Finest Hour 179

Cohen Corner

First American Edition

May 14, 2018

Finest Hour 179, Winter 2018

Page 34

Ronald I. Cohen MBE is author of A Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill, 3 vols. (2006).

It is hard to believe that, in a life rich with writings and crowned with the 1953 Nobel Prize for Literature, Churchill wrote so little autobiography. In a year in which he has been so present cinematically (two feature films—Churchill and Darkest Hour, an off-screen but strong presence in Dunkirk, and a significant role in the first series of The Crown), it seems appropriate to have a brief look at his sole autobiographical volume, My Early Life, which is also the only one of his books ever developed into a film, 1972’s Young Winston (see p. 10).

Churchill did write numerous autobiographical articles over the years—including, of course, the story of his escape from the Boers—that were published in periodicals such as Nash’s, the Strand, and Cosmopolitan. Seeking to gain additional income from the earliest of these, Churchill proposed in 1930 to use them in creating his first book since starting work on The World Crisis, four volumes of which had then been completed.

In February 1930, Churchill announced his projected autobiographical volume to his British publisher, Thornton Butterworth. He said that he wished to have the 50,000 words “in the articles I have already assembled” for My Early Life “set up in proof.” His demands were precise. “The book would vary from 100,000 to 125,000 words. It should be published at not less than a guinea. It could come out in the autumn publishing season of 1931.” In the end, Butterworth agreed with the typesetting proposal, and Churchill sent the first instalment off to Butler and Tanner, the printers, on 12 March. He was, as usual, enthusiastic about the content. “They [the old articles] seem to me to read extremely well and, when woven into the texture of a continuous narrative, they will I believe make a book of adventure, possibly of some permanent merit.”

2025 International Churchill Conference

Churchill next proposed that the publication date for the memoirs be advanced to the spring of 1931, putting off the last of the First World War volumes, The Eastern Front, until the autumn. “I feel ready to go on with these Memoirs now and my mind is full of ideas about them,” while, he explained, the last volume of The World Crisis “requires a great amount of new study and will gain if more time is taken over it.”

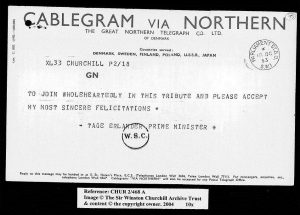

Once he had Butterworth’s approval regarding the revised publishing schedule, Churchill broached the idea of the book to Charles Scribner, his American publisher:

As you know, I have in the last five or six years written a series of articles on my past adventures, covering broadly speaking the first thirty years of my life. About 70,000 words…will be directly available for publication in book form. I shall write another 30 or 40,000 words so as to make a homogeneous narrative. This is easy for me as I have it all in my head….I think there is no doubt it will have wide popular value.

Churchill enclosed a synopsis and advised that the book would be a maximum of 110,000 words “of which perhaps 30,000 will be new material. I think myself it would have a very large sale as a book of real adventures, and of a young man’s struggle with life.”

Initially, Churchill anticipated that the “tale will end either in the year 1900 when I got into Parliament, or in the year 1905 when I first took office.” By 30 July he had changed his mind in this respect and, in fact, the book ended with these words: “Events were soon to arise in the fiscal sphere which were to plunge me into new struggles and absorb my thoughts and energies at least until September 1908, when I married and lived happily ever afterwards.”

By early August, Churchill’s secretary Violet Pearman sent Butler and Tanner “the last bundle of proofs” with the request that the printers return twelve copies of everything, which would “enable Mr Churchill to have twelve copies which he can circulate to various people before finally going into page proof. He would particularly like the proofs on Friday as he wishes to send one to America urgently.”

Churchill’s deal with the British publisher was attractive. Butterworth agreed to pay him a royalty of 25% to 5000 copies, 27½% over 7500 and 30% over 10,000. The final text was about 130,000 words, and Butterworth was torn between leaving the price at twenty-one shillings and raising it to twenty-five.

Churchill sent proofs of the volume around to some of his close friends and colleagues, including T. E. Shaw (better known as Lawrence of Arabia), Stanley Baldwin, and Lord Beaverbrook. Their comments were extremely favourable. To Baldwin, Churchill replied, in part, “I am hopeful that the book will do more than it was originally written to do, namely, to pay the Tax collector. There may even be a small surplus to nourish the author and his family.” David Lough’s thorough and entertaining tale of Churchill’s finances, No More Champagne, explains the interweaving of Churchill’s financial machinations, book contracts, and fiscal pressures.

Despite the wishful sentiment of the reviewer in The Times of 20 October, that “We can only hope that this autobiography is only an instalment,” this remained Churchill’s only purely autobiographical volume. Revelations of Churchill’s wish to continue the autobiography can be found from time to time in his letters. In one, shortly after he agreed to write a serialised Life for Lord Riddell in the News of the World (see C460a), he said to Thornton Butterworth:

I have undertaken to write for Newnes a short autobiographical sketch amounting to 35,000 words, from the standpoint of my sixtieth birthday (now impending), to be published in News of the World during the first quarter of next year. This has turned my mind to the continuation of my autobiography which I imagine has three more volumes. This I hope you will do for me when the time comes.

In December of that year, Major Pollock, manager of the Book Department at George Newnes Limited, had proposed a work to Churchill to follow upon their successful publication of The Great War. In his letter of 5 January 1935 refusing that proposal for the time being, Churchill did reveal some of his intentions regarding his own autobiography. In that letter, he said: “It seems to me moreover that I might tell the history of this period more easily (and more attractively) as a continuance of my biography [sic], the first volume of which has been published as ‘My Early Life’. I have always had the intention of completing this volume by volume, and its publication in a serial form when sufficient material has accumulated would be a project which I should like to examine later on with you, if we are both still alive at that date.”

