Finest Hour 181

Preparing for an Invasion of Britain… In Writing

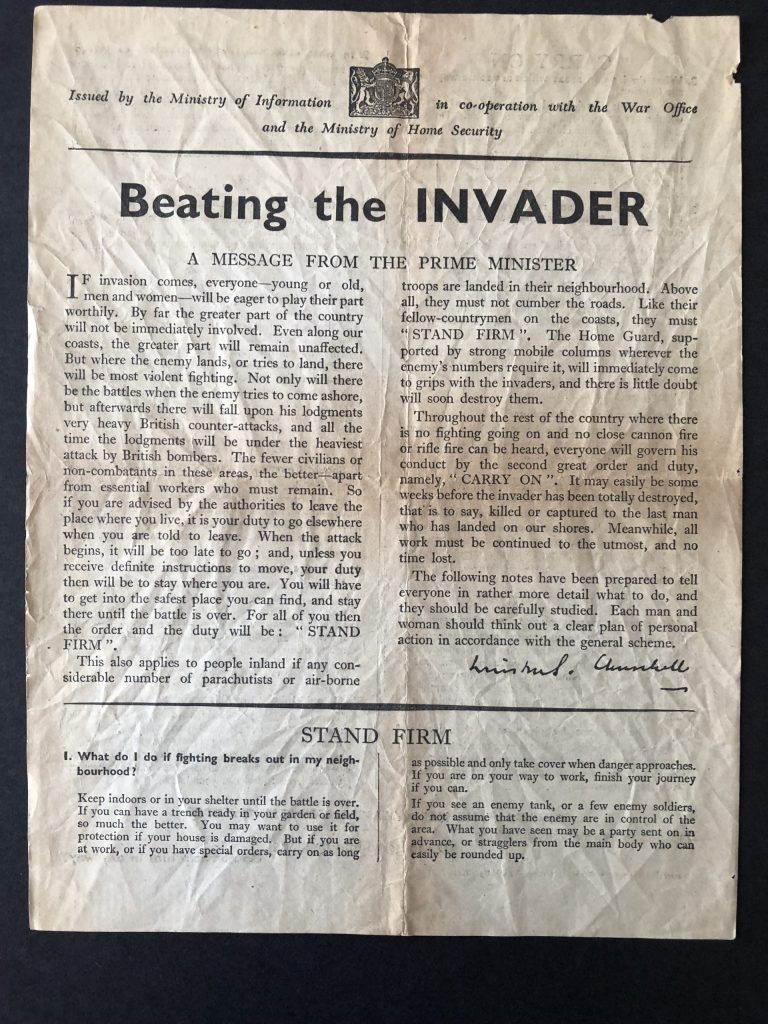

British Government leaflets advising citizens on how to respond to a German invasion.

October 24, 2018

Finest Hour 181, Summer 2018

Page 38

By Ronald I. Cohen

Ronald I. Cohen MBE is author of A Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill, 3 vols.(2006).

An Ottawa Churchill Society member and good friend referred me to an online article he had spotted by Colin Marshall entitled “Winston Churchill’s List of Tips for Surviving a German Invasion: See the Never-Distributed Document (1940).” Given the apparent obscurity of the leaflet to which it refers (to judge by the title of Marshall’s article), my Churchillian friend wondered if I was aware of the document. I was indeed.

I should note straightaway that, while it is designated by Marshall as “Churchill’s” list of tips, they were not initially drafted by him, although he certainly did comment on them and ultimately approved their substance—more on that following the issue of distribution.

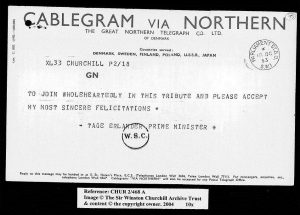

2025 International Churchill Conference

Far from “never-distributed,” the leaflet, boldly entitled Beating the Invader, was printed in huge numbers: 14,050,800 copies in English and 160,400 copies in Welsh, the latter under the title Trechu’r GORESGYNNYDD. Duff Cooper, then Minister of Information, sent a draft of the document to Churchill on 7 March 1941, asking the Prime Minister, “Would you consider writing…an introduction yourself? It would of course give the leaflet far greater authority and would induce many people to read and to keep it who might otherwise neglect to do so.”

