Finest Hour 178

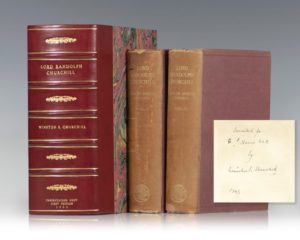

Cohen Corner – Churchill and Savrola

George Newnes edn., 1908

March 24, 2018

Finest Hour 178, Fall 2018

Page 38

Ronald I. Cohen MBE is author of A Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill (2006).

I was recently asked when Churchill’s only fulllength work of fiction was written, relative to its publication date. After all, most of the time (but not always), he chose his book subject and drove it forward to conclusion. That said, in later years, financial demands became a primary motivation, and the order of writing books occasionally changed as a function of publishers’ advances against royalties.

In the earliest days of his writing career, when his military histories and then his political perspectives and positions were paramount, Churchill wrote and published in order, except in the case of his only novel Savrola, about which he “misled” us in My Early Life regarding two not insignificant matters: his own attitude toward the book and the history of its creation.

In 1930, Churchill advised readers of My Early Life that, over the years he “consistently urged [his] friends to abstain from reading it [Savrola].” Although he stated that his attitude toward the work had not significantly mollified over the half-century between the publication of its first and second American editions, our acceptance today of this amusingly self-deprecating sentiment does not actually gibe with his expressed feelings at the time of writing and publication of the first edition. By way of comparison, consider the cautious restraint of his new foreword to the Random House republication in 1956, referring to the preface more than a half-century before: “The preface to the first edition in 1900 submitted the book ‘with considerable trepidation to the judgement or clemency of the public.’ The intervening fifty-five years have somewhat dulled though certainly not changed my sentiments on this point.”

Consider also the following from an interview with a reporter from The Toronto Daily Star in 1929: “‘Do you ever think, Mr. Churchill, of writing fiction?’ ‘Not much—I wrote a novel once.’ ‘What happened to it?’ ‘I don’t know,’ in the tone of voice people employ when they say ‘lost at sea.’”

While writing the novel, though, Churchill expressed a youthfully enthusiastic attitude: “It is far and away the best thing that I have ever done,” he wrote his mother on 24 August 1897. Nine months later, he said to Lady Randolph, “It is a wild and daring book tilting recklessly here and there and written with no purpose whatever, but to amuse. This I believe it will do. I have faith in my pen.” Soon after, he wrote his Aunt Leonie that the book “appeals to all tastes from philosophical to bloodthirsty and is full of wild adventures and atheistic philosophy.” This contrasts markedly with the perspective he expressed more than thirty years later in My Early Life.

As for the publication timeline, although Savrola is Churchill’s third published book, it was the first book he undertook and the second he completed. It was indeed already about one-quarter completed (he had written eighty pages or five chapters by the end of August 1897) when he set it aside on his return to Bangalore that month to begin work on The Story of the Malakand Field Force. On 29 August, he wrote: “The novel is indefinitely shelved. Five chapters are already completed and I am very much pleased with them. I hope before Christmas to have it ready for publication.” Churchill was unduly optimistic; it was, in fact, almost two years before the work appeared in volume form.

Churchill did return to the novel before submitting the Malakand text, and by 25 October eight chapters had been completed. On 24 November, when he was still six weeks away from sending on the Malakand manuscript, he remained consumed by Savrola. “[T]he novel filled & still fills my mind,” he wrote Lady Randolph. By 2 December, however, he was quite discouraged. He admitted to his mother then that “[t]he novel is at present illegible and must be shelved. I will have it typewritten as soon as possible and send it to you—in part—for your opinion. But you must remember it is in the rough and must be expanded.”

On 5 January 1898, he still had not returned to Savrola, although he had shipped off the Malakand manuscript on 31 December. He had, he said, “some reading to do which I intend to plod through before taking to the pen again.” Exactly three weeks later, he regretted that he still had not returned to his writing: “I am still reading—though I should prefer to write. The novel lies still unfinished and I am longing to take up the threads.” Churchill seemed more sanguine about the delay and, on 9 February, wrote Lady Randolph that “I am still reading a good deal and the novel remains half finished. But there is no hurry about it and as I have put & am trying to develop in the mouth of my hero a cheery but I believe a true philosophy it takes much thought.”

