years as a WAAF, at a top-secret military base rather like Bletchley Park, interpreting aerial photos for bombing assignments. Two men she loved committed suicide, but tragedy and marital failures did not dim her vivacity and charm, which captivated almost everyone who met her.

Finally, in September 1922, along came Mary, Baby Bud, the most balanced and best-adjusted according to Trethewey. Mary’s idyllic childhood at Chartwell was marred only by her father’s refusal to allow her to climb to the tree house he had built for her older siblings. She spent the war as a gunner in an anti-aircraft battery. Mary knew what she wanted and got it: a family of her own and a huge menagerie.

Trethewey does not overlook the tragic aspects of the girls’ lives, and of their parents’. But the death of Marigold, the difficulties faced by Sarah that once resulted in her arrest for drunken behavior and led her to rely on what she called the “protecting wings” of the family, and the suicide of Diana somehow seem not to have dimmed the joy the girls brought to Winston’s life, although they added to the strains on the always anxious Clementine.

Winston benefitted enormously from the girls’ company and care on his many travels. Diana accompanied him to the South of France, Sarah travelled with him to the Teheran and Yalta conferences and when he fell seriously ill after Teheran “knew that her nurturing skills were…to be tested to the limit.” Mary served as his aide at the Potsdam Summit, where she personally arranged the flowers for the dinner party with President Truman. And after the loss of his prime ministerial office in 1945, they all rallied to their father’s side—as they had done during his wilderness years. Sarah travelled with him to Lake Como and learned a lesson she said she would never forget. He said to her, “the most valuable piece of experience I can hand on to you is how to command the moment to remain.”

Churchill endowed his daughters with many of his own characteristics: patriotism, a work ethic, an understanding that family loyalty and bonds are essential, tenacity, resilience, and the famous Churchill magnanimity. As Trethewey explains, “they inherited this spirit of generosity from him. It is remarkable how rarely in their letters there is a vindictive comment about anyone….”Trethewey’s superb archival research job demonstrates that Churchill was his girls’ “lodestar,” and they were his pride and comfort. On Churchill’s seventieth birthday, in 1944, he acknowledged his love for them, toasting them “as the greatest there are.” A decade later, in 1954, he wrote to Clementine, “it is a lovely home circle and has lighted my evening years.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.