Finest Hour 192

Prelude to Power: Churchill and the American Presidency before the Second World War

P76F1X . The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors, Versailles, 28th June 1919 1919 230 William Orpen - The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors - Detail 4

December 15, 2021

Finest Hour 192, Second Quarter 2021

Page 08

By David Freeman

David Freeman is editor of Finest Hour.

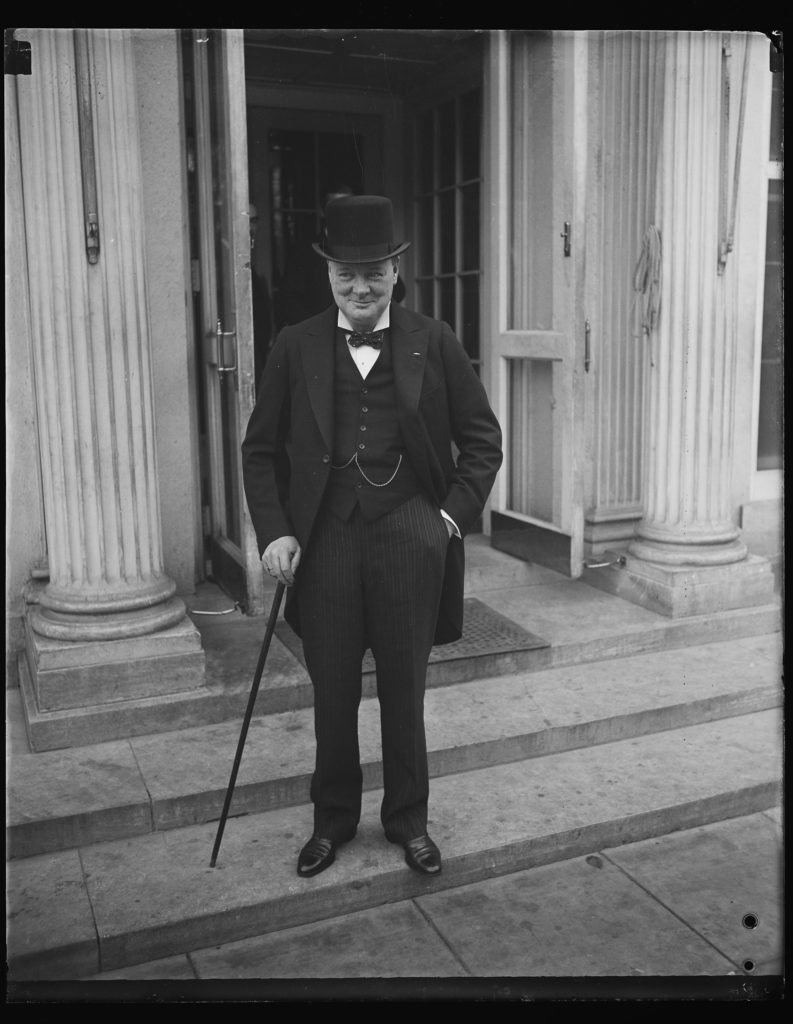

As Prime Minister, Winston Churchill had important working relationships with three different American presidents: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, and Dwight D. Eisenhower. Churchill’s involvement with holders of the Oval Office, however, did not begin or end with this impressive trio.

Altogether, from December 1900 through January 1977, there were eleven occupants of the White House who either met Churchill personally or had at least been in his presence. Additionally, Churchill wrote assessments of several American presidents before his own time, beginning with George Washington. The articles that follow this one describe the encounters that Churchill had with each president from Roosevelt to Gerald R. Ford. This article looks at what came before that, when Churchill studied American history and met several of its leaders but was not yet the leader of his own nation’s government.

Early Giants

In the late 1930s, before the outbreak of the Second World War, Churchill started work on his four-volume History of the English-Speaking Peoples. The third and fourth volumes cover the early history of the United States as an independent nation, and in them Churchill analyzes many US presidents, from the first to hold the office to the first that Churchill himself met.

