Finest Hour 183

Georgina Landemare: The Churchills’ Longest-serving Cook

Mrs. Landemare with her granddaughter

April 17, 2019

Finest Hour 183, First Quarter 2019

Page 30

By Annie Gray

Annie Gray is a historian specialising in British food and dining c.1650–1950. Her biography of Georgina Landemare, Victory in the Kitchen: The Story of Churchill’s Cook, is due out in spring 2020.

Long-time Finest Hour readers will be familiar with the name Georgina Landemare. She was, along with Grace Hamblin and Victor Vincent (the Chartwell gardener), one of the longest-serving of the Churchills’ paid retinue, with them on and off (mainly on) for twenty-two years. She catered networking parties during Churchill’s Wilderness Years, policy-making gatherings when he was Prime Minister during the War, and family get-togethers during his bitter postwar years in opposition. Mrs. Landemare tends to have only a walk-on role in the many books about the Churchills, however—a surprising omission, given the important role she played in the smooth running of the family home.

Georgina’s early life was entirely average. She was born into what was categorised at the time as the “affluent working class,” meaning working class people with jobs and steady wages. Her father was a coachman, her mother a maid. They were from Hertfordshire, and Georgina was born at her maternal grandmother’s house in Aldbury, near Tring. Today it is a commuter village for London, but it remains a chocolate-box style picture of English countryside sweetness. When I visited there last winter, it was snowing, and I hid in the firelit warmth of the local pub—at one time run by relatives of Georgina’s mother—trying to visualise it as it was in 1882 when Georgina was born: a struggling rural outpost ruled by a handful of local gentry families. She never lived there, however, moving at a young age with her family to London. She started work at thirteen, and then, aged fifteen, became a scullery maid in a house in Kensington Palace Gardens. Looking back, she described it as “starting her track of life,” even then determined that service would be a career and not merely a job.

Georgina spent the next ten years working her way up the kitchen hierarchy, making cook by the time she was twenty-five. All of her employers were rich and well connected. They all had large establishments too, but most were not quite at the level where they could afford permanent male chefs. Men cost approximately double the wage of a woman and were seen as more prestigious and more able to produce high end cookery than their female equivalents. One of the more significant households Georgina worked for was that of Ian and Jean Hamilton. They were part of the Churchill set, and it was while working as a kitchen maid for them around 1905 that she probably first cooked for Winston Churchill. In 1909 she left live-in service when she married Paul Landemare, a French chef who had worked in both hotels and private service for the aristocracy.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Both Clementine Churchill and Mary Soames credited Paul for training Georgina in the ways of French cookery, although she was clearly a skilled and hard-working professional before her marriage. In the twenty-three years of her married life, she built upon her foundation learning on the job in English kitchens and added to her existing repertoire the more formal training Paul had had in the classical French tradition. The Churchills’ youngest daughter Mary later described Mrs. Landemare as “a superb cook, combining the best of French and English skills.” When Paul died in 1932, Georgina went solo. Already established as a presence on the culinary scene, she found no difficulty in building up an impressive client list. From 1933 that list included Winston and Clementine Churchill, who used her to cater both occasional events and also to cover for their more permanent cooks when they were away or had unexpectedly left without a replacement being organised.

Mrs. Landemare Goes to War

The Churchills’ servants are a difficult group to trace. Financial precariousness, combined with being demanding employers for the salaries they could afford, meant that they struggled to recruit and retain staff. Clementine, who knew her way around a kitchen after a childhood spent in genteel semi-poverty, habitually took on untrained girls and taught them how to cook. She sought out recipes for the staff to try, annotated the daily menu books very closely, and relied on Maryott Whyte (her cousin and Mary’s nurse and lifelong friend) to fish them out of trouble when necessary. When the Churchills could afford to employ Mrs. Landemare for a weekend, it was a glorious relief.

