Finest Hour 188

Stanley Baldwin and Winston Churchill

Stanley Baldwin

January 2, 2021

Finest Hour 188, Second Quarter 2020

Page 22

By Philip Williamson

Philip Williamson is professor of History at Durham University and author of Stanley Baldwin: Conservative Leadership and National Values (1999) and co-editor (with Edward Baldwin) of The Baldwin Papers. A Conservative Statesman 1908–1947 (2004).

Stanley Baldwin (1867–1947) was one of the most successful and important political leaders of twentieth-century Britain. In October 1935, Winston Churchill described him as “a statesman who has gathered to himself a greater volume of confidence and goodwill than any other man I recollect in my long political career”—and Churchill had been familiar with the greatest figures in British public life during the previous forty years. When Baldwin retired in 1937, he was in Churchill’s words “loaded with honours and enshrined in public esteem,”1 receiving tributes not just from members of his Conservative party and its partners in the National coalition government, but also from leading figures in the Labour and Liberal opposition parties. Yet his reputation declined precipitously after the outbreak of the Second World War. For various periods Baldwin and Churchill had been colleagues and opponents: Baldwin revived Churchill’s political career in 1924, but at other times he had a large part in excluding him from government office. They differed on many of the great issues of the 1930s, and Churchill’s later memoirs for these years, The Gathering Storm, entrenched a persistently harsh historical verdict on Baldwin’s leadership.

Party Leader and Prime Minister

Baldwin was Conservative party leader for fourteen years, from 1923 to 1937, and prime minister three times: 1923–24, 1924–29, and again—after four years from 1931 as deputy prime minister in the National government—from 1935 to 1937. Impressive as this career at the top of British politics was in duration, his greater significance is as a dominating political figure during the beginnings of modern British politics and a long pattern of Conservative party success. Baldwin was the first long-serving Conservative leader within full British parliamentary democracy, after universal suffrage—the right to vote for women as well as all men—was established in legislation in 1918 and 1928, creating an overwhelmingly working-class electorate.

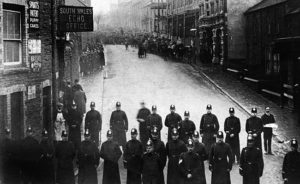

Baldwin made his reputation by helping to free the Conservative party from a coalition government in 1922, yet led it into another and more enduring coalition government in 1931. He was the first Conservative prime minister to feature in the modern mass media of radio and sound film. He was the first to bear the political effects of chronic economic depression and mass unemployment, and to face a major socialist party linked with a powerful and highly politicised trade-union movement. He became the first leader of the opposition to a Labour government, and the only prime minister to be faced with a general strike.

During Baldwin’s party leadership, the British overseas dominions moved from Empire to Commonwealth, and India towards central self-government, the last great struggles between free trade and protection were fought, and sterling suffered its first and greatest devaluation. Baldwin was also the first Conservative leader to face the challenge of Stalinist and fascist ideologies, and to justify military rearmament to an electorate attached to disarmament and international peace-keeping, and fearful of provoking aerial bombing of towns and cities. He remains the only prime minister to have overseen the abdication of a British monarch.

In such difficult conditions for a party identified with hierarchy, property, privilege, monarchy, sound finance, and imperialism, Baldwin’s resilience and success were remarkable. He led the Conservative party to three of the largest general election victories of modern times, in 1924 and—as a coalition partner—in 1931 and 1935. From a succession of intense political problems—the General Strike in 1926; confrontations with the owners of the chief popular newspapers, Rothermere and Beaverbrook, in 1930–1; the financial and political crises in 1931; and the crisis over King Edward VIII’s intended marriage in 1936—he emerged with enormous public authority. Yet as prime minister he also suffered defeat after two general elections, in 1923—when he brought defeat upon his government by calling a very early election on the deeply divisive issue of trade protection—and in 1929. The first defeat nearly forced his resignation, and contemporaries as well as later biographers and historians were frequently puzzled by an apparent unevenness in his judgement and control of political business. There were prolonged rebellions against his leadership over trade policy from 1929 to 1931, and over constitutional reform for India— with Churchill as a prominent opponent—from 1930 to 1935, while his defence of the National government’s foreign and armament policies from 1933 to 1937 also provoked Conservative divisions, often (though not always) with Churchill as a leading critic.

