Finest Hour 188

Twin Titans

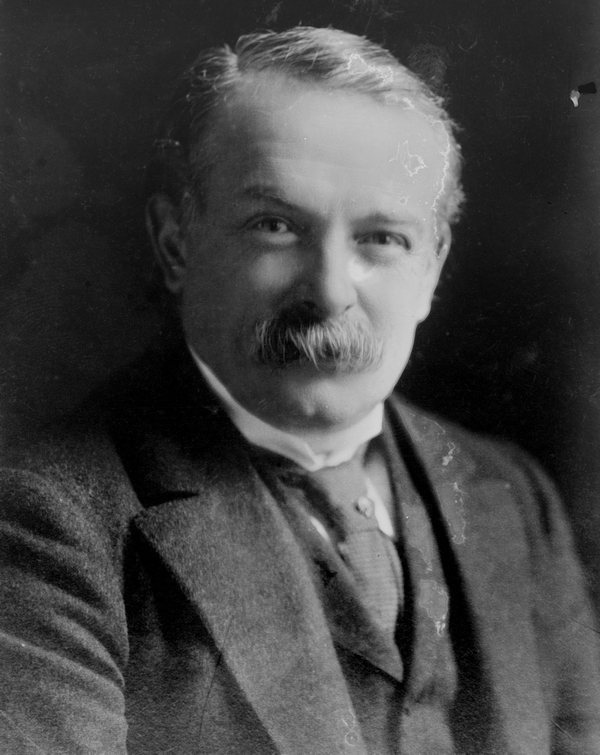

David Lloyd George

September 1, 2020

Finest Hour 188, Second Quarter 2020

Page 18

By Kenneth O. Morgan

Kenneth O. Morgan is author of books about Lloyd George, James Callaghan, and Michael Foot. He serves in the House of Lords as Baron Morgan of Aberdyfi.

During his years in the Liberal party from 1904 to 1923, Winston Churchill served under three prime ministers. The third of these was unique. For unlike his relationships with Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman and H. H. Asquith, towards David Lloyd George, Churchill was almost in awe. Robert Boothby, who served as Churchill’s Parliamentary Private Secretary when Churchill was Chancellor of the Exchequer, told a famous story in his memoirs about a meeting between the two great war leaders that took place in the 1920s. The old relationship, Churchill told Boothby ruefully, was quickly restored, “the relationship between Master and Servant. And I was the Servant.”1

Of course, Lloyd George was eleven years older than Churchill. He entered parliament in 1890, while Churchill was still a schoolboy at Harrow, and was first appointed to the Cabinet two and a half years before Churchill. But the ascendancy was personal and psychological as well as political. Even though Lloyd George had been a fierce critic of the South African War while Churchill was an imperialist, when the latter crossed the floor to join the Liberals in 1904, he chose to sit next to the Welshman in the Commons, after a controversial maiden speech, and they joined in onslaughts on the failing Unionist government. Churchill had nothing to do with Lloyd George’s ventures in politics on Welsh and other matters down to 1906 and was first appointed to the Colonial Office as a junior minister while his colleague went to the Board of Trade (with Churchill the more zealous free trader of the two). But after 1908 the pair formed a bold and dynamic partnership as pioneers of social reform. Churchill went down to the Criccieth home of Lloyd George, who was now Chancellor, to plan out a vast prospectus of social insurance, following up his colleague’s visit to examine the insurance system in post-Bismarck Germany. The outcome was a double triumph, Lloyd George brilliantly carrying through the 1911 National Health Insurance Act, and Churchill starting up labour exchanges to tackle unemployment before advancing to the Home Office.

They worked shoulder to shoulder down to the war in 1914, fighting for Lloyd George’s “People’s Budget” of 1909 (even though Churchill, a cousin of the Duke of Marlborough born in Blenheim Palace, was less enthusiastic for the land taxes imposed by a Welsh colleague, brought up in a shoemaker’s cottage in a rural Welsh hamlet.) Churchill, however, became president of the Liberals’ Budget League. When Lloyd George was accused of serious corruption in the 1912 Marconi shares’ case, Churchill backed him aggressively in a highly partisan manner. The only major disagreement between them was over Churchill’s increased naval estimates of £51 million in 1914. On this occasion, Asquith supported Churchill, and the Chancellor had to climb down. But after that, there was broad harmony between them again, and they collaborated in the summer of 1914 in trying to avert civil war in Northern Ireland.

