Finest Hour 182

The World Crisis Breeds New Publishing Relationships for Churchill

February 20, 2019

Finest Hour 182, Fall 2018

Page 36

By Ronald I. Cohen

Ronald I. Cohen MBE is author of A Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill, 3 vols. (2006).

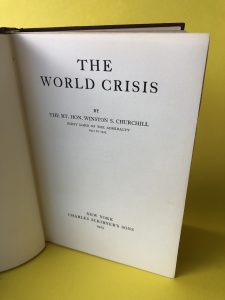

This is a behind-the-scenes article. It focuses not on the content of The World Crisis (which former Prime Minister A. J. Balfour described as “Winston’s brilliant Autobiography, disguised as a history of the universe”) but rather on how that multi-volume history of the Great War—Churchill’s twelfth work—came to be published in both the UK and the USA.

As an established author, Winston Churchill had had a number of publishing relationships on both sides of the Atlantic, some of which were more enduring than others. His first was with Longmans Green, which had published his first five books (from the The Story of the Malakand Field Force to Ian Hamilton’s March) in both London and New York between 1898 and 1900. Then, after a brief fling with Macmillan (which had overpaid for the rights to Lord Randolph Churchill), Churchill moved to Hodder & Stoughton in London between 1908 and 1910 for the publication of My African Journey and the speech volumes Liberalism and the Social Problem and the now exceedingly rare The People’s Rights.

2025 International Churchill Conference

There followed a publication famine from Churchill’s appointment as First Lord of the Admiralty in 1911 through the end of the decade. Consequently, when Churchill determined to write a history of the First World War, he had no obvious publishing firm to approach. He was very much a free agent.

Mr. Thornton Butterworth

By chance, on 22 October 1920, the Associated Newspapers asked Churchill to review the new Autobiography of Margot Asquith for the munificent sum of £250 (the rough equivalent of which today would be $12,200). The article appeared on 4 November, and Asquith’s grateful publisher Thornton Butterworth wrote Churchill five days later, saying:

I have been deeply gratified by your most recent admirable review in “The Daily Mail.” I was greatly impressed by the tactful kindness of such criticism as had to be adverse and entire fairmindedness shown to the book throughout….May I add that if at any time you decide to write a new book, I should esteem it a very great favour if you would allow me the privilege of publishing it.

Timing is everything. Churchill had just entered into a literary agency agreement with Curtis Brown (thereafter, and even today, his literary agents) regarding his First World War history. The deal with Butterworth was quickly made, Churchill securing an advance against royalties of £5,000 against the first volume (the initial deposit was a rich £2,000 or roughly $97,500 today) and, with the assistance of Butterworth, an agreement with The Times for a similar sum for the British serialisation of the first volume. The book contract was signed on 29 November 1920.

Connecting with Scribner’s

Since Butterworth had no publishing arm in the US, that market was open for Churchill’s new and still untitled book. It was Butterworth himself who proposed the project to Charles Kingsley, the London representative of US publisher Charles Scribner, who relayed to his boss the details provided to him by Butterworth:

As originally offered the book was to be in two volumes for publication in 1921 or 1922—probably the latter date….It will not be a very lengthy work, each volume probably containing not much over 100,000 words…. Butterworth was extremely anxious that I emphasise the fact that Churchill proposes to make all sorts of revelations; that large numbers of unpublished naval, diplomatic, and military papers will be brought to light, and that, in short, it will be a work of sensational character in which Churchill will fully live up to his reputation of being an “enfant terrible”.

Butterworth, Kingsley explained, “is anxious to throw the book our way if we care for it and frankly confesses that he does so in the hope of reciprocity on our part, but he is hesitant about doing so in the fear that we should have some feeling about doing business along these lines.” The British publisher was unequivocal regarding Churchill’s intentions; he “is frankly out for all the traffic will bear.”

Despite his view of Churchill’s financial ambitions for the work, Butterworth was so enthusiastic about the author’s writing skills that he almost seemed to be acting as Churchill’s agent when he advised Scribner of these talents in a letter several weeks later:

Under separate cover, I have sent your firm particulars concerning the Churchill book. Full as I have tried to make them, I cannot help feeling they fall very far short of what they should be to enable your firm to visualise its potentialities. But you will realise that Churchill is a statesman—a statesman of the first rank next to Lloyd George, but, unlike Lloyd George, he has the power—and the very great power of writing.

To encourage Scribner, Butterworth divulged that The Times had paid a considerable amount for the serial rights, and he disclosed the figure that he had contracted to pay Churchill. As Butterworth put it: “You may consider them [the terms that I am paying] somewhat high, doubtless they are, at the same time I anticipate on a very conservative estimate to make a very considerable profit.” He also explained that Curtis Brown was seeking other offers in the United States but that Scribner’s had been left to him. No financial benefit was to accrue to Butterworth; the commission on the American sale would benefit Churchill’s literary agent, Curtis Brown.