2024 International Churchill Conference

In The Age of Revolution, Churchill dedicates an entire chapter to “Washington, Adams, and Jefferson,” the first three American presidents. In the same book, he narrates the events of the American War of Independence, but he notes that George Washington’s “services after victory had been won were no less great.” “His firmness and example while first President,” Churchill declares, “restrained the violence of faction and postponed a national schism for sixty years.” Churchill concludes that Washington “filled his office with dignity and inspired his administration with much of his own wisdom.”1

Of John Adams, the nation’s first vice president and Washington’s successor, Churchill writes that he was “a thinker rather than a party politician, an intellectual rather than a leader.” Thomas Jefferson, by contrast, Churchill considers to be “the first political idealist among American statesmen and the real founder of the American democratic tradition.”2

In The Great Democracies, Churchill has much to say about Andrew Jackson, the dominant personality in American politics between the early years of the republic and the Civil War. Churchill asserts that Jackson had “a simple mind, suspicious of his opponents,” that “made him open to influence by more partisan and self-seeking politicians.” In observing that Jackson was somewhat “guided by Martin Van Buren, his Secretary of State” and eventual successor, Churchill goes on to record that Jackson “relied even more heavily for advice on political cronies of his own choosing, who were known as the ‘Kitchen Cabinet,’ because they were not office-holders.”3

Naturally Churchill has the highest regard for Abraham Lincoln. “By his constancy under many varied strains and amid problems to which his training gave him no key,” Lincoln, Churchill writes, “had saved the Union with steel and flame.” “But the death of Lincoln,” Churchill concludes, “deprived the Union of the guiding hand which alone could have solved the problems

of reconstruction and added to the triumph of armies those lasting victories which are gained over the hearts of men.”4

“Worthy, Mediocre Men”

Churchill writes that Lincoln’s hapless successor, Andrew Johnson, “was markedly lacking in political gifts.” The combination of an unpopular incumbent and a bitterly partisan Congress led to the first impeachment trial of an American president and his acquittal by a single vote. “By the narrowest possible margin,” Churchill notes, “a cardinal principal of the American Constitution, that of the separation of powers, was thus preserved.” “Had the impeachment succeeded,” Churchill continues, “the whole course of American constitutional development would have been changed. Power would henceforth have become concentrated solely in the legislative branch of Government, and no President could have been sure of retaining office in the face of an adverse Congressional majority.”5

Following Johnson, Churchill states that “a succession of worthy, mediocre men filled the Presidency….”6 Churchill concludes his survey with the events of the 1890s when Grover Cleveland returned to the presidency following his re-match with Republican rival Benjamin Harrison in 1892. The Panic of ’93 at the start of Cleveland’s second term, however, led to economic turmoil and the tumultuous presidential election of 1896, when William Jennings Bryan electrified the Democratic convention with his “Cross of Gold” speech but also split his party. The first of Bryan’s three unsuccessful presidential bids resulted in the election of the Republican candidate William McKinley. And that is where Churchill’s personal connection to the American presidency begins.

First Presidential Encounters

After first being elected to Parliament in November 1900, Churchill embarked on a lecture tour of North America (see FH 174). Arriving in New York in early December, Churchill travelled to the state capital of Albany, where he met Governor Theodore Roosevelt. At that point, TR was also the Vice President-elect, having been the running mate of President McKinley, whose first vice president had died the year before, leaving the office vacant. Unlike his distant relative Franklin, Teddy Roosevelt never took a liking to Churchill—and no wonder. Their personalities were too similar. There could never be enough oxygen in one room to sustain two such egotists.

From New York, Churchill travelled to Washington, where he was taken to the White House by Senator Chauncy DePew and introduced to President McKinley. This first of many visits, however, was a very brief meeting, and Churchill would not return to the White House for twenty-nine years. In September 1901, President McKinley was assassinated. Vice President Roosevelt succeeded him, but Churchill never met the new president during TR’s time in office.

In May 1910, former President Roosevelt led the US delegation to the funeral of King Edward VII, which Churchill also attended as Home Secretary. On that occasion, TR made a point of not meeting with Churchill. Fortunately for the future of Anglo-American relations, the unprecedented gathering of royalty and rank in London overwhelmed even the outsized personalities of Winston Churchill and Theodore Roosevelt.