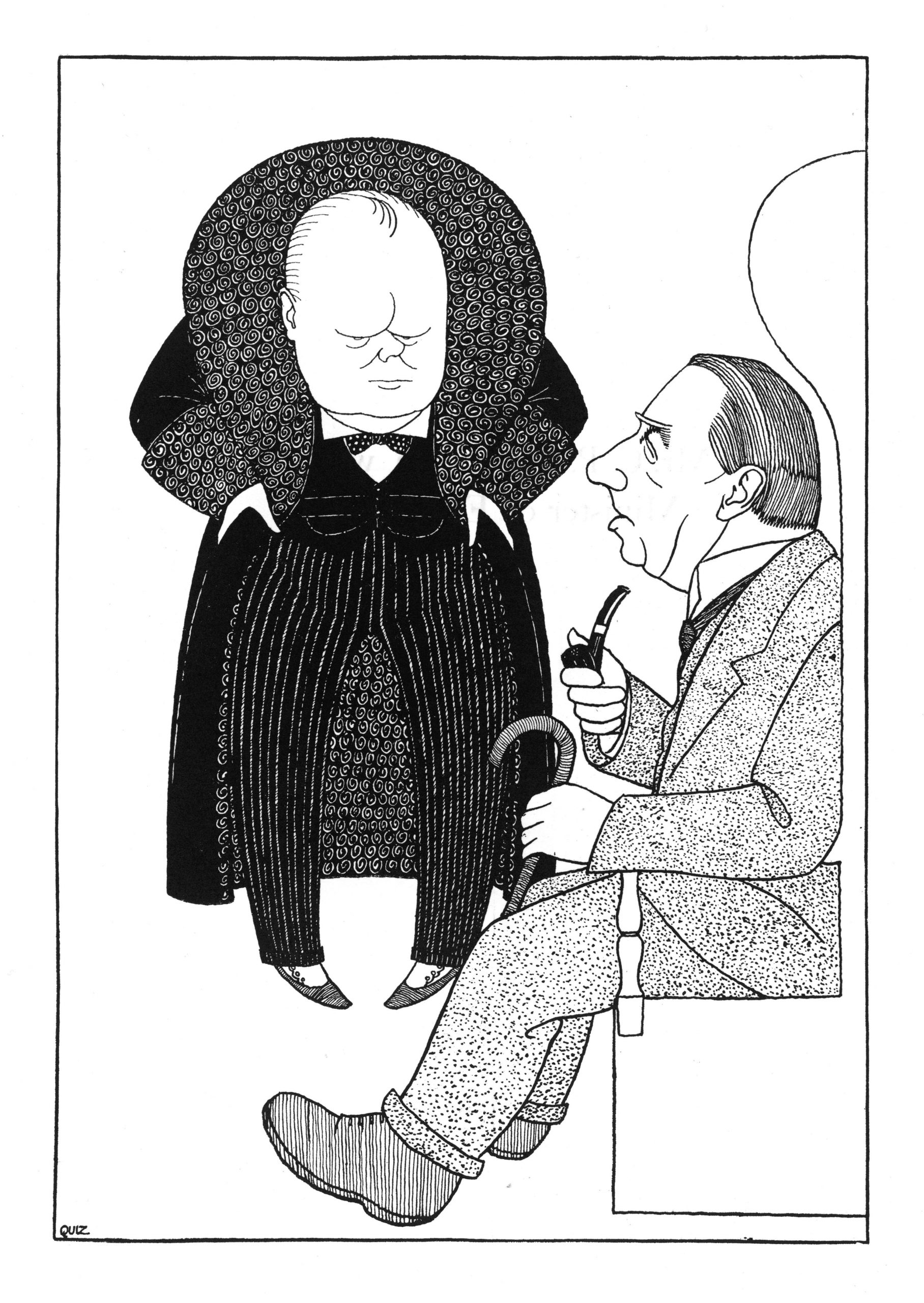

Contrasting Styles

Baldwin is not an easy politician to understand. In part this is because he left fewer private records than political leaders of similar stature. Churchill habitually conducted much of his political business by lengthy letters and memoranda, large numbers of which are preserved in government records and the papers of his colleagues. He was also very conscious of his future place in history and kept a huge personal archive, which he used to write extensive and well-documented books, described by A. J. Balfour as autobiography disguised as history. In contrast, Baldwin worked largely by discussion and meetings, and wrote few (and then only short) political letters, and barely any memoranda. His surviving papers consist chiefly of office files gathered by his secretaries. He did not write memoirs, observing that “no man can write the truth about himself.” Only with great reluctance was he persuaded to co-operate with a biographer selected by his friends (G. M. Young, who turned out to be a disastrous choice), believing that “only fifty years hence could the real value of his or any other Premiership be judged”—with the effect of enabling his critics to monopolise the judgements, and to burden his reputation with what can only be described as historical myths.2

There was a contrast also in political purposes and style; Baldwin and Churchill were quite different types of Conservative politician. Churchill had been a soldier, a journalist, and an adventurer, and he regarded political leadership as a career and a theatre of ambition. After beginning as a Conservative, he spent twenty years as a Liberal MP and government minister, leading several of the great and most absorbing offices of state, responsible for fleets, armies, and much of the empire. He relished action, drama, big tasks, and large effects, and even when he returned to the Conservative party he retained radical political instincts. He wanted challenges, confrontations, new issues, decisions, and public renown, and could seem impulsive, inconsistent, and unsteady in judgement.