On 25 January, Charles Scribner cabled Butterworth: “Offer for Churchill twenty per cent royalty, tax free, with sixteen thousand dollars advance. Division of payments like your own.” Three days later, Butterworth cabled Scribner back, “CHURCHILL OFFER ACCEPTED.” Scribner was very pleased by the result and wrote Butterworth on 2 February:

We were delighted to hear that you had been able to secure for us the Churchill books and we owe you thanks on the double score of having given us your good offices, as well as having bagged the game….We should like to have a clause to the effect that the book publication should be simultaneous in Great Britain and the United States; and of course this is important to avoid copyright complications.

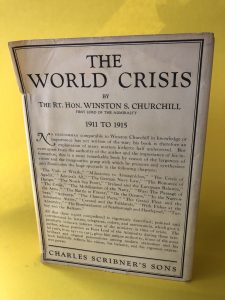

The contract (dated 8 February) anticipated delivery of 150,000–200,000 words in two volumes, the first to be delivered “not later than 31 December 1922” and the second within one year thereafter. Publication was to occur within one year of delivery of manuscript and the selling price was to be “not less than Five Dollars.” Scribner’s acquired the rights for the United States and Canada for an advance of $16,000 against royalties.

Charles Scribner had concerns about how well the book would fare. He was anxious about serialisation in the United States and expressed consternation that “publication by representative papers in different sections of the country would greatly lessen the sale of the book.” On the other side of the Atlantic, Thornton Butterworth was worried about the anticipated publication date of Lloyd George’s Memoirs, which, in the end, did not appear until a decade later. Scribner added that “the publication date should be earlier than April 1st [1923], as our Spring season is not as long as yours and a book published after that date has little chance.”

There was in any case no ill feeling between Churchill and Lloyd George regarding their potentially competing books. Churchill wrote Clementine that Lloyd George had “read two of my chapters in the train & was well content with the references to himself. He praised the style and made several pregnant suggestions wh[ich] I am embodying.” Churchill also observed more personally that “It is a g[rea]t chance to put my whole case in an agreeable form to an attentive audience. And the pelf will make us feel v[er]y comfortable.”

Defeat Helps

Ironically, Churchill’s subsequent political misfortune worked to his benefit as a writer. When he was defeated for re-election in 1922, Churchill spent the next two years outside Parliament. This gave him time “to go ahead polishing and revising.” He also had discussions with his publisher about length. Churchill recorded that Butterworth was insisting, “that the first volume must be one volume only and not two, but his reader thinks all the stuff so good that it is a pity to cut any of it out. I am not at all sure.”

Length was a serious issue. Contracted at 100,000 words, the manuscript ran to 165,000. This had the effect of increasing Butterworth’s production costs by approximately 70%, and he expressed an interest in reducing both the amount of the advance and the level of royalties in consequence. Needless to say, Churchill did not accede to his requests.

The Title

One of the matters that remained unresolved was the title. Among the ideas bandied about by Churchill in January and February 1923—only sixty days before publication—were: “The Administration of the Admiralty 1911 to 1916,” “The Great Amphibian,” “The World Convulsion,” “The Meteor Flag,” and “Within the Storm.” Butterworth offered: “The World Crisis 1911–1916,” “The Decisive Years 1911–1916,” and “My Admiralty Tenure.” Scribner and Butterworth together came up with: “The World Crisis,” “Sea Power and the World Crisis,” or “Sea Power in the World Crisis.” It is perhaps for this reason that when The Times began serialisation of the first volume on 8 February 1923, the paper simply titled it “Mr. Churchill’s Book,” which title they retained for further serialised volumes.

Finally, on 2 February, Churchill returned with “Fateful Days.” In Britain, Butterworth and Kingsley were at their wits’ end. Kingsley desperately cabled his boss in New York: “CHURCHILL WANTS TITLE FATEFUL DAYS PLEASE CABLE RETURN UNSATISFACTORY USING WORLD CRISIS.” And that was that.

The Publication Date

For many years it was thought, not unreasonably, that the British edition was the first edition of The World Crisis. While that may appear to be a nitpicking issue to readers of this article, it is an important one to booksellers and collectors and can be crucial to the legal question of copyright. In any case, it is clear that Frederick Woods, the earliest Churchill bibliographer, did not consider the Scribner correspondence with Churchill and Butterworth.

