Finest Hour 186

“We Have Not Tried in Vain” Churchill Surveys the Post-war World

Churchill visiting Eisenhower in Washington, 1959, with his private secretary Sir Anthony Montague Browne

January 12, 2020

Finest Hour 186, Fourth Quarter 2019

Page 34

By Sir Winston S. Churchill

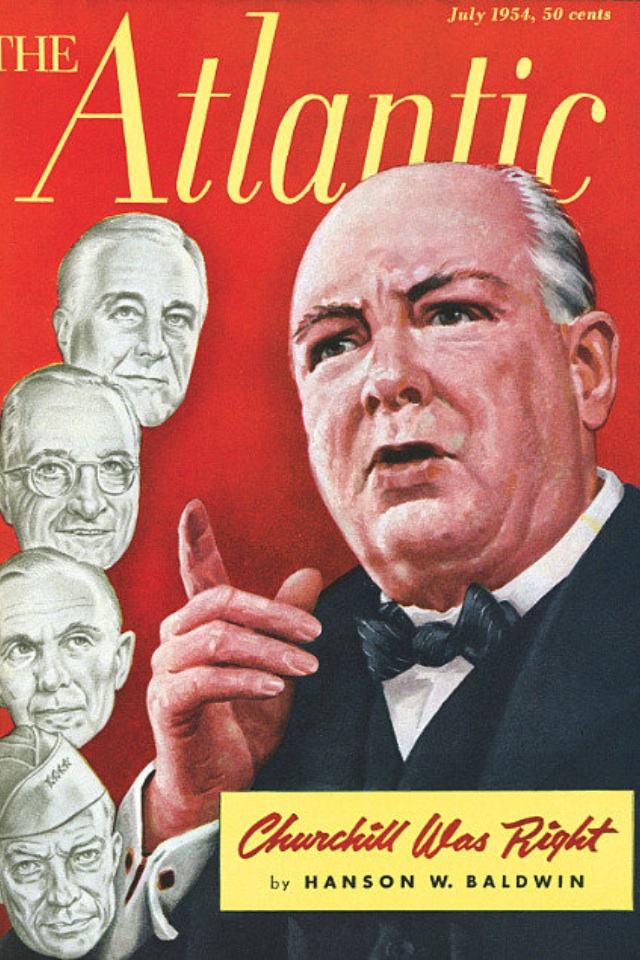

Winston Churchill’s views on the Cold War are fairly represented in two different sets of remarks that he composed at the time. The first came in a speech he made in Washington. The second came in what was his last work of original writing intended for publication.

IN CONGRESS, 17 JANUARY 1952

Shortly after he became Prime Minister for the second time in October 1951, Churchill travelled to Washington for high-level meetings with President Truman (see story on page 18). During this visit, Churchill was invited to speak before a meeting of both houses of Congress for the third time. Here follow excerpts from that speech:

The changes that happened since I last spoke to Congress [in 1943] are indeed astounding. It is hard to believe that we are living in the same world. Former allies have become foes. Former foes have become allies. Conquered countries have been liberated. Liberated nations have been enslaved by Communism.

Russia, eight years ago our brave ally, has cast away the admiration and good will her soldiers had gained for her by their valiant defence of their own country. It is not the fault of the Western Powers if an immense gulf has opened between us. It took a long succession of deliberate and unceasing works of acts and hostility to convince our peoples—as they are now convinced—that they have another tremendous danger to face and that they are now confronted with a new form of tyranny and aggression as dangerous and as hateful as that which we overthrew.

We Must Not Lose Hope

If I may say this, Members of Congress, be careful above all things, therefore, not to let go of the atomic weapons until you are sure, and more than sure, that other means of preserving peace are at your hands. It is my belief that by accumulating deterrents of all kinds against aggression we shall, in fact, ward off the fearful catastrophe, the facts of which darken the life and mar the progress of all the peoples of the globe. We must persevere steadfastly and faithfully in the task to which, under United States leadership, we have solemnly bound ourselves. Any weakening of our purpose, any disruption of our organization would bring about the very evils which we all dread, and from which we all suffer, and from which many of us would perish.

We must not lose patience, and we must not lose hope. It may be that presently a new mood will reign behind the Iron Curtain. If so it will be easy for them to show it, but the democracies must be on their guard against being deceived by a false dawn. We seek or covet no one’s territory; we plan no forestalling war; we trust and pray that all will come right. Even during these years of what is called the “Cold War,” material production in every land is constantly improving through the use of new machinery and better organization and the advance of peaceful science. But the great bound forward in progress and prosperity for which mankind is longing cannot come till the shadow of war has passed away.