Baldwin had been an iron and steel manufacturer, a bank and railway director, and a quiet backbench MP. He was always a Conservative, but in a distinctive way: a paternalist employer, a county and country man, with artistic and literary interests and family connections, most notably with Rudyard Kipling, his cousin. For him, political life and government office were matters more of duty than ambition. He was modest, thoughtful, and cautious, and sensitive to the values of continuity and conciliation. Apart from his attempt to introduce tariff protection in 1923, he initiated no great act of state and rarely took a commanding part in policy making or legislation. His achievements lay elsewhere, in the management of political opinions and public attitudes.

Baldwin and Churchill were both impressive public speakers, but while speeches for Churchill were a type of action, for Baldwin they were a form of education. Politics for Baldwin were primarily concerned with perceptions and belief. In his view, the social, economic, and political transformations unleashed by the First World War had produced a crisis in values, made still more dangerous by the creation of a mass democracy, containing many politically naïve new voters liable to be misled by wild promises of irresponsible demagogues and by the emergence of a strong Labour party committed to socialism.

Baldwin’s fundamental aim was stabilisation, to prevent social, imperial, and international dislocations, while accepting pragmatic concessions and recognising that sensible changes could be improvements. Applying his considerable experience in business, he gave much attention to the management of cabinets, committees, and colleagues, while expecting departmental ministers to take full responsibility for their own areas of policy, in similar fashion to the now much-admired style of Clement Attlee as prime minister in the Labour government of 1945–51. But Baldwin’s most effective political method was speechmaking, not just in parliament and to party and election meetings, but to many non-political audiences and on the new media of radio and newsreels.