By 25 February, his former positive attitude was returning and he reported that “the novel is forging slowly along, and I like it better every day,” and, in a letter of 18 March, he declared his intention “to polish it until it glitters.” On 25 April, he believed that Savrola was within a chapter of completion and about four weeks from despatch. Indeed, on 3 May, maintaining that schedule, he still expected that the novel would be sent in a fortnight. Churchill’s estimates were a trifle optimistic; on 10 May, he reported that he would send off the first six chapters to his mother, although he was delaying completion because of some dissatisfaction with the ending, “[I]t rather falls away at present.”

By 16 May, the moment had arrived, in part. He despatched the Preface, Table of Contents, and six chapters, with the promise that the balance of the twenty (then projected) would flow at three per week, such that Lady Randolph would have the whole manuscript in a month. In his letter of 22 May, he announced that ten more chapters were going “by this week’s mail” and that the “remaining six” would go next week. Yet he wrote his brother Jack on 26 May that the novel was finished and that he had sent “5 chapters last week & 10 go by this mail: The other seven next.” On 1 June, he explained that the structure of the novel had changed somewhat, “making a total of 22 [chapters]. The last seven chapters are rather differently arranged to what I had originally intended.” The next day he actually sent off the remaining chapters, the necessarily altered Table of Contents, and a “list of suggested illustrations.”