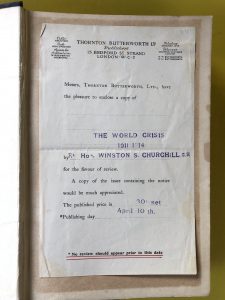

What did in fact happen was this: the British were indeed ready before the Americans, but ultimately they did not publish first. As soon as the dates for The Times serialisation were firmly established, Churchill announced that “Mr. Butterworth may therefore publish on March first.” Kingsley, though, was successful in holding back this date and informed Scribner on 23 February of his success:

Butterworth is I believe proving more reasonable than I expected in regard to publication date. He has given up all idea of publishing before Easter and asked me to-day when I thought we would be able to cable a date.

Churchill himself was pushing for an earlier date than Easter (1 April in 1923), either 14 or 21 March, but Kingsley responded by stating that the delay in the arrival of Churchill’s corrected proofs had made March publication an impossibility. He reminded Churchill and his literary representatives of the tacit understanding that simultaneous British and American publication had been agreed.

In a letter to Churchill on 4 April 1923, Scribner definitively established the date of Friday, 6 April. With that letter, Scribner included “two advance copies of the first volume of ‘The World Crisis’ which is to be published here on April 6th.” This date was confirmed in a letter of 9 April 1923 from the American publisher to A. W. Barmby (General Manager of the New York office of Churchill’s literary agent) in which Scribner’s sent the final payment due to author upon publication and stated:

Enclosed I am sending a cheque for $5,000 in payment of the advance royalty due on Winston Churchill’s “The World Crisis”, half of this sum being due on the delivery of the MS. and half on the day of publication, now settled as April 6th.

Given that Thornton Butterworth had been ready to proceed well before that date, it was ironic that first publication occurred on Friday, 6 April in the United States and only on Tuesday, 10 April in Great Britain. The fact that the American edition of The World Crisis is the first edition of the work is something I disclosed in my 2006 Bibliography.

As it happened, Churchill was very pleased by the American publication and wrote Scribner to this effect on 21 April:

I think they [referring to the two copies sent him] are admirably produced, and I am particularly struck by the fact that some serious mistakes which have been allowed to remain in the English Editions, have been pruned out by the vigilance of those charged with the make-up in America.

From this episode arose Churchill’s long publishing relationships with Thornton Butterworth and Charles Scribner during the inter-war years.