There are, however, historic compensations for the stresses which we suffer in the “Cold War.” Under the pressure and menace of Communist aggression the fraternal association of the United States with Britain and the British Commonwealth, and the new unity growing up in Europe—nowhere more hopeful than between France and Germany—all these harmonies are being brought forward, perhaps by several generations in the destiny of the world. If this proves true—and it has certainly proved true up to date—the architects in the Kremlin may be found to have built a different and far better world structure than what they planned.

EPILOGUE TO THE SECOND WORLD WAR

After his retirement as Prime Minister in 1955, Churchill published a single-volume abridgement of his six-volume Memoirs of the Second World War prepared by his literary assistant Denis Kelly. To this Churchill added an Epilogue dated February 10, 1957. He was paid £20,000 for the additional 10,000 words. “I believe this is the highest amount ever paid for a manuscript, £2 per word,” Churchill’s agent Emery Reves observed. The text deserves close attention, for it contains not only Churchill’s observations on the Cold War up to that time but his optimistic beliefs about the future. Here follow extracts:

I have always held, and hold, the valiant Russian people in high regard. But their shadow loomed disastrously over the postwar scene. There was no visible limit to the harm they might do. Intent on victory over the Axis Powers, Britain and America had laid no sufficient plans for the fate and future of occupied Europe. We had gone to war in defence not only of the independence of smaller countries but to proclaim and endorse the individual rights and freedoms on which this greater morality is based. Soviet Russia had other and less disinterested aims. Her grip tightened on the territories her armies had overrun. In all the satellite states behind the Iron Curtain, coalition governments had been set up, including Communists.

It was hoped that democracy in some form would be preserved. But in one country after another the Communists seized the key posts, harried and suppressed the other political parties, and drove their leaders into exile. There were trials and purges. Rumania, Hungary, and Bulgaria were soon engulfed. At Yalta and Potsdam I had fought hard for Poland, but it was in vain. In Czechoslovakia a sudden coup was carried out by the Communist Ministers, which sharply alerted world opinion. Freedom was crushed within and free intercourse with the West was forbidden. Thanks largely to Britain, Greece remained precariously independent. With British and later American aid, she fought a long civil war against the insurgent Communists. When all had been said and done, and after the long agonies and efforts of the Second World War, it seemed that half Europe had merely exchanged one despot for another.

Today, these points seem commonplace. The prolonged and not altogether unsuccessful struggle to halt the destroying tide of Russian and Russian-inspired incursion has become part of our daily lives. Indeed, as always with a good cause, it has sometimes been necessary to temper enthusiasm and to disregard optimism. But it was not easy at the time to turn from the contemplation of a great and exhausting victory over one tyranny to the prospect of a tedious and expensive campaign against another.

NATO

The work that followed was complex. It resulted in the setting up of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, headed by a military planning staff under General Eisenhower at Versailles. From the efforts of the Supreme Headquarters Atlantic Powers Europe, of SHAPE as it was called, there gradually grew a sober confidence that invasion from the East could be met by an effective resistance. Certainly in its early stages the Atlantic Treaty achieved more by being than by doing. It gave renewed confidence to Europe, particularly to the territories near Soviet Russia and the satellites. This was marked by a recession in the Communist parties in the threatened countries, and by a resurgence of healthy national vigour in Western Germany.