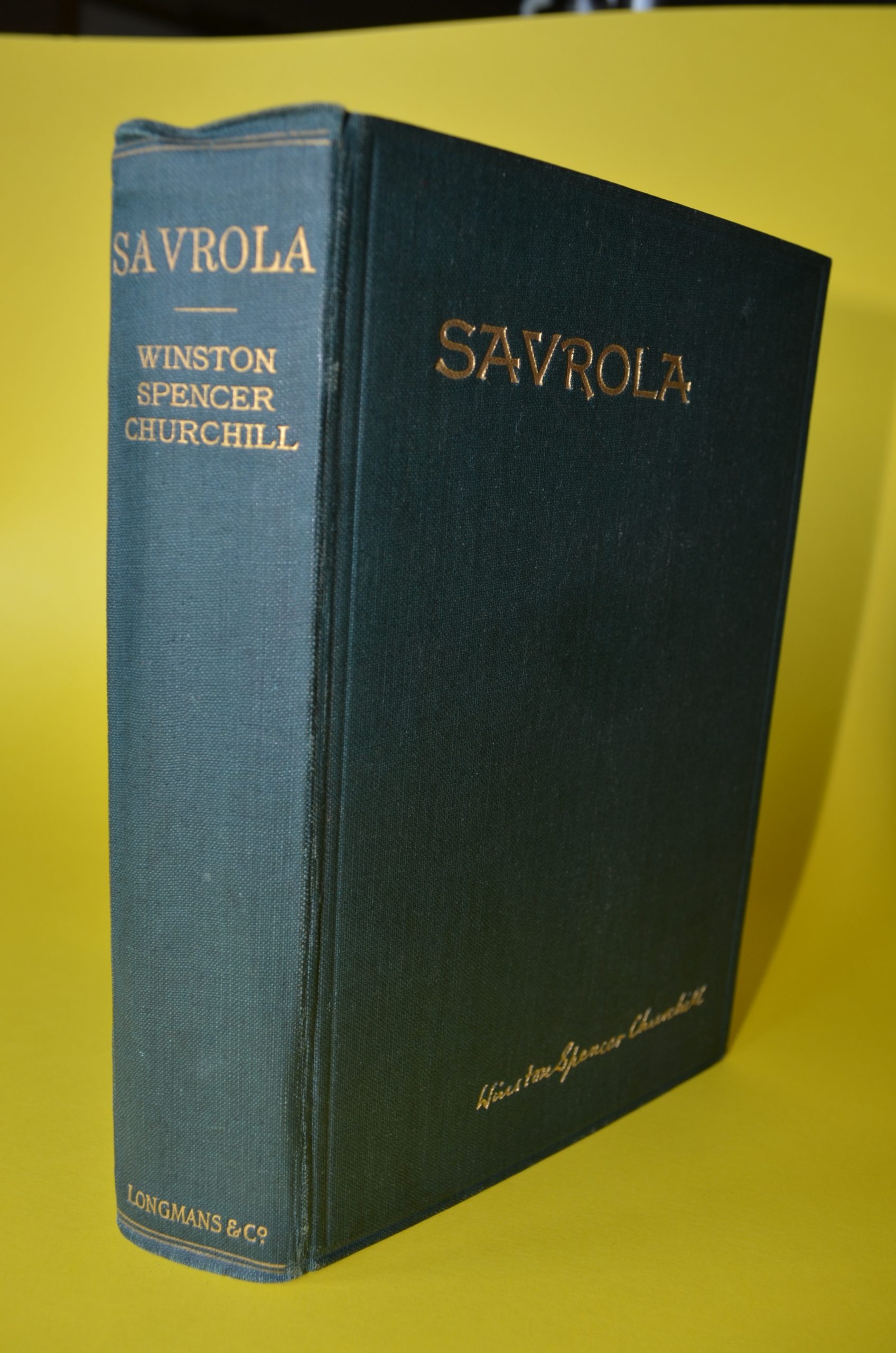

The book was done, but, although begun first it was published third, having been bypassed by The Story of the Malakand Field Force (14 March 1898) and The River War (6 November 1899). The Longmans agreement had been signed on 17 March 1899, and the novel was serialised in Macmillans Magazine from May through December 1899. Savrola was first published in Boston on 1 or 2 February 1900 (the publisher’s dates on the title page verso are incorrect). The English edition was published on 12 February 1900.