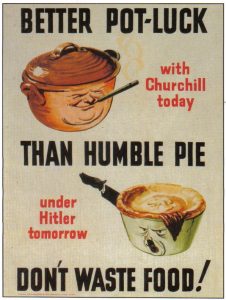

At the outbreak of the Second World War, the Churchills were in particularly straightened times, having seriously considered selling Chartwell the previous year. It is therefore unsurprising that when, in early 1940, Mrs. Landemare offered her services as a permanent cook, the Churchills—or rather Clementine, since she masterminded domestic matters—leapt at the opportunity. For Mrs. Landemare it meant steady work instead of the freelance jobs she had been relying upon and which would certainly dry up during the war. For the Churchills it meant having a fantastic cook, one whom they could certainly not afford and whose skills would enable them not simply to “make the most of the ration,” as Clementine later put it (Winston barely knew what the ration was) but also to entertain important visitors in a way which would impress and delight them. Diplomacy over a dinner table had long been part of the Churchill modus operandus, and, while he was fond of his food and never shirked on fine (generally expensive) ingredients and alcohol, his overwhelming interest in meals came from the possibilities they held for informal networking and politicking ,away from the normal machinery of state.

Throughout the war years, Mrs. Landemare cooked meals that consistently met with praise. She dealt deftly and calmly with people and circumstance alike. Churchill was notoriously fussy as an eater and wedded to particular dishes, such as the jellied consommé he had before bed (it went with him on trips abroad where practical) and roast beef. Recognising the power of food for promoting his image, Churchill assiduously cultivated a reputation as a man who liked plain food and British dishes. No hints of the true, rather more complex menus served at Downing Street and Chequers during the war escaped to sully this image.

Mrs. Landemare’s meals made careful use of vegetables from Chartwell and Chequers, additional eggs and meat from the diplomatic allowances, and gifts of more esoteric items such as maple syrup from connections abroad. She kept a handwritten recipe book, which attests to the many influences on her cookery, including Churchill’s trips to North America. She also had to deal with the physical circumstances of the war, which included a bomb exploding metres away from the Downing Street kitchen that she had vacated for the shelter mere minutes before at the prescient urging of the Prime Minister himself. She later said he had certainly saved her life that night.

Faithful Servant

By the time the war finally ended with the defeat of Japan in August 1945, Churchill was already out of office. Mrs. Landemare remained his London cook for another nine years, first at Hyde Park Gate and then again at Downing Street from 1951. She kept returning as a temp even after her official retirement in 1954. During those years, she and Clementine in particular formed a close bond, and they remained in contact until the latter’s death in 1977.

Menu books from the late 1940s, when food rationing continued, show how the shrewd cook kept the reality of such things as dried eggs away from Churchill and reserved any necessary scrimping for the servants. Mrs. Landemare was, however, responsible for showing Churchill what the ration looked like. One day she laid out the full food allowance for one person on a tray for Churchill to examine. “Not bad” came his response, which turned to mild shock when she explained that it was for an entire week—not one day as her employer first assumed.

In retirement, Mrs. Landemare struggled to cope after a life dedicated to serving others. She felt lost. It was Clementine’s idea that her former cook should write up some of her recipes for publication. Clementine even provided a foreword to the eventual book, which added to its cachet. Recipes from No 10 sold very well at first, but by 1960 it was old news and went out of print. Mrs. Landemare lived for another eighteen years, outliving first Winston and then Clementine before her own peaceful death, aged ninety-six, in 1978.

Like so many of the Churchills’ staff, Mrs. Landemare remained loyal until the end, telling only a few tried and tested stories about her time with them. She quite literally tore up her own life story, having written and then destroyed a memoir in the mid-1970s. I have spent the last year or so reconstructing it, exploring through her not just a twentieth-century servant’s life and the history of upper class food, but also shedding light on one of the few aspects of Churchill not really considered so far. He was a man used to being surrounded by servants, but they remain frustratingly invisible, not only in his biographies but also—to be fair to his biographers—in the wealth of archival material concerning him. Many were but a fleeting presence, others were short-term but important (Frank Sawyers, his valet during the war, comes to mind.) None was so long-lasting and so integral to Churchill’s everyday life as Georgina Landemare. As Churchill himself said, “it is well to remember that the stomach governs the world.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.