Finest Hour 188

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – The Lion’s Roar

August 5, 2020

Finest Hour 188, Second Quarter 2020

Page 44

Review by Chris Matthews

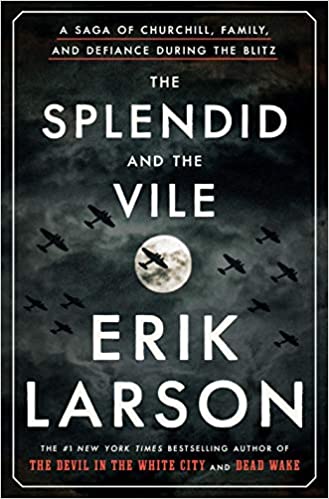

Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family and Defiance during the Blitz, Crown, 2020, 585 pages, $32. ISBN 978–0385348713

Chris Matthews hosted Hardball on MSNBC for twenty years and is a member of the Board of Advisers to the International Churchill Society.

Erik Larson tells the story of London under the Blitz with all its sound and fury, but also its unexpected joy. The Splendid and the Vile delivers the great saga with a novelist’s touch. It is like you are watching and hearing the days and nights of 1940 as a passenger on a London double-decker bus.

“It was the dust that many Londoners remembered as being one of the most striking phenomena of this attack and others that followed,” Larson writes. “As buildings erupted, thunderheads of pulverized brick, stone, plaster, and mortar billowed from eaves and attics, roofs and chimneys, hearths and furnaces—dust from the age of Cromwell, Dickens, and Victoria.” Through that dust we meet up with our defiant hero.

2024 International Churchill Conference

“Good old Winnie,” comes a voice from the crowd. “We thought you’d come and see us. We can take it. Give it back. When are we going to bomb Berlin, Winnie?” Now we hear the answer that would make all the difference: “You leave that to me.”

This was the Churchillian battle cry that roused the British heart during the Blitz: “You leave that to me!”

Churchill knew his people because he knew himself. He knew the British people wanted most of all to feel like they were fighting back. When the military silenced the few anti-aircraft guns defending London in order to save ammunition, the prime minister saw the larger picture that the bean counters missed.

“On Churchill’s orders, more guns were brought to the city, boosting the total to nearly two hundred, from ninety-two,” Larson writes. “More importantly, Churchill now directed their crews to fire with abandon, despite his knowing full well that guns only rarely brought down aircraft.”

Even if the bullets did not bring down a single Luftwaffe plane, the prime minister knew how good it made his countrymen feel to hear the racket. “The impact on civic morale was striking and immediate.” The nightly firing of those anti-aircraft guns created “a momentous sound that sent a chattering, smashing, blinding thrill through the London heart.” The British people were hitting back: “Searchlights swept the sky. Shells burst over Trafalgar Square and Westminster like fireworks sending a steady rain of shrapnel onto the streets below, much to the delight of London’s residents.”

Watching and hearing it all from the roof of 10 Downing Street was the man who gave that delightful order to fire at will. Here is how his private secretary, “Jock” Colville, described that scene in the late summer of 1940:

The night was cloudless and starry, with the moon rising over Westminster. Nothing could have been more beautiful and the searchlights interlaced at certain points on the horizon, the star-like flashes in the sky where shells were bursting, the light of distant fires, all added to the scene. It was magnificent and terrible…. Never was there such a contrast of natural splendour and human vileness.

Larson best captures that odd “splendour” aroused by the Blitz in the sensuous account of a young woman diarist. She described her surprise at how she felt while lying in bed after a near miss by a German bomb:

“I lay there feeling indescribably happy and triumphant. ‘I’ve been bombed!’ I kept saying to myself over and over—trying the phrase on like, like a new dress, to see how it fitted. ‘I’ve been bombed! I’ve been bombed—me!’ Never in m my whole life have I experienced such pure and flawless happiness.”

Larson’s book is built with such first-hand accounts and the lessons they draw. One lesson I picked up in The Splendid and the Vile dealt with the latter part of its title. It was how much the battle to bring Britain to its knees owes to Adolf Hitler’s “vile” assumption about mass psychology.

Hitler could not understand why the British would not quit. Just as his adversary Churchill knew how to elevate the human spirit, the Führer thought he knew how to bring it down. He truly wanted Britain to be his junior ally in world domination and thought he could win it over by calculated intimidation.

One lesson of Larson’s book for me was how much Hitler wanted to avoid a direct air attack on London. He had two reasons. One, he feared what the RAF would do to the grand buildings that he and Albert Speer had put up in Berlin; and two, he continued to see Britain as a potential ally.

As Larson writes, “Hitler was serious about seeking an agreement with Britain that would end the war, though he grew convinced that no such thing could be achieved while Churchill was still in power.” Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring even warned his commanders that any who let their bombs drop on London would be transferred “to the infantry.”

In August of 1940, Hitler continued to believe Britain would buckle. He was planning a great spectacle in his capital to celebrate what he saw as the imminent end of the war in Europe. “In Berlin,” Larson writes, “workers continued building grandstands in Pariser Platz, in the center of the city, to prepare for the victory parade that would mark the end of the war. Hitler wanted the stands ready by the end of the month.”

The victory never came. Nor did the British ever have to issue the dire code word “Cromwell,” signaling that the much-touted German invasion was underway.

“Joseph Goebbels grew perplexed. None of it made sense,” Larson notes deep into his story. Hitler’s propaganda minister could not fathom why Churchill had not yet conceded defeat, given the nightly pounding of London: “Why was London still standing, Churchill still in power?”

One essential reason is what Larson calls Churchill’s “naked confidence that under his leadership Britain would win the war.” It was his “striking trait: his knack for making people feel loftier, stronger, and above all, more courageous.”

One way he did it, as we learn here, was that nightly, joyous crackle of those extra anti-aircraft guns.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.