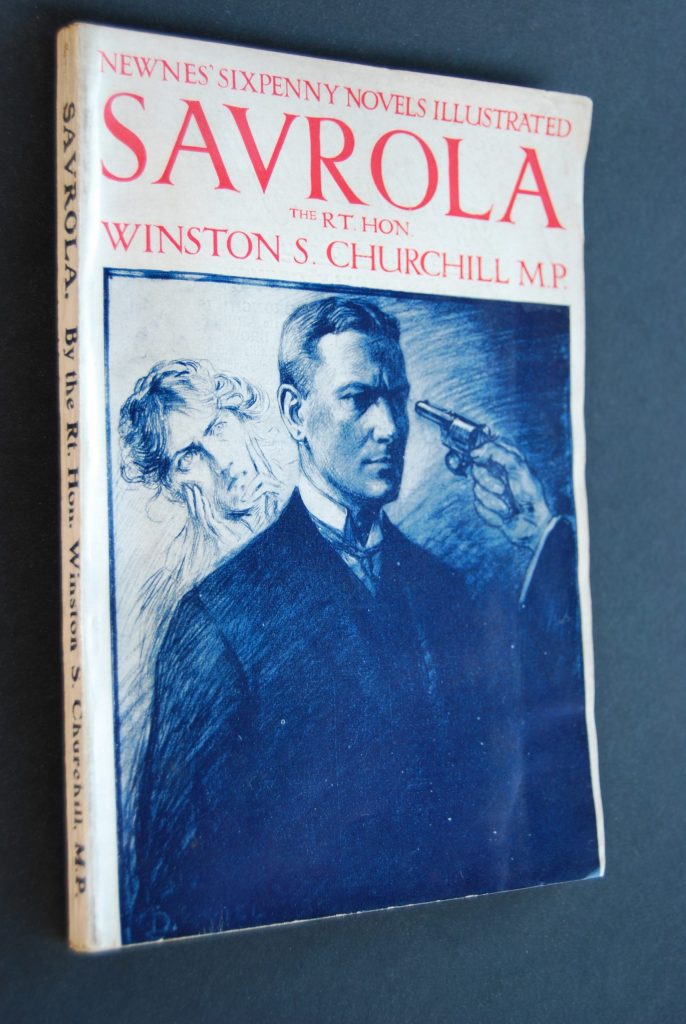

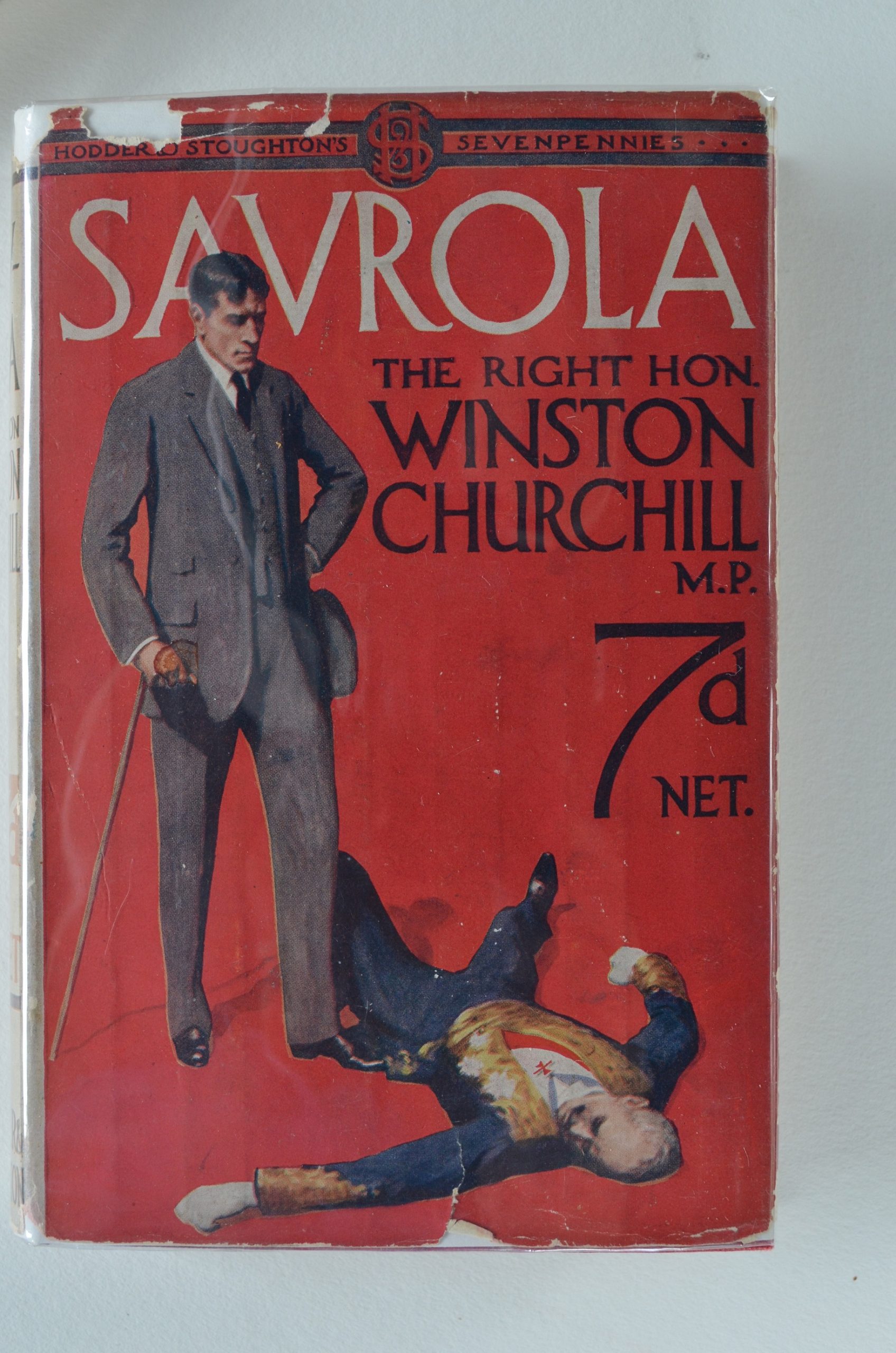

Thereafter, a beautiful paper wraps edition was published by George Newnes in 1908, a third edition by Hodder & Stoughton in their Sevenpenny Library in 1915, the American Random House edition in 1956, a UK Beacon Books paperback in 1957, a Cedric Chivers edition in 1973, Amereon House in 1976, and finally Leo Cooper in London in 1990. Interestingly, it was the very first of Churchill’s works to be published in translation (as Kansa Nousee in Hämeenlinna, Finland in 1916) and— just months ago—the most recent as Саврола (Savrola) in Kiev, Ukraine. It was also the most magnificent illustrated publication of any of Churchill’s volumes as published by À la Voile Latine in Monaco in 1950.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.