Finest Hour 192

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – Key Canadian

December 28, 2021

Finest Hour 192, Second Quarter 2021

Page 46

Review by Terry Reardon

Terry Reardon is the author of Winston Churchill and Mackenzie King: So Similar, So Different (2012).

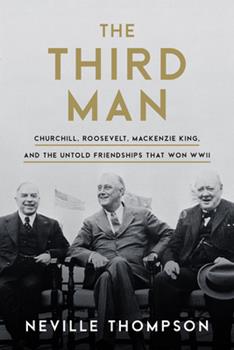

Neville Thompson, The Third Man: Churchill, Roosevelt, Mackenzie King, and the Untold Friendships That Won WWII, Sutherland House Books, 2021, 484 pages, CAN $39.95. ISBN 978–1989555262

While acknowledging that the dominant politicians among the Western Allies in the Second World War were Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt, Neville Thompson makes a case that the Canadian prime minister also played an important role.

W. L. Mackenzie King was an unlikely leader. He was introverted and cautious but remarkably successful. When he retired in 1948, he had been prime minister for twenty-one years altogether, a record for longevity in all of British and Commonwealth history.

2024 International Churchill Conference

King also kept a diary in which he recorded his thoughts, feelings, and happenings, including his meetings and communications with Churchill and Roosevelt. Thompson states that this “remarkable diary consists of 30,000 typewritten pages, about 7.5 million words….. It begins in 1893…and continues up to three days before his death in 1950.” The diary is the central source for this book, with Thompson opining that Churchill and Roosevelt would not likely have been so frank, especially as concerns each other, if they had known that their remarks, often confidential, would be recorded for posterity.

King had achieved prominence as Canada’s first Minister of Labour in solving industrial disputes. It was natural that he would be a strong supporter of Neville Chamberlain’s policy of appeasing Hitler and deeply suspicious of the orations of Churchill, which King thought would incite war. When Churchill became prime minister, however, King pledged Canada’s full support, and his opinion of Churchill rose to hero worship as the war progressed.

King was also at first suspicious of Roosevelt and the New Deal, which he considered “half-baked.” When the two men met officially for the first time in 1934, however, King succumbed—as most did—to the President’s charm, and a trade agreement was satisfactorily completed.

When the Second World War broke out, and especially after Churchill became prime minister, King became, as Thompson states, a reluctant go-between for the British and American leaders. Roosevelt was not at first confident that Britain would survive, and he asked King to lead the Dominions into pressuring Churchill not to make a soft peace with Germany. If defeat were likely, the President wanted the British fleet to be “dispersed to the empire,” but he did not want this idea to be seen coming from himself. King saw this as a selfish ploy for the United States to save itself. Although he did contact Churchill, King made it clear that it was the President’s entreaty and affirmed that Canada was determined to give all in its power to the Allied cause.

After the “miracle” of Dunkirk and the attack on the French fleet to ensure it did not fall into German control, Roosevelt adopted a more positive stance. In August 1940 he announced that his administration was discussing acquiring naval and air bases from Britain to protect the western hemisphere in exchange for old US Navy destroyers. The President also invited King to meet with him in Ogdensburg, New York to discuss the joint defence of North America. The result was that each country committed to protecting the other, and a Joint Permanent Board on Defence (which still exists) was established.

In early 1941, King was faced with a serious economic problem, of which Thompson includes a detailed account. Canada, which was the lifeline keeping Britain alive, had built up a huge trade deficit with the United States, mainly for war production. King had been reluctant to accept Roosevelt’s repeated invitations to visit him but realized that a direct meeting was necessary. This was held at the President’s personal home, and the subsequent “Hyde Park Agreement” ended Canada’s financial difficulties for the duration of the war.

After Churchill and Roosevelt began meeting directly starting in August 1941, King’s services as a go-between were no longer required, but, as Thompson writes, both Churchill and Roosevelt were eager to retain a close relationship with King, whose opinions they valued.

King’s friendship with the British and American leaders continued throughout the war and, in Churchill’s case, afterwards. Following the President’s death in April 1945, King was the only member of a foreign government to be present at the interment. He appeared, however, as a friend and not in an official capacity.

In this highly readable book, Thompson does not attempt to provide a detailed account of Canada’s important contribution to the war effort, but he does succeed in his primary objective. While King was not a central figure in the war when compared to Churchill and Roosevelt, he did play a significant part in the successful outcome.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.