The Bomb

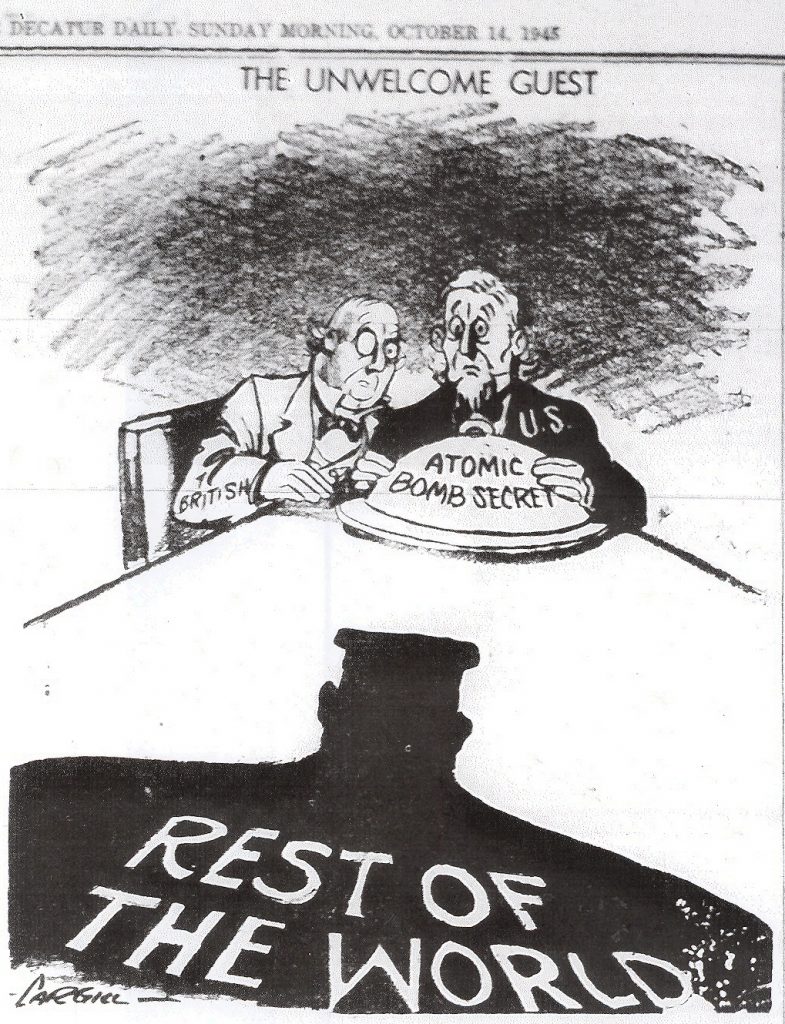

As the stark and glaring background to all our cogitations on defence lay man’s final possession of the perfected means of human destruction: the atomic weapon and its monstrous child, the hydrogen bomb. In the early days of the war Britain and the United States had agreed to pool their knowledge, and experiments in nuclear research, and the fruits of years of discovery by English pioneer physicists were offered as a priceless contribution to the vast and most secret joint enterprise set on foot in the United States and Canada. Those who created the weapons possessed for a few years the monopoly of a power which might in less scrupulous hands have been used to dominate and enslave the entire world. They proved themselves worthy of their responsibilities, but secrets were soon disclosed to the Soviet Union which greatly helped Russian scientists in their researches. Henceforward most of the accepted theories of strategy were seen to be out of date, and a new undreamed-of balance of power was created, a balance based on the ownership of the means of mutual extermination.

At the end of the war I felt reasonably content that the best possible arrangement had been made in the agreement which I concluded with President Roosevelt in Quebec in 1943. Therein Britain and America affirmed that they would never use the weapon against each other, they would not use it against third parties without each other’s approval, that they would not communicate information on the subject to third parties except by mutual consent, and that they would exchange information on technical developments. I do not think that one could have asked for more.

However, in 1946 a measure was passed by the American Congress which most severely curtailed any chance of the United States providing us with information. Senator [Brien] McMahon, who sponsored the bill, was at the time unaware of the Quebec Agreement, and he informed me in 1952 that if he had seen it there would have been no McMahon Act.

American Leadership

It was in this, then, the American possession or preponderance of nuclear weapons, that the surest foundation of our hopes for peace lay. The armies of the Western Powers were of a comparative insignificance when faced with the innumerable Russian divisions that could be deployed from the Baltic to the Yugoslav frontier. But the certain knowledge that an advance on land would unleash the devouring destruction of strategic air attack was and is the most certain of deterrents.

For a time, when the United States was the sole effective possessor of nuclear weapons, there had been a chance of a general and permanent settlement with the Soviet Union. But it is not the nature of democracies to use their advantages in threatening and dictatorial ways. Certainly the state of opinion that prevailed in those years would not have tolerated anything in the way of rough words to our late ally, though this might well have forestalled many unpleasant developments.

Instead the United States, with our support, chose a most reasonable and liberal attitude to the problems of controlling the use of nuclear weapons. Soviet opposition to efficient methods of supervision brought this to nothing. In former days no country could hope to build up in secret military forces vast enough to overwhelm a neighbor. Now the means of destruction of many millions can be concealed in the space of a few cubic yards.

New Strategies

Every aspect of military and political planning was altered by these developments. The vast bases needed to sustain the armies of the two world wars have become the most vulnerable of targets. All the workshops and stores on the Suez Canal, which had fed the Eighth Army in the desert, could vanish in a flash at the stroke of a single aircraft. Harbours, even when guarded by anti-aircraft guns and fighter planes, could become the graveyards of the fleets they had once protected. The evacuation of non-combatants from the cities was a practical proposition even in the days of highly developed bombing methods in the last war. Now, desirable though they may be, such measures are a mere palliative to the flaring ruin of nuclear attack. The whole structure of defence had to be altered to meet the new situation. Conventional forces were still needed to keep order in our possessions…but we could not afford enough of them because nuclear weapons and the means of delivering them were so expensive.