It never happened.

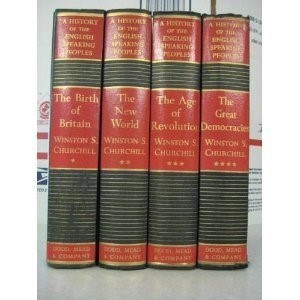

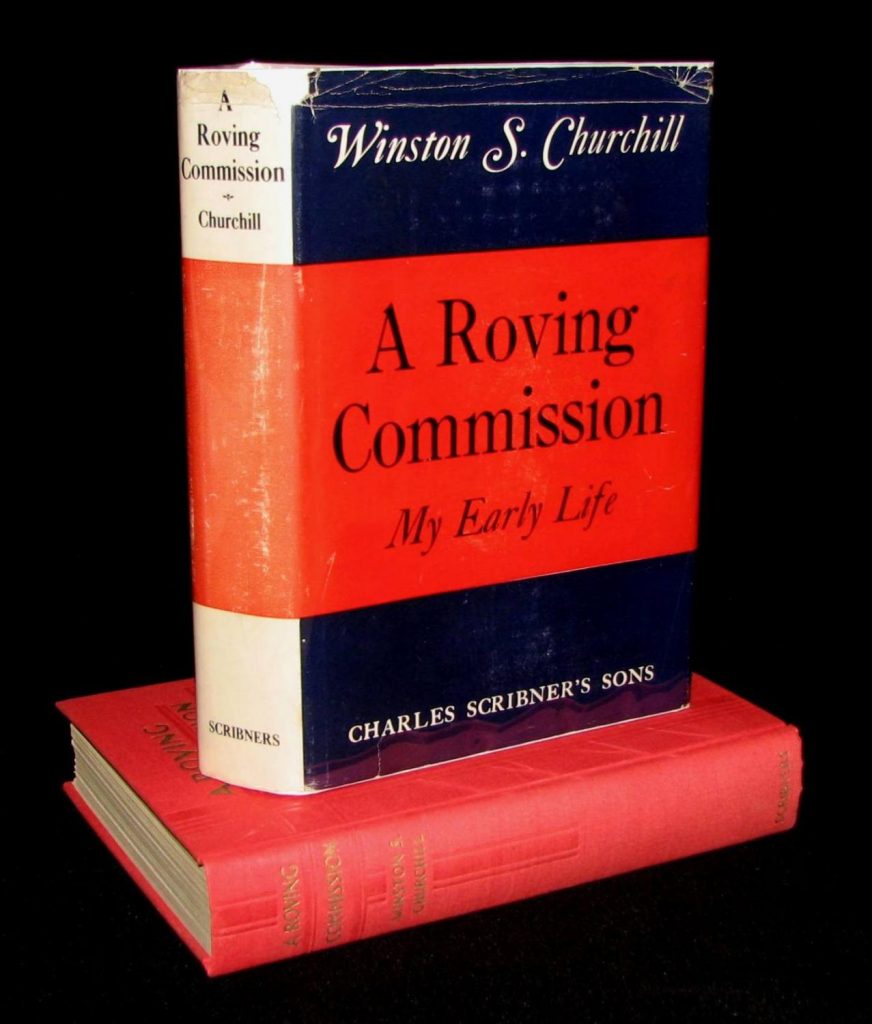

My Early Life has, however, been the most commercially successful single-volume work by Churchill. There are no fewer than twenty-three separate editions and issues in the English language, from the first British appearance on 20 October 1930 through the customarily beautiful Folio Society edition of 2007. The first American edition was published under the title A Roving Commission four days after the first British edition. Scribners has kept the autobiography in print longer than any other of its Churchill-authored titles after switching to the original British title in 1939. My Early Life has also been translated into eighteen languages, more than any other Churchill work except the Second World War.

Among the oddest of the English-language appearances is that published in Stockholm in 1936 by Albert Bonniers Förlag Svenska Bokförlaget, but there is none rarer than the Canadian Nelson “appearance” in 1930. I use that term advisedly since there never was a separate Canadian edition or issue. It cannot be identified by the volume itself (which is the Thornton Butterworth edition with strong, reddish-purple, calico-texture cloth) but only by the dust jacket, which is essentially the original British dust jacket modified to include the name of the Canadian distributor “Thomas Nelson and Sons, Ltd.” above that of “Thornton Butterworth” on the spine. Additionally, the Canadian price of $4.50 is printed on the front, the spine, and a rear panel. Only two such copies are known.

The popularity of My Early Life has led to numerous editions being produced. In Britain alone, there have been Keystone Library (1937–40) and Macmillan (1941– 44) issues, a British Reprint Society edition (1944), numerous printings of an Odhams edition in standard and deluxe bindings (1947–1965), thirteen printings of an Odhams School Edition (1958–64), eighteen printings of a Fontana paperback edition (1959–88), a new cased edition by Leo Cooper (1989), a Mandarin paperback issue, an Ulverscroft Large Print edition (1992), and an Eland paperback in 2000.

It would be fair to say that this charming, delightful, amusing, and informative autobiography is also extremely accessible. As of the date of this article, hundreds of copies of the book (in print or its audio CD version) are available online and elsewhere. It is hard to imagine a better entry-level introduction to Sir Winston.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.