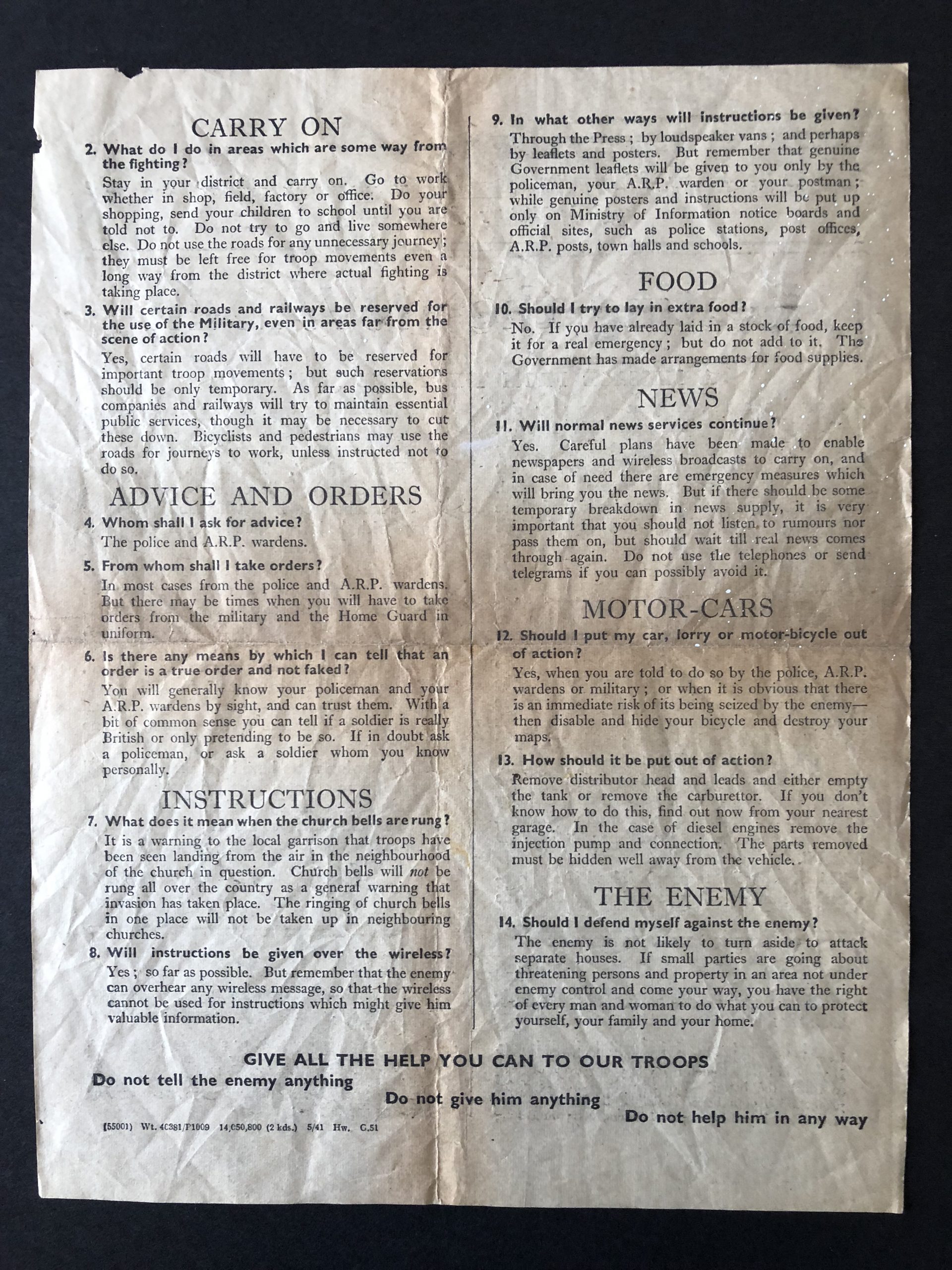

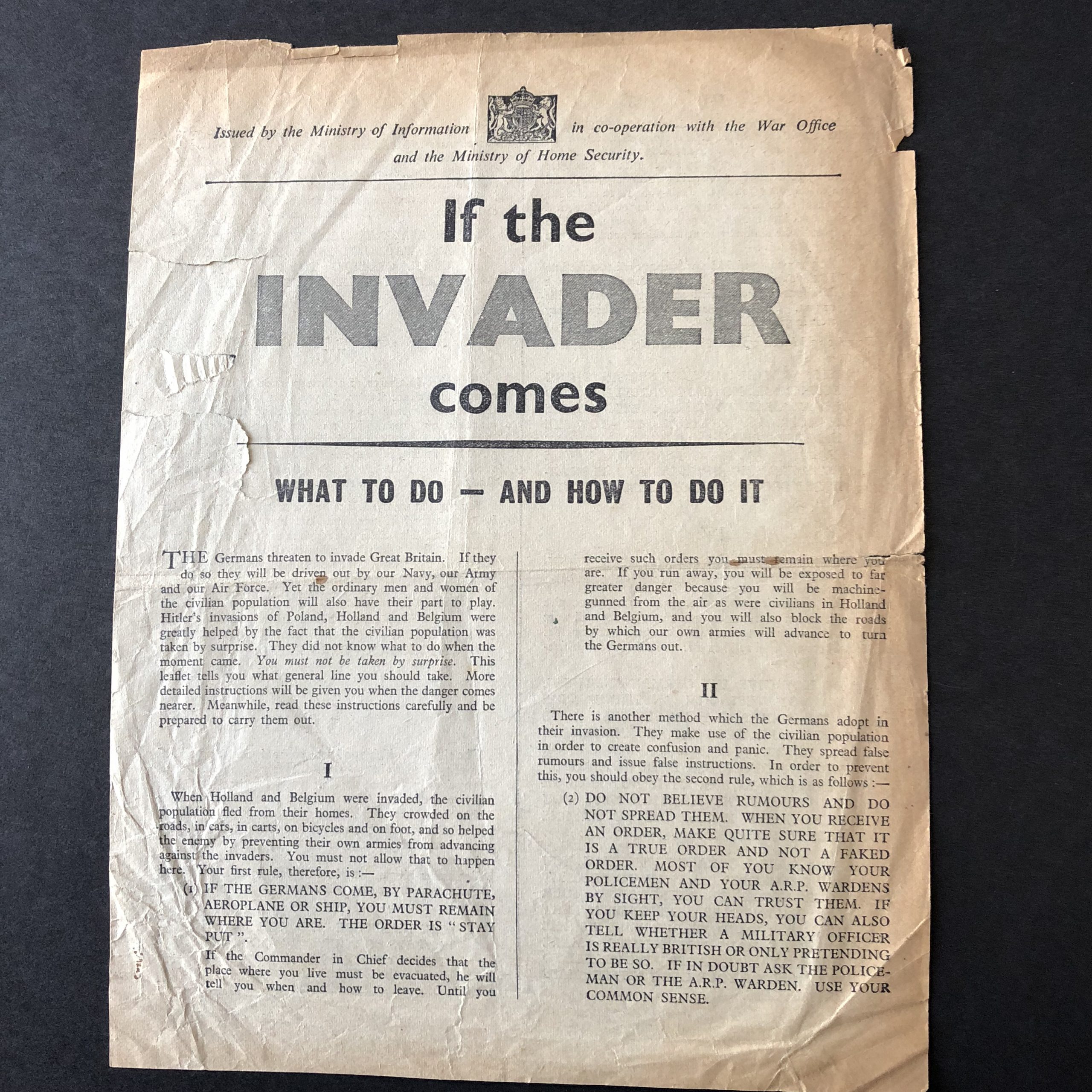

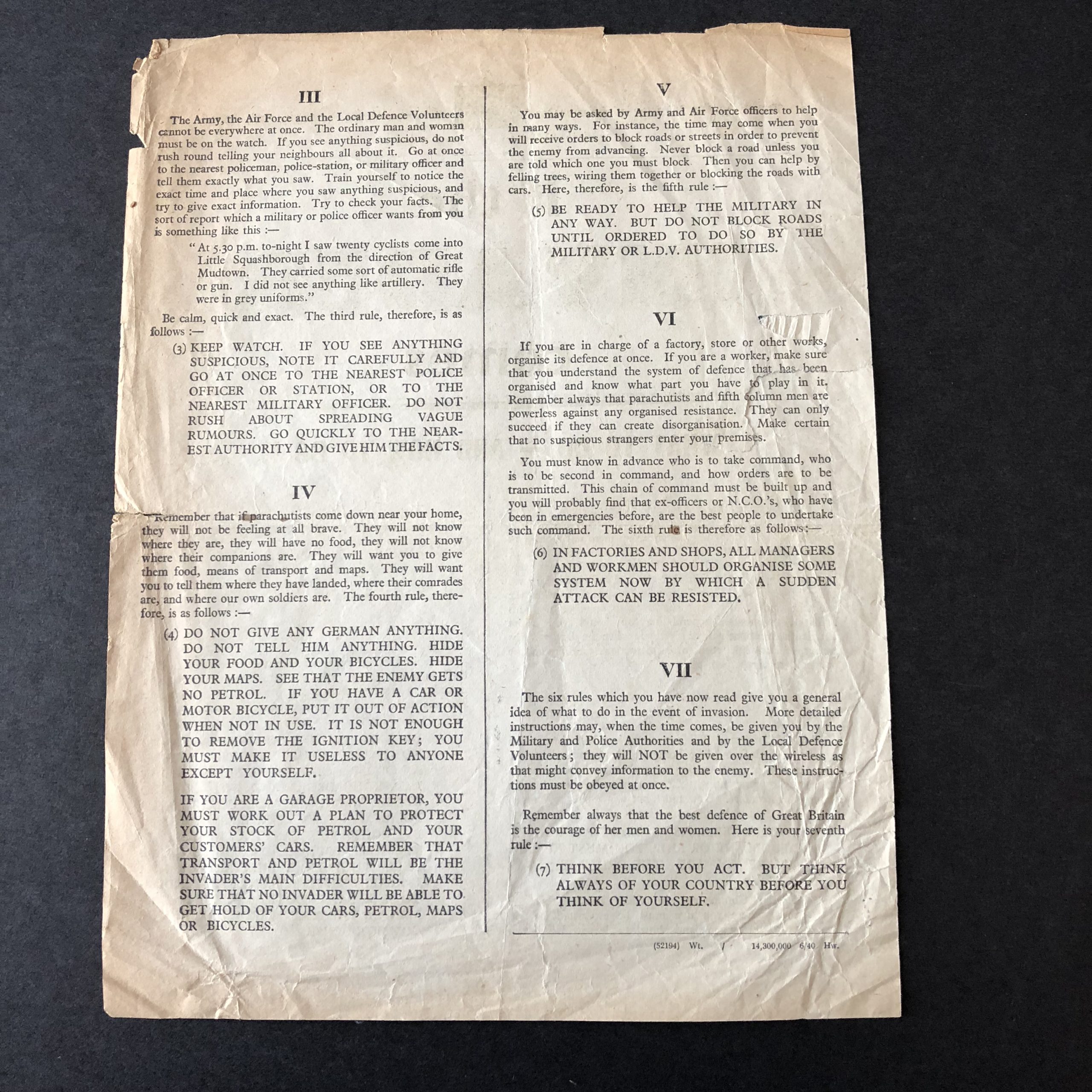

I should note here that about nine months before (in June 1940), the Ministry of Information had published a leaflet with, I expect, the same intended purpose and audience. Entitled If the Invader Comes, it listed seven rules, each lengthier in exposition than the fourteen in Beating the Invader, and without headings any more appealing than the Roman numerals I–VII. More important, there were no accompanying words from Churchill. Still the Ministry published 14,300,000 copies. One can readily appreciate that the astute Minister of Information foresaw a more effective way of communicating the defensive advice to the British people by making the text more appealing and getting their inspiring Prime Minister to introduce it.

