Finest Hour 179

Books, Arts & Curiosities – Fine Furnishing

May 6, 2018

Finest Hour 179, Winter 2018

Page 43

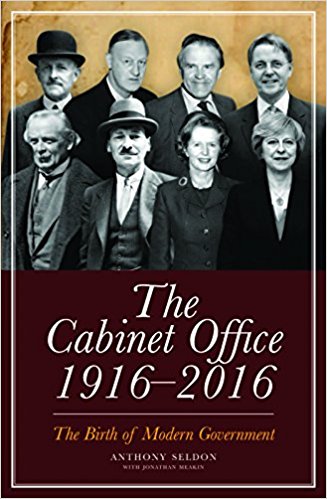

Anthony Seldon with Jonathan Meakin, The Cabinet Office 1916–2016: The Birth of Modern Government, Biteback, 2016, 360 pages, £25. ISBN 978–12785901737

Review by Iain Carter

Iain Carter is Political Director of the Conservative Party. He was previously a special adviser to the Leader of the House of Lords in the Cabinet Office.

Modern government can be traced back to the founding of the Cabinet Office in December 1916. Since then “its role as the central coordinator of government policy and its implementation remains essentially unchanged,” according to the current Cabinet Secretary, Sir Jeremy Heywood. Yet, despite being at the heart of almost all major decisions taken by the British government in the past century, the department remains something of a mystery even to experienced Whitehall operators.

Anthony Seldon’s The Cabinet Office 1916–2016 chronicles how the modest-sounding task of taking and distributing cabinet minutes grew into this crucial co-ordinating role. In doing so, it lifts the lid on this little-understood corner of government. It also offers a canter through twentieth-century British political history via the relationship between the Prime Ministers and their most senior official, the Cabinet Secretary.

After devoting the opening chapter to describing the emergence of cabinet government from the early modern period onwards, Seldon focuses on the eleven men who have led the Cabinet Office, beginning with Maurice Hankey, who was tasked with its creation under Lloyd George, and concluding with the current incumbent.

As would be expected from any work dealing predominantly with twentieth-century history, Winston Churchill is afforded a substantial role. Churchill was thought to be sceptical of the Cabinet Secretary when he rejoined the government at the beginning of the Second World War. Indeed, at a meeting of the War Cabinet in 1939 he told Edward Bridges he was running little more than “a magazine.”

Yet, despite the initial scepticism, Bridges became a vital source of advice during the war. Whilst Churchill relied heavily on General Ismay as his Chief Military Adviser—a role that perhaps foreshadowed the creation of a National Security Adviser in David Cameron’s No. 10—the contribution of Bridges in the civil sphere was indispensable. Although Bridges never lost his professional distance, his role as a ceremonial pallbearer at Churchill’s funeral in 1965 indicates just how important he became. It is this, which is explored by Seldon, not least through a discussion of the most significant of Churchill’s War Cabinet meetings from amongst the 919 which were supported by Bridges and his team.

On Churchill’s return to the premiership in 1951, he demanded that Norman Brook—Bridges’ successor as Cabinet Secretary, who himself was due to move on—remain in post. Churchill had a high opinion of Brook from an earlier spell in the Cabinet Office during the Second World War, had also kept in touch with him during the preparation of his memoirs, and went on to enjoy a closer personal relationship than the strictly professional one he had with Bridges. Seldon off ers an insight into how a civil servant, having grown personally as well as professionally close to his principal, went above and beyond, especially following Churchill’s stroke in 1953.

Later chapters, covering the Thatcher to Brown governments, have a different tone, offering something akin to a firsthand account of contemporary British political history as seen through the eyes of the most senior mandarins. Seldon draws on interviews with the living former cabinet secretaries, notably Lord Butler of Brockwell, who served Thatcher, Major, and Blair, and whose contribution feels particularly substantial. This is something that is lacking from earlier periods, where some officials kept no personal papers and offered no later account before their death. The coverage of the Cameron Coalition and later Conservative government feels more superficial, unsurprisingly, as many of those in question remain active in public life.

Running though the book are two recurrent themes. The first is the ability of the Cabinet Office to adapt to the needs of successive prime ministers without the creation of a true standalone Prime Minister’s Department. For example, the Cabinet Office worked with Lloyd George’s Garden Suburb; the Central Policy Review Staff (CPRS) favoured by Heath, Wilson, and Callaghan; and Blair’s Delivery Unit. The second is the sustained role of officials in promoting the cabinet and cabinet committees as their preferred forum for political decision making, albeit with an ebb and flow in their success.

Whilst this book is unlikely to reach as wide an audience as Seldon’s biographies of recent prime ministers—most notably Cameron at 10, Brown at 10, Blair Unbound, and Major—it nonetheless represents an excellent examination of this vital part of the Whitehall machine. Those wanting to understand how government operates and how officials and their political leaders interact will struggle to find a better study.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.