The Failed Peacemaker

Churchill never came into contact with William Howard Taft, Roosevelt’s successor, but a historic meeting took place with the man who succeeded Taft. Winston Churchill and President Woodrow Wilson met in Paris on Valentine’s Day, 1919. Love was not in the air. After a long and difficult trip from London to Paris, Churchill—now the British War Minister—attended an emergency meeting at 7 pm in the Quai d’Orsay that had been called by French premier Georges Clemenceau.

The Paris Peace Conference was in full swing. President Wilson was in attendance but preparing to return to the United States the next day. The leaders of the Allied Powers that had achieved victory in the First World War were now at a loss over what to do about the unfolding Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. A meeting between representatives of the Allies, the Bolsheviks, and the anti-Bolsheviks was due to take place, and a policy upon which the Allies could agree was urgently required. Churchill put the case for supporting the anti-Bolshevik cause so as to avert catastrophe. Wilson, however, rejected this idea, concluding that Allied forces already present in Russia “could not be maintained there for ever and the consequences to the Russians could only be deferred.”7 Churchill nevertheless did everything in his power to support the anti-Bolsheviks, but the result was as Wilson had foreseen.

In his memoir The Aftermath, published in 1929—five years after the President’s death—Churchill concluded that Wilson failed to manage well the business of peacemaking abroad because he failed to build bipartisan support for his policies at home. “A tithe of the fine principles and generous sentiments he lavished upon Europe, applied during 1918 to his Republican opponents in the United States [Congressional elections],” Churchill wrote of Wilson, “would have made him in truth a leader of a nation.” Instead, Churchill believed that the President adopted a policy of “Peace and goodwill among all nations abroad but no truck with the Republican Party at home.” “That was his ticket and that was his ruin,” Churchill concluded, “and the ruin of much else as well. It is difficult for a man to do great things if he tries to combine a lambent charity embracing the whole world with the sharper forms of populist party strife.”8

The End of the Beginning

Churchill never met Presidents Warren G. Harding or Calvin Coolidge. Although as a Cabinet minister during the time each man occupied the White House Churchill had to respond to policies set by their administrations, he never travelled to the United States during the time that Harding and Coolidge were in office. This eight-year gap would be followed by a forty-eight year stretch of Presidents who could claim at least some kind of Churchillian encounter.

Churchill returned to Washington, D.C. after an absence of nearly three decades to meet President Herbert Hoover at the White House on 18 October 1929—one week to the day before Black Friday, the Wall Street crash that brought on the Great Depression. Churchill was still an MP, but he had been out of Cabinet office since earlier in the year when his Conservative party had been turned out by Labour. Churchill was introduced to the President by the British Chargé d’Affaires, but the meeting was merely a diplomatic courtesy. Nothing of substance was discussed.9

A second and similar meeting took place between Churchill and Hoover at the White House on 13 February 1932. Churchill had just recovered from being run down by an automobile in the streets of New York the preceding December and was now on the delayed lecture tour that had brought him to the United States. This time Churchill was introduced to the President by the British Ambassador, but the meeting was scheduled for only five minutes before the party had to make way for the German ambassador on a similar mission to introduce a travelling dignitary.

Thus ended Winston Churchill’s early encounters with American Presidents. The great years would not commence until 1941, when the exigencies of war brought together in close partnership the United Kingdom and the United States. At that point, Churchill finally became a White House “regular.”

Endnotes

1. Winston S. Churchill, The Age of Revolution (Norwalk, CT: Easton Press, 1992), p. 308.

2. Ibid., pp. 308 and 315.

3. Winston S. Churchill, The Great Democracies (Norwalk, CT: Easton Press, 1992), p. 119.

4. Ibid., pp. 224–25.

5. Ibid., pp. 261 and 264.

6. Ibid., p. 267.

7. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, Vol. IV, The Stricken World, 1916–1922 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1975), p. 245.

8. Winston S. Churchill, The Aftermath (London: Folio Society, 2007), p. 94.

9. HH Calendar 1929–10–18, Herbert Hoover Presidential Library, West Branch, IA.

10. HH Calendar 1932–02–13, Hoover Library.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.