Finest Hour 179

Books, Arts & Curiosities – Road to Hell

April 22, 2018

Finest Hour 179, Winter 2018

Page 45

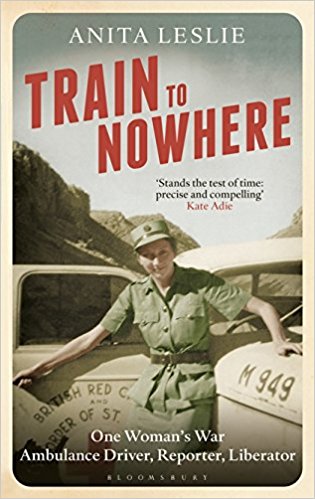

Anita Leslie, Train to Nowhere: One Woman’s War, Ambulance Driver, Reporter, Liberator, Bloomsbury Caravel, 2017, 336 pages, $20. 978-1448216680

Review by Celia Lee

Celia Lee is co-author with her husband John of Winston and Jack: The Churchill Brothers (2007).

First published in 1945, Anita Leslie’s Train to Nowhere enjoyed success, but, like other stories about the work carried out by women during wartime, it fast vanished into obscurity. In 2017, like a time capsule buried for seventy years, this gem has been rediscovered. Prepare to have demolished all your illusions of angel-like girls wearing shining white nurses’ uniforms and nun-like head-dresses. When you take up Train to Nowhere, you will find that The Road to Hell would have been a more fitting title.

Anita Leslie, cousin to Winston Churchill and from a genteel background of titled gentry living in an Anglo-Irish castle in Ireland, plunged head-first into war work by becoming a female ambulance driver in 1940. She worked first for the Motor Transport Corps (MTC) and then the Free French Forces, serving in Libya, Syria, Palestine, Italy, France, and Germany.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Well into the war, and having gained a great deal of experience with the British Army, Anita wanted to delve further and so became an ambulance driver in the French Army. If it was to be at the centre of more action she wanted, she certainly got it! She was sent to Naples and attached to a barracks at Pozzuoli. Wrapped in blankets, she slept her first night on a floor coated in insect powder.

After their ambulances arrived off another ship, the female drivers moved northwards, hoping to catch up with the French Army, which was chasing the Germans up the Rhone. They parked their ambulances in a row on a deserted racecourse beside Aix-en-Provence, where the men of the Company set up a field-kitchen. When evening came, they went to sleep in their ambulances. They pushed stretchers into the slots, and, when required, several nurses could sleep in these conditions in one ambulance.

Anita was posted to Combat Command 1 of the 1st Armoured Division, which was fighting in the mountains forty miles north of Besançon. She set off in search of Combat Command 1 as the French were fighting one of the hardest battles in their history. Anita was assigned to the unit of Jeanne de l’Espée, daughter of a famous French general. She caught up with Jeanne’s unit near a small village called Rupt, where Jeanne described to her the ambulance system. When the division went into action, the girls were posted to the regimental doctors and worked under their direct command, driving the wounded back from the regimental aid posts. Jeanne told her, “Now we are in full attack, and the girls are driving day and night and getting short of sleep, so you must begin work tomorrow.”

When more girls arrived to park their ambulances and snatch a few hours’ sleep, Jeanne advised Anita, “You see the girls have been taught to spend every possible moment sleeping, and you must learn to do the same. We eat well whenever we can, and whatever happens, remember to use lipstick because it cheers the wounded.” Anita soon learned that behind Jeanne’s humour “lay a character of steel.” The first soldiers Anita talked to told her that the previous Sunday Jeanne had driven out at nightfall and managed to rescue wounded parachutists from a mountaintop, where they had lain for three days surrounded by Germans. The enemy saw her driving up the rough track and opened heavy shell fire as she came down, but they missed.

When not driving, Anita and the other female drivers watched from their ambulances the traffic of war rushing to and fro. Files of French infantry trudged up to attack along the right-hand side, while the wounded came down on the left. Many of the Moroccan soldiers marched down from the front lines with bare or bandaged frost-bitten feet, carrying their wet boots as if the pain were more endurable that way.

Anita was reputed to be able to drive anything on wheels, and, when given her own ambulance to drive, it was one that had been captured from the Germans. It had a worn-out battery and unpredictable petrol pump far beyond even her technical capacity. Jeanne installed her office in it so that she could crouch out of the rain and check the whereabouts of her twelve-ambulance fleet. At night Anita and Jeanne shared it as sleeping quarters with stretchers as beds. They struggled out of their muddy boots and wet clothes, pulled off their men’s underwear, and wriggled into flea-bags. Jennie would say: “What on earth made us go in for this?” Train to Nowhere is an inspiring reminder of the hardship and heroism that saved the world.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.