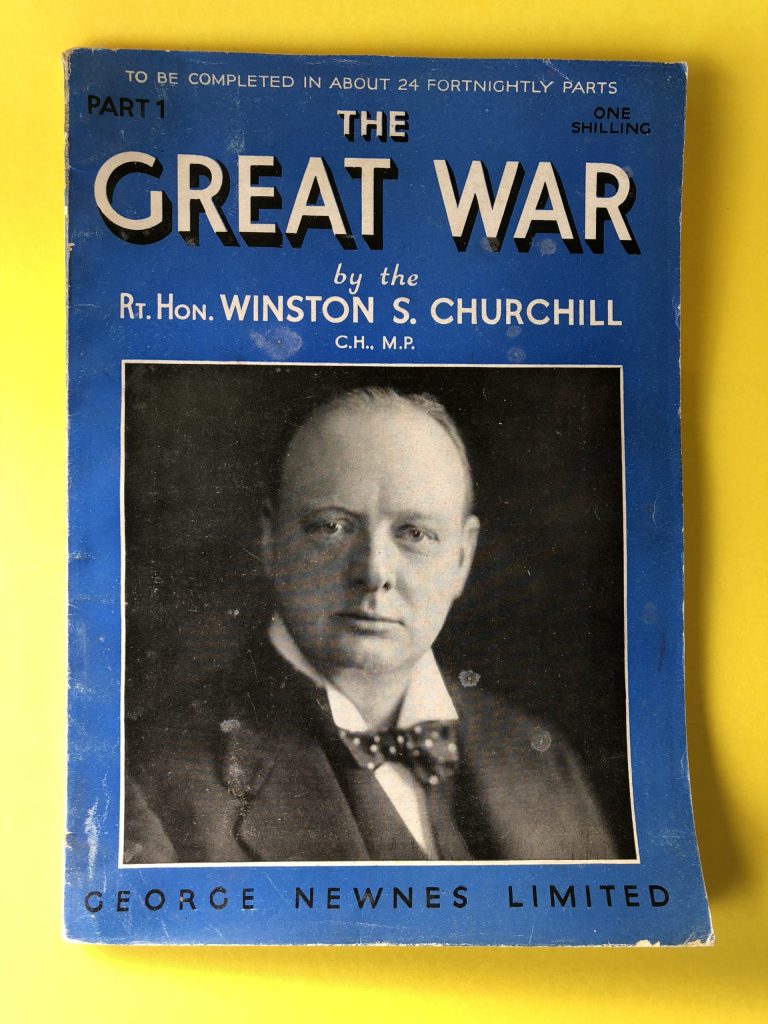

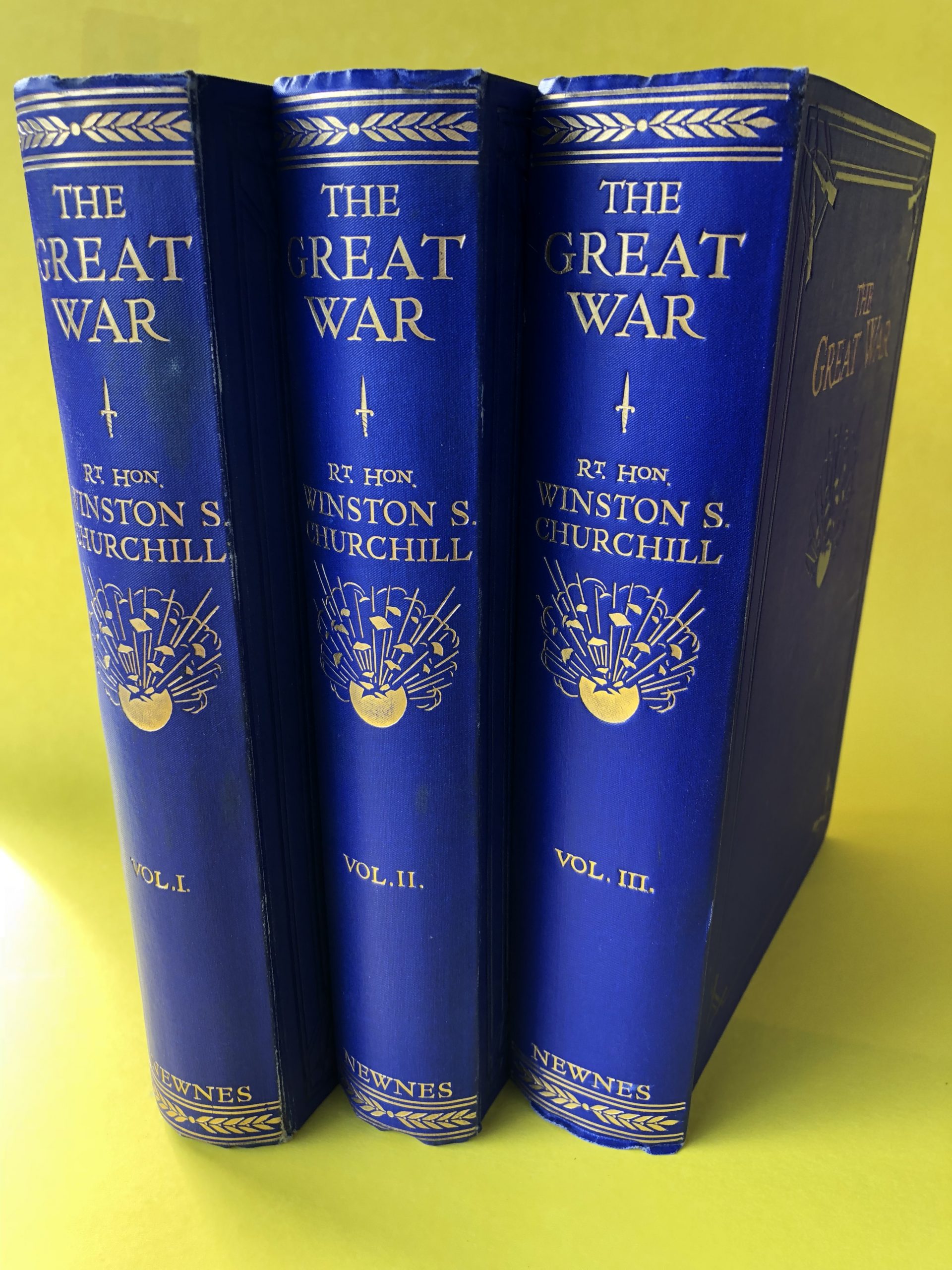

The End of the Affair

The World Crisis was first published in a format that we book aficionados describe as “five volumes in six.” The first three volumes are 1911–1914, 1915, and 1916–1918, with this last forever confusing the world by being published in two parts. Two more volumes came later: The Aftermath and The Eastern Front. In 1933–34, George Newnes issued an illustrated edition in twenty-six weekly parts as The Great War. Collectively these added up to a staggering 1,127,358 copies in print—an average of 43,360 per issue. Of these, 928,401 copies were sold at one shilling apiece, and 78,000 were bound in 3,000 sets of either three or four volumes each. One or another of the foregoing editions were translated into twelve languages: Czech, Danish, Finnish, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Norwegian, Russian, Serbian, Spanish, and Swedish, putting The World Crisis into third position as the most translated of Churchill’s works.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.