2025 International Churchill Conference

It was the outbreak of world war that finally brought them close together. At first it seemed to lead to the opposite. While both favoured a more peripheral strategy in Europe instead of the bloody slaughter in the trenches of France, Churchill was the political casualty after the disastrous losses of the Dardanelles campaign.

Churchill was the prime victim in the political crisis of May 1915, which ended the Asquith Liberal government. By the end of the year, facing much Unionist criticism, he had left the government. Lloyd George, on the other hand, made giant strides, making a great success of the novel field of the Ministry of Munitions, followed by promotion to being Secretary for War after the death of Lord Kitchener in July 1916. After a series of manoeuvres in which Churchill played no part, Lloyd George emerged in a political coup on 7 December 1916 as prime minister of an all-party coalition in place of the ageing Asquith, in alliance with the Unionists and their leader, Andrew Bonar Law. Churchill meanwhile was a distrusted marginal figure, left out of the new government, spending time in the army in France and resentful of the disloyalty of his colleagues. Lloyd George, after all, had initially given his support to the Dardanelles invasion, but casually allowed Churchill to take all the blame, even though his friend had backed him faithfully during the Marconi scandal, which might well have ended his career. Their relationship was often at a low ebb.

But it was the new premiership that restored their comradeship. It rescued Churchill’s career. In May 1917, with fighting on the Western Front at a critical stage, Lloyd George felt strong enough to boost his Unionist-dominated government with an input of two important Liberals: Edwin Montagu at the India Office and his old ally Churchill at the Munitions Ministry in place of Lloyd George’s loyal lieutenant Christopher Addison. From that time onwards, the Lloyd George– Churchill partnership was a pivot of the government—after all, neither of the pair was a blinkered partisan and each warmed to the idea of coalition government. Churchill’s career, seemingly shattered by the Dardanelles, was now reborn. He proved a vigorous, successful minister at Munitions and in particular had a less troublesome time with the trade unions than Addison had done in 1916–17. His later reputation as an enemy of the trade unions and fierce opponent of their leftwing ideology was not apparent at this stage. Ironically, Lloyd George turned him into a leading exponent of “war socialism.”

Churchill took careful note of Lloyd George’s methods as prime minister, which made a profound impact upon Churchill’s own leadership during the Second World War. He approved of Lloyd George’s attempt to detach himself from the details of central strategy with a War Cabinet, though Churchill himself was careful to confine himself to key departmental ministers being in the central command rather than Lloyd George’s penchant for non-partisan outsiders, businessmen, and others. Nor was Churchill to create a body of special advisers such as Lloyd George set up, the so-called “garden suburb” working in temporary huts in the garden of No. 10. On the other hand, he made particular use of Lloyd George’s invention of a central Cabinet Secretariat, headed by Sir Maurice Hankey, supported by his fellow Welshman Thomas Jones. Both prime ministers saw it as an essential instrument in avoiding the dilatory style of Asquith’s methods of wartime government and making sure that the prime minister had clear knowledge of what was expected from his ministers and overriding authority to ensure that the will of No. 10 would prevail.

Churchill made sure that he did not face Lloyd George’s problems of being a prime minister without a party by ensuring that he was elected leader of the Conservative Party in November 1940. Churchill also absorbed the lessons of Lloyd George’s problems with the leading generals in 1916–18 after the bloodbath at Passchendaele, when politically-minded military leaders like Haig and Robertson directly challenged his authority and opposed the prime minister’s attempts to create unity of command, finally decided by supremacy going to the Frenchman Marshal Foch. Lloyd George also provided a crucial personal contribution to victory on the high seas by protecting merchant vessels through creating the convoy systems and thereby safeguarding food supplies. Churchill also admired Lloyd George’s genius as communicator in maintaining national morale and inflicting unconditional surrender upon the German enemy. It can fairly be said that in the first war Lloyd George’s personal contribution to victory, including his alliance with the French and Americans, was quite as overwhelming as Churchill’s in the second.

