Finest Hour 188

“The Main End of English Statecraft”

Edward Heath while in office

November 24, 2020

Finest Hour 188, Second Quarter 2020

Page 39

By Timothy Riley

Timothy Riley is Sandra L. and Monroe E. Trout Director and Chief Curator at America’s National Churchill Museum.

World leaders regularly visit Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, a small town of 12,000 people with an enormous ability to attract heads of state. Winston Churchill’s historic appearance in Fulton, of course, stands above all others. His “Sinews of Peace” speech, delivered on 5 March 1946, was one of the first salvos in the Cold War and set the stage for others to comment upon world affairs from one of the unlikeliest of places in the center of America. The importance of Churchill’s address, commonly called the “Iron Curtain” speech—and known worldwide simply as the “Fulton Speech”—paved a path for other leaders to follow. Presidents Harry S. Truman, Gerald R. Ford, George H.W. Bush, and Ronald Reagan all journeyed to and spoke in Fulton (Bush twice and Truman on three occasions). Furthermore, Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson were inducted as Churchill Fellows of Westminster College and served, with Truman, as honorary co-chairmen of the Winston Churchill Memorial and Library, rechristened “America’s National Churchill Museum” by act of Congress in 2009. Even two notable leaders born behind the Iron Curtain, Polish President Lech Walesa and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, have spoken here, offering observations and opinions on world affairs.

Special Relationship

While leaders throughout the world have descended, and continue to descend, upon this small Missouri town, those who succeeded Churchill as prime minister of the United Kingdom are linked more often to Fulton than those from any other nation. As early as 1903, Churchill pondered the concept of a “special relationship”—a phrase he would make famous in Fulton more than four decades later. “I have always thought that it ought to be the main end of English statecraft over a long period of years to cultivate good relations with the United States,” Churchill said in the House of Commons.

Three year earlier, in December 1900, Churchill had been introduced by Missouri’s most famous son, Mark Twain, before a lecture at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City. So to the young Churchill, it was most likely that Manhattan and Washington came to mind when he contemplated “good relations with the United States.” It was certainly not Fulton—at least, not until a half century later, when Missouri’s second-most famous son, Harry S. Truman, introduced the statesman before the “Iron Curtain” speech in the gymnasium of Westminster College.

Association of Churchill Fellows

In the long wake of the “Iron Curtain” speech, Fulton became a hot spot for prime ministers seeking to strengthen Anglo-American relations and address global affairs of great importance. Not even Churchill could have foreseen that so many of his successors in Downing Street would find themselves linked to an American college that shares a name with the palace that houses the British Parliament.