The nuclear age transformed relations between the Great Powers. For a time I doubted whether the Kremlin accurately realised what would happen to their country in the event of war. It seemed possible that they neither knew the full effect of the atomic missiles nor how efficient were the means of delivering them. It even occurred to me that an announced but peaceful aerial demonstration over the main Soviet cities, coupled with the outlining to the Soviet leaders of some of our newest inventions, would produce in them a more friendly and sober attitude. Of course such a gesture would not have been accompanied by any formal demands, or it would have taken on the appearance of a threat and ultimatum. But Russian production of these weapons and the remarkable strides of their air force have long since removed the point of this idea. Their military and political leaders must now be well aware of what each of us could do to the other.

A Gentler Breeze

Hopes of more friendly contacts with Russia remained much in my mind, and the death of Stalin in March 1953 seemed to bring a chance. I was again Prime Minister. I regarded Stalin’s death as a milestone in Russian history. His tyranny had brought fearful suffering to his own country and to much else of the world. In their fight against Hitler, the Russian people had built up an immense goodwill in the West, not least of all in the United States. All this had been impaired. In the dark politics of the Kremlin, none could tell who would take Stalin’s place. Fourteen men and one hundred eighty million people lost their master.

The Soviet leaders must not be judged too harshly. Three times in the space of just over a century Russia has been invaded by Europe. Borodino, Tannenberg, and Stalingrad are not to be forgotten easily. Napoleon’s onslaught is still remembered. Imperial and Nazi Germany were not forgiven. But security can never be achieved in isolation. Stalin tried not only to shield the Soviet Republics behind an iron curtain, military, political, and cultural. He also attempted to construct an outpost line of satellite states, deep in Central Europe, harshly controlled from Moscow, subservient to the economic needs of the Soviet Union and forbidden all contact or communion with the free world, or even with each other.

No one can believe that this will last forever. Hungary has paid a terrible forfeit. But to all thinking men, certain hopeful features of the present situation must surely be clear. The doctrine of Communism is slowly being separated from the Russian military machine. Nations will continue to rebel against the Soviet Colonial Empire, not because it is Communist, but because it is alien and oppressive. An arms race, even conducted with nuclear weapons and guided missiles, will bring no security or even peace of mind to the great powers which dominate the landmasses of Asia and North America, or to the countries which lie between them. I make no plea for disarmament. Disarmament is a consequence and manifestation of free intercourse between peoples. It is the mind which controls the weapon, and it is to the minds of the peoples of Russia and her associates that the fee nations should address themselves.

But after Stalin’s death it seemed that a milder climate might prevail. At all events it merited investigating, and I so expressed myself in the House of Commons on May 11, 1953. An entirely informal conference between the heads of the leading powers might succeed where repeated acrimonious exchanges at lower levels had failed. I made it plain that this could not be accompanied by any relaxation of the comradeship and preparations of the free nations, for any slackening of our defence efforts would paralyze every beneficial tendency towards peace. This is true today. What I sought was never fully accomplished. Nevertheless for a time a gentler breeze seemed to blow upon our affairs. Further opportunities will doubtless present themselves, and they must not be neglected.

Opportunity-for-All

I do not intend to suggest that all the efforts and sacrifices of Britain and her allies recorded in the six volumes of my War Memoirs have come to nothing and led only to a state of affairs more dangerous and gloomy than at the beginning. On the contrary, I hold strongly to the belief that we have not tried in vain. Russia is becoming a great commercial country. Her people experience every day in growing vigour those complications and palliatives of human life that will render the schemes of Karl Marx more out of date and smaller in relation to world problems than they have ever been before. The natural forces are working with greater freedom and greater opportunity to fertilise and vary the thoughts and the power of individual men and women. They are far bigger and more pliant in the vast structure of a mighty empire than could ever have been conceived by Marx in his hovel.

And when war is itself fenced about with mutual extermination it seems likely that it will be increasingly postponed. Quarrels between nations, or continents, or combinations of nations there will no doubt continually be. But in the main human society will grow in many forms not comprehended by a party machine. As long therefore as the free world holds together, and especially Britain and the United States, and maintains its strength, Russia will find that Peace and Plenty have more to offer than exterminatory war. The broadening of thought is a process which acquires momentum by seeking opportunity for all who claim it. And it may well be if wisdom and patience are practiced that Opportunity-for-All will conquer the minds and restrain the passions of mankind.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.