I should note here that about nine months before (in June 1940), the Ministry of Information had published a leaflet with, I expect, the same intended purpose and audience. Entitled If the Invader Comes, it listed seven rules, each lengthier in exposition than the fourteen in Beating the Invader, and without headings any more appealing than the Roman numerals I–VII. More important, there were no accompanying words from Churchill. Still the Ministry published 14,300,000 copies. One can readily appreciate that the astute Minister of Information foresaw a more effective way of communicating the defensive advice to the British people by making the text more appealing and getting their inspiring Prime Minister to introduce it.

It had been initially contemplated by the War Cabinet that the new Beating the Invader text would be released in the Sunday newspapers on 16 March, but that never occurred. Churchill dictated his introduction on 25 March, and the proofs of the document went back and forth while everyone contemplated how it should be issued.

The final recommendation to distribute the leaflet to all British householders did not occur until the War Cabinet meeting of 24 April, which resulted in the printing of the millions of copies noted above. The huge print run might leave one with the impression that the leaflet would be commonly found today. It is not. Its relative scarcity is understandable; it was, after all, only a leaflet anticipating an event, which never came to pass. In the result, although it was very widely distributed, relatively few copies have survived.

The final recommendation to distribute the leaflet to all British householders did not occur until the War Cabinet meeting of 24 April, which resulted in the printing of the millions of copies noted above. The huge print run might leave one with the impression that the leaflet would be commonly found today. It is not. Its relative scarcity is understandable; it was, after all, only a leaflet anticipating an event, which never came to pass. In the result, although it was very widely distributed, relatively few copies have survived.

The list of “tips” covers a range of potential actions and reactions of the brave Britons, then essentially alone in their resistance to the Axis (with the obvious exception of Britain’s Commonwealth partners). The two-sided leaflet is characterized by all-caps subject headings such as “STAND FIRM” and “CARRY ON” and a series of fourteen questions and answers drafted by the Ministry of Information and issued under the combined authority of the War Office and the Ministry of Home Security.

While the document was prepared as a how-to or what-to-do document by Duff Cooper’s Ministry of Information, it opens with Churchill’s powerful and inspirational introduction, in which he begins with the bravery-invoking assumption, “If invasion comes, everyone—young or old, men and women—will be eager to play their part worthily.” Noting that the greater part of the country will be unaffected by any invading force, he assures his readers that the British forces will do their part, inflicting “very heavy British counter-attacks” on the enemy as they land by means of bomber attacks on their lodgments.

While the document was prepared as a how-to or what-to-do document by Duff Cooper’s Ministry of Information, it opens with Churchill’s powerful and inspirational introduction, in which he begins with the bravery-invoking assumption, “If invasion comes, everyone—young or old, men and women—will be eager to play their part worthily.” Noting that the greater part of the country will be unaffected by any invading force, he assures his readers that the British forces will do their part, inflicting “very heavy British counter-attacks” on the enemy as they land by means of bomber attacks on their lodgments.

He goes on: “The fewer civilians or non-combatants in these areas, the better—apart from essential workers who must remain. So if you are advised by the authorities to leave the place where you live, it is your duty to go elsewhere when you are told to leave. When the attack begins, it will be too late to go; and unless you receive definite instructions to move, your duty then will be to stay where you are. You will then have to get into the safest place you can find, and stay there until the battle is over. For all of you then the order and the duty will be: ‘STAND FIRM.’”

Even where there is not substantial fighting, presumably away from the coasts, Churchill advises that everyone must be bound by the second great order and duty, namely, “CARRY ON….It may easily be some weeks before the invader has been totally destroyed, that is to say, killed or captured to the last man who has landed on our shores. Meanwhile, all work must be continued to the utmost, and no time lost.”

Encouraging all to assume their part in the defence of their island home, he concludes his introduction by writing: “The following notes have been prepared to tell everyone in rather more detail what to do, and they should be carefully studied. Each man and woman should think out a clear plan of personal action in accordance with the general scheme.” And the document is influentially signed in facsimile: “Winston S. Churchill.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.