In 1948 Churchill described Baldwin as “the greatest party manager the Conservatives have ever had,” but Baldwin’s main aims were always wider and deeper.3 One of his chief concerns was to “educate” the Conservative party, to ensure that it accepted the realities of mass democracy and was not dominated by its members’ own self-interest and narrow opinions. One duty of responsible and far-sighted Conservative leaders was to resist the prejudices of party activists and conservative newspapers, whether over tax cuts, government spending, trade unions, or trade and imperial policies—which largely explains the complaints and rebellions against Baldwin by party members.

Baldwin believed that if Conservatives were to succeed, whether in resisting socialism or in winning elections, they had to display sensitivity and sympathy towards all sections of the national community. They should show that they cared as much as the Labour party and trade unions about social hardship; they should not just attack socialism, but recognise that the Labour movement expressed an attractive idealism that could be defeated only with alternative Conservative ideals. These consisted especially of the ethic of public service, and of appeals to solidarities other than those of class interest: to the local communities of city, town, and county (though his historical presentation as a bucolic English countryman is a caricature), to the values of family and home, and to national culture, constitutionalism, and Christian faith. Nor should Conservatives be unremittingly hostile towards the trade unions and the Labour party. Although Baldwin sometimes criticised these as fiercely as other Conservatives, most notably during the General Strike, he more commonly treated them with respect, good humour, even friendliness, for example appealing eloquently for industrial peace. For him, the best way to frustrate the Labour movement was not by constant obstruction, which might easily encourage its extremists, but by keeping its moderate leaders involved in debate, negotiation, and parliamentary procedures. He would never have been so inept as to attack former Labour colleagues as aiming to create a “Gestapo,” as Churchill did during the 1945 election campaign.

Baldwin was also acutely aware, more so than most political contemporaries, of further and more decisive bodies of opinion— Liberal, moderate, politically uncommitted, and “un-political.” To these he appealed particularly through many non-political addresses in which he spoke as a public moralist: to schools, universities, religious assemblies, chambers of commerce, and professional, scientific, literary, artistic, philanthropic, and civic associations, and in BBC radio talks on cultural themes or public occasions. His embrace of democratic principles, his appeals to the best standards in public life, and his presentation of an inclusive, moderate Conservative idealism did much to reduce political tensions, to broaden the Conservative party’s appeal, and to assist its electoral success. All this also helped to undermine popular support for the Liberal party and to persuade many Liberals—including Churchill in 1924—to join the Conservative party.

Rearmament: Politics & Myth

Baldwin’s and Churchill’s political careers were interlinked during the interwar years, and so, in one particular respect, were their historical reputations. Baldwin’s large part in ending the Lloyd George coalition government in 1922 contributed to an abrupt halt to Churchill’s career as a Liberal cabinet minister and his temporary loss of a parliamentary seat, leaving him scrambling to find a new position in national politics, given that a divided and weakened Liberal party offered poor prospects for soaring ambitions. Baldwin’s decisions in 1924 to support his return to parliament as an anti-socialist “constitutionalist” and then to appoint him as chancellor of the exchequer—part of Baldwin’s efforts to weaken the Liberals still further— restored him to prominence. But Churchill was increasingly embarrassed as a Conservative turn towards trade protection clashed with his own long commitment to free trade—which he could not easily abandon without further damaging charges of inconsistency—and after the defeat of Baldwin’s government in 1929, he again became politically isolated.

Churchill’s decision to adopt a new political course by resisting further constitutional reform in India in alliance with the Conservative “die-hard” right made him into a leading critic of Baldwin and other Conservative leaders, but failed either to change party policy or to overturn these leaders. It also ensured his exclusion from the National government. Churchill’s public defence of Edward VIII during Baldwin’s skilful management of the public delicacies of the abdication crisis—an intervention which Churchill later admitted had been badly misjudged—made it still more difficult for him to regain government office. But it was over British military defence and rearmament that Baldwin and Churchill came to differ most, though much more in retrospect than in contemporary politics.