Churchill was now manifestly Lloyd George’s man. He was classified as a Coalition Liberal in political manoeuvres to ensure the continuation of the coalition between Lloyd George and Bonar Law at the end of the war. In the so-called “coupon” general election of December 1918, Churchill was a vigorous participant in the break-up and division of his party in which the coalition won a huge majority amidst a widespread air of post-war jingoism. Lloyd George promoted Churchill to hold the highly appropriate post of Colonial Secretary, to consolidate a new imperial domain in the Middle East, with British-run mandates in Palestine and Transjordan and control over oil-rich Mesopotamia. Churchill was the belligerent voice of empire as never before, though he fortunately had an opportunity to show a more liberal side in denouncing the disaster wrought by General Dyer in India with the massacre of hundreds of unarmed Sikhs in Amritsar.

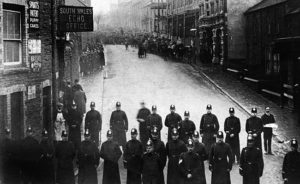

Churchill was always his own man and a highly opinionated minister, quick to criticise his prime minister’s policies. This was less evident in domestic policy, where he and Addison joined in trying to push the Government in favour of “New Liberal” social reform. He warmly supported Addison’s new publicly financed housing programme and attack on city slums. He urged the government in their financial policies to “budget for hope not for despair.”2 This was in spite of his hostility towards organised labour, major trade union strikes, and attempts to form a Triple Alliance of workers threatening a general strike. This, declared Churchill, showed that labour was “unfit to govern.”3 He became deeply unpopular in working-class communities, notably the South Wales miners, for the remainder of his career. He and Addison spoke on behalf of a “fusion” of Coalition Liberals and the Unionists in 1920—but Addison wanted it to promote humanitarian reform, Churchill to fight the nascent Labour Party. In fact, nothing happened, and the Lloyd George coalition limped on.

One area where Churchill was an important backer of Lloyd George was in Irish policy after the war. Churchill had never been an extreme opponent of Irish Home Rulers. As a historian, he sympathized with many of their past grievances and the idea of “the union of Irish hearts.”4 Nevertheless, he did back Lloyd George in using the auxiliary “Black and Tans” in the policy of “retaliation,” with virtual war between the British Army and Irish Republican Army, along with their political arm, Sinn Fein in 1920–21. Churchill also strongly supported Lloyd George in his reversal of policy and the beginning of peace talks in August 1921. Churchill was an important figure in the peace negotiations with Sinn Fein and played a major part in such technicalities as the Oath of Allegiance. Next to Lloyd George, he played a leading part in the partition of Ireland, which brought an end to major hostilities.

An area, however, where Churchill and his prime minister were often at odds was in foreign affairs. Lloyd George’s mind was focussed on reaching an understanding with the two pariah nations after the war, Germany and Russia. He was anxious to move on from the unsatisfactory peace treaty at Versailles and to revise that and the other treaties. This especially applied to policy towards the new Bolshevik regime in Russia. Churchill was passionate, almost unbalanced, in his ferocity towards the Soviet regime, and to “grasping the hairy paw of the baboon.”5 The prime minister had determined early on that British troops, sent to Russia to aid the White Russian anti-Czarist forces, should be brought home; Churchill insisted that they be heavily reinforced. In the end, Lloyd George had to rebuke him by letter and in open Cabinet: “I have found your mind so obsessed by Russia.”6 The Prime Minister won his point, and another slaughter of British troops in Europe was averted. Lloyd George had British troops withdrawn from Russia by the end of 1919, and a trade treaty was concluded with the new Soviet regime, along with de facto recognition. The beginnings of a realistic relationship with Russia and access to its markets for British goods were established.