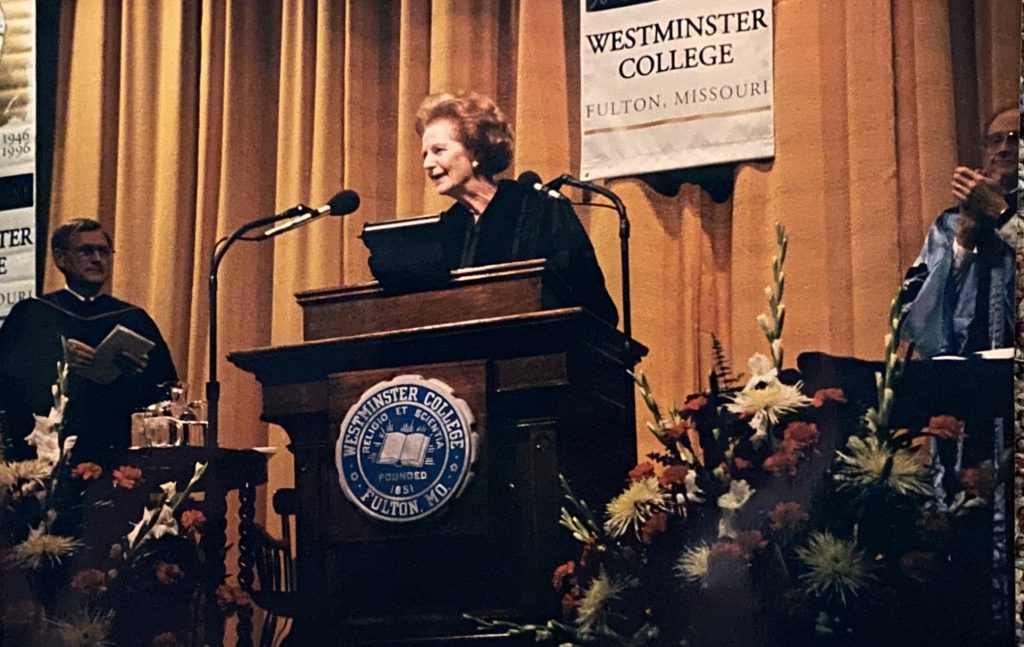

Photo: America’s National Churchill Museum Archive

The Association of Churchill Fellows recognizes leaders in industry, commerce, statecraft, and the arts and sciences. Seven Churchill Fellows so far have been among those who have succeeded Churchill as prime minister: Clement Attlee (awarded posthumously in 1969), Harold Macmillan, Sir Alec Douglas-Home, Harold Wilson, Edward Heath, Margaret Thatcher, and John Major. Additionally, Major—the only one of the seven who did not also serve in the House of Commons with Churchill—was awarded the College’s Winston S. Churchill Leadership Medal in 2008.

Like Churchill before them, Heath and Thatcher also delivered Westminster College’s John Findley Green Foundation Lecture. Both leaders were quick to recognize the importance of the location on the world stage due to Churchill’s legacy. While Churchill’s address still looms largest, his successors also made a mark with “Fulton Speeches” of their own. The full text of these speeches can be found on the museum’s website www.nationalchurchillmuseum.org, but several excerpts here follow.

Edward Heath

Former Prime Minister Edward Heath visited Fulton in 1982, a time when tension between the Soviet Union and the West was high and relations were perilous. Heath used the Fulton platform to make a plea for stronger interpersonal dialogue and cooperation between leaders of the Soviet Union and the West:

If the West is successfully to resist Soviet expansion, it must surmount a further challenge to its wisdom. This is to understand better the changing basis of power in international affairs and the new conditions which govern its effectiveness. Today, power usually derives as much from the quality of our relationship with others, that is to say, the depth of our co-operation with them and the warmth of understanding between leaders, as from the possession of economic or military strength.

Not long after Heath’s speech in Fulton, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher heeded his advice and, beginning in 1984, established a working relationship with Mikhail Gorbachev that prompted her famously to say, “I like Mr. Gorbachev. We can do business together.” Thatcher and Gorbachev, along with President Ronald Reagan, formed a “warmth of understanding” that ultimately pointed the way to the end of the Cold War.

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher was elected to Parliament in 1959, and her first five years as an MP coincided with Churchill’s final five. By March 1996, when Margaret Thatcher visited Fulton, the formidable barrier about which Churchill warned fifty years earlier had come and gone. The Iron Lady helped to lift the Iron Curtain and promote democracy and freedom in the former Soviet bloc. During her premiership, the fulcrum of world affairs tipped, at least metaphorically.

In her Fulton speech, Thatcher looked back, but in true Churchill fashion, she also looked forward, with an ominous warning:

Within the Islamic world, the Soviet collapse undermined the legitimacy of radical secular regimes and gave an impetus to the rise of radical Islam. Radical Islamist movements now constitute a major revolutionary threat, not only to the Saddams and Assads, but also to conservative Arab regimes who are allies of the West. Indeed, they challenge the very idea of Western economic presence. Hence, the random acts of violence designed to drive American companies and tourists out of the Islamic world. In short, my friends, the world remains a very dangerous place. Indeed, one menaced by more unstable and complex threats than a decade ago. But because the risk of total nuclear annihilation has been removed, we in the West have lapsed into an alarming complacency about the risks that remain. We have run down our defenses and relaxed our guard.

Thatcher’s alert went unheard. Five years after her Fulton address, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, jolted the West from its relative slumber.

John Major

In his “Fulton” Speech, which was given in St. Louis after a day trip to the museum and college in 2008, former Prime Minister John Major reiterated and amplified Margaret Thatcher’s remarks. Major’s warning calls on all nations to be vigilant in the post 9/11 world:

Any security danger comes not from large Nation States but from rogue regimes and terror groups—and here the threat is imminent and serious. It is also universal. Every nation has a stake in this. In its different guises, terrorism has hit West and East as New York, London, Madrid, Moscow, Tokyo, and Bali can testify. All bear the scars and the fatalities of terrorist atrocities.

And so the many prime ministers who succeeded Churchill as well as a number of US presidents have continued to speak with grave importance about world issues in the unlikeliest of locales: Fulton, Missouri. The small college in the middle of nowhere described by Truman to Churchill as “a wonderful school in my home state” has indeed fulfilled Churchill’s mission that “the main end of English statecraft” should be “to cultivate good relations with the United States.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.