From 1933 Baldwin persistently warned of the dangers from fascist dictatorships. From July 1934, against a great weight of peace opinion and Labour and Liberal opposition, he justified the successive rearmament programmes of the National government, and during the 1935 election campaign declared that he could not continue as prime minister unless he obtained a mandate to strengthen the armed forces still further.4 The aim of these programmes was to deter Hitler from beginning a war. But during 1935 Baldwin, in rebutting the British peace slogan that “great armaments lead inevitably to war,” stated that there would be “no great armaments”; and in November 1936 he commented hypothetically that if an election had been held in 1933 or 1934 in defence of the current large-scale rearmament, it might have led to defeat. His point was that the government had succeeded in changing public opinion, persuading much of the electorate to accept rearmament. Churchill had criticised the government for being slow to rearm, but in 1935 he described the government’s new rearmament measures as “a most formidable and tremendous advance in British defence” and in November 1936 he stated that Baldwin had “fought and largely won” the general election on rearmament.5

From the perspective of a much-increased German threat two years later, however, Churchill became more critical of the government’s record, and began a historical revision, which emphasised the correctness of his own warnings against Nazi Germany. In selected speeches on defence and foreign policies edited by his son, passages from Baldwin’s November 1936 speech were truncated to give an impression that he had not called for rearmament in 1935, and Churchill’s statement in the same debate that Baldwin had “fought and largely won” the election on rearmament was silently omitted.6

During the Second World War, assertions that Baldwin had “failed to rearm” and had “deceived the election” were taken up by Labour and Liberal critics as part of a general disparagement of the National government’s policies, and became a matter of common belief. In The Gathering Storm, Churchill turned these claims into what came to be regarded as authoritative history, summarised by his indexer as Baldwin “denies” the need for rearmament and “confesses putting party before country.”7 The tragic reality was that all British political leaders who argued for rearmament in the form of RAF bombers—Churchill as well as Baldwin—did so on what turned out to be false expectations: that Hitler would be deterred by the threat of bomber aircraft, and that the French army could halt a German attack.

In one important respect, Churchill may have learned from Baldwin. Churchill’s criticisms of Hitler’s Germany were for much of the 1930s expressed largely in terms of relative military strengths, the balance of power, and British security. In contrast, Baldwin’s speeches mounted an impressive ideological, moral, and spiritual opposition to Nazism, seeking to overcome the considerable public resistance to rearmament by appealing to the defence of freedom, individualism, democracy, constitutional government, and Christian values. From 1938, as war became likely and then a reality, Churchill began, famously, to adopt similar terms. In this respect, Churchill in 1940, speaking of the defence of Christian civilisation, was close to Baldwin in 1935.8

Endnotes

1. Churchill at the 1935 Conservative party conference, The Times, 4 October 1935, p. 8; Winston S. Churchill, The Gathering Storm (London: Cassell, 1948), p. 18.

2. See Philip Williamson, “Baldwin’s Reputation: Politics and History, 1937–1967,” Historical Journal, 47 (2004), pp. 127–68.

3. Churchill, Gathering Storm, p. 30.

4. The fullest and best account remains Keith Middlemas and John Barnes, Baldwin (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1969), chs. 27–33.

5. House of Commons Debates, 302, c. 423 (22 May 1935).

6. Winston S. Churchill, Arms and the Covenant, ed. Randolph Churchill (London: Harrap, 1938), pp. 375–76, 385–86, and compare with the original passages in House of Commons Debates, 317, cc. 1103–4, 1144 (12 Nov. 1936). The doctored version of Baldwin’s speech was still being used forty years later in Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, vol. V, The Prophet of Truth, 1922–1939 (London: Heinemann, 1976), pp. 797–98.

7. Churchill, Gathering Storm, p. 697, and see Williamson, “Baldwin’s Reputation,” pp. 141–45.

8. Philip Williamson, “Christian Conservatives and the Totalitarian Challenge, 1933–40,” English Historical Review, 115 (2000), pp. 607–42.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.