Finest Hour 187

Books, Arts & Curiosities – The Hollow Men

April 4, 2020

Finest Hour 187, First Quarter 2020

Page 47

Review by Mark Klobas

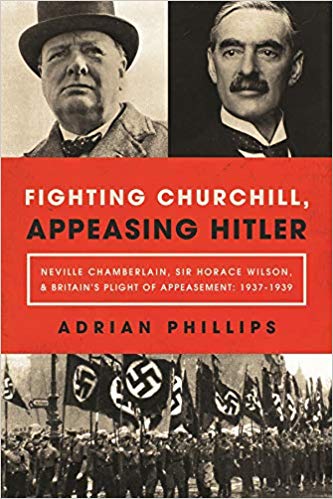

Adrian Phillips, Fighting Churchill, Appeasing Hitler: Neville Chamberlain, Sir Horace Wilson, and Britain’s Plight of Appeasement, 1937–1939, Pegasus Books, 2019, 368 pages, $29.95. ISBN 978–1643132211

Mark Klobas teaches history at Scottsdale College.

The eightieth anniversary of the start of the Second World War was accompanied by a predictable flurry of works about British efforts to appease Germany up to September 1939. Adrian Phillips’ book is the latest of this kind and follows close upon similar studies by Tim Bouverie (reviewed FH 187) and Robert Crowcroft (reviewed FH 184). Whereas Bouverie and Crowcroft summarized broadly the efforts to avert war by accommodating Adolf Hitler’s demands, Phillips focuses more specifically on the role of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s chief advisor Sir Horace Wilson in promoting appeasement.

Phillips’s focus is welcome, since Wilson remains one of the most understudied figures of the period. A child of lower-middle class parents, he rose rapidly from the Second Class of the British Civil Service to its heights by virtue of hard work and ability. Chosen as Permanent Secretary of the nascent Ministry of Labour, Wilson showed skill in resolving industrial disputes, making him an indispensable figure for the governments of the interwar period.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Wilson first crossed paths with Winston Churchill before the First World War when Wilson was a young civil servant and Churchill President of the Board of Trade, his first Cabinet-level position. At their meeting, Churchill was so caustic that Wilson would recount it decades later whenever explaining his views of the man. Churchill, though, seemed unaffected and even sought Wilson’s advice about an industrial matter twenty years later. Phillips suggests, however, that their disastrous first encounter permanently poisoned Wilson’s view of Churchill.

By contrast, Wilson got along famously with Chamberlain. Seconded to the Prime Minister’s office when Stanley Baldwin returned to Number 10 in 1935, Wilson reached the apogee of his power when Chamberlain became premier two years later. With the prime minister’s office a fraction of its current size, Wilson exerted enormous influence. He became a de facto chief of staff, with an office in Downing Street adjacent to the Cabinet Room. Wilson further strengthened his position by carefully nurturing Chamberlain’s vain ego, earning the Prime Minister’s trust but dangerously blurring the line between political master and civil servant. Together the two men became an effective team at directing government policy.

Their policy was to pursue appeasement. Though he had little experience in foreign affairs—he spoke no German, and his involvement in international relations prior to 1937 consisted of participating in the Imperial Economic Conference in Ottawa five years previously—Wilson shared Chamberlain’s priorities as well as a conviction in the correctness of their judgment. Phillips details the ways in which Chamberlain and Wilson sought to bring an enduring peace to Europe, often against a determined but scattered opposition. Churchill appears periodically in the text as a foil for the two men and is portrayed by Phillips as a true prophet, but one prone to errors that gave Chamberlain and Wilson openings to undercut his advocacy.

Phillips emphasizes throughout the book Chamberlain’s fervent belief that appeasement was the means to achieving a lasting peace in Europe while his opponents were risking war. Even after Germany’s occupation of the rump of Czechoslovakia in March 1939 proved that Churchill had been correct, Chamberlain discouraged a more robust rearmament effort and still sought ways of accommodating Hitler’s ambitions.

Wilson remained at the center of Chamberlain’s endeavors throughout. He worked to frustrate Churchill and his supporters and continued engaging in back-channel diplomacy well into the summer of 1939. Though Wilson remained a prominent figure in Chamberlain’s government even after the war began, one of Churchill’s first actions as prime minister in May 1940 was to banish Wilson from Downing Street, leaving him to carry on as a much-diminished head of the Civil Service until he qualified for his retirement pension in 1942. Wilson’s activities were long hidden behind the closed doors of the Cabinet Office. By sifting through the archival record, however, Phillips has successfully pieced together Wilson’s contributions to Chamberlain’s efforts and revealed the degree of Wilson’s subsequent disingenuousness when downplaying his involvement in events. While the title oversells the degree to which Phillips’s book is centered on the clash between Churchill and Chamberlain (the British edition has an even more melodramatic subtitle: “How a British Civil Servant Helped Cause the Second World War”), this is nonetheless a valuable study of Chamberlain’s pursuit of appeasement that provides the long-needed full details of Wilson’s involvement in the whole sorry business.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.