By contrast, Churchill did endorse most of Lloyd George’s attempts at reconciliation with post-imperial Germany. Though he played no direct part in the Treaty of Versailles, Churchill criticised French revanchist policies followed by Clemenceau, the French prime minister, and his successor Poincaré, a Lorrainer. Churchill thought the scale of reparations imposed on the defeated Germans “malignant and silly.”7 So were some of the new frontier arrangements involving German minorities. Unlike Churchill, however, Lloyd George particularly objected to the creation of Czechoslovakia, whose president (“that little swine Benes”) he particularly distrusted.8 He and Churchill were to take sharply different views at the time of Munich in 1938. Churchill did, however, recall one crucial lesson from post-1918 British foreign policy, the need to retain American involvement in post-war reconciliation. He pursued this aim at the end of the Second World War, though it was Clement Attlee and Ermest Bevin who ensured that the US would not again lapse into isolationism, as it had so disastrously done after 1918. The United Nations was thus far more robust than the League of Nations had ever been.

In October 1922, Lloyd George fell from power after the Unionists objected to his bellicose policy towards Turkey, which Churchill generally supported. Thereafter his close relationship with the Welshman, still a very important one, became more episodic. Churchill predictably joined the Conservatives in 1924 and served for five unhappy years at the Treasury. Lloyd George now devoted himself to Keynesian-type, pump-priming proposals to combat mass unemployment and industrial stagnation: Churchill had scant sympathy with them, and mechanically repeated the Treasury orthodoxy. They did come together more in the thirties over foreign affairs, and also on some lesser issues. Both men showed sympathy for the quasi-fascist Edward VIII in his abdication in 1936. Churchill sympathised with Franco in the Spanish Civil War; Lloyd George, the lifelong democrat, backed the Republicans.

Towards Germany there was an important difference. Churchill was relentless in his opposition to Hitler’s territorial aggression in Germany. Lloyd George tended to favour a non-aggression pact, gave backing to a German “peace offer” in 1935, and questioned the pact to guarantee Poland. He paid a disastrous visit to meet Hitler in Berchtesgaden. He helped to make Churchill prime minister in 1940, but his later defeatist comments led Churchill to compare him with the aged Pétain in France as an appeaser. There was a final episode in late 1940 when Churchill, perhaps reluctantly, offered appointments to Lloyd George, including the role of ambassador in Washington. To the relief of Roosevelt, alarmed at Lloyd George’s apparent admiration for Hitler, this fell through. Winston and David, long-term comrades in arms, were both rivals as well as partners, and it would not have worked. This was Churchill’s war. It was “Master and Servant” no longer.

Yet the two men remained remarkably close over five tumultuous decades, the two outstanding prime ministers of the century whose statues bestride Parliament Square and flank the entrance to the House of Commons. Lloyd George’s role as architect of the welfare state gave him primacy in domestic policies, and he largely settled the Irish question. Churchill was badly wrong on India and the gold standard, but his historic war leadership during the “darkest hour” was incomparable. Both were majestic parliamentarians, Lloyd George mesmerizing the Commons, Churchill orating to History. The Oxford historian A. J. P. Taylor was often an acerbic or satirical critic. Yet, for him, Churchill was “the saviour of his people,” Lloyd George “the greatest ruler of England [sic] since Oliver Cromwell.”9 These judgements still stand.

Endnotes

1. Robert Boothby, Recollections of a Rebel (London: Hutchinson, 1978), pp. 51–52.

2. Churchill to Lloyd George, 22 April 1922, Lloyd-George Papers, F/20/2/63, House of Lords Record Office, London.

3. The Times, 23 February 1920.

4. Lloyd George to Churchill, 22 September 1919, Lloyd-George Papers, F/9/1/2.

5. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, vol. IV, The Stricken World, 1917–22 (London: Heinemann, 1975), p. 400.

6. Gordon A. Craig, “Churchill and Germany,” in Robert Blake and William Roger Louis, eds., Churchill (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 30.

7. Paul Bew, Churchill and Ireland (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 167.

8. A. J. Sylvester, Life with Lloyd George (London: Macmillan, 1975), p. 219.

9. A. J. P. Taylor, English History 1914–1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1965), p. 4n.; and in foreword to Kenneth O. Morgan, Lloyd George (London: 1973), p. 8.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.