Finest Hour 178

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – Outfoxing the Holy Fox

January 13, 2018

Finest Hour 178, Fall 2018

Page 43

Review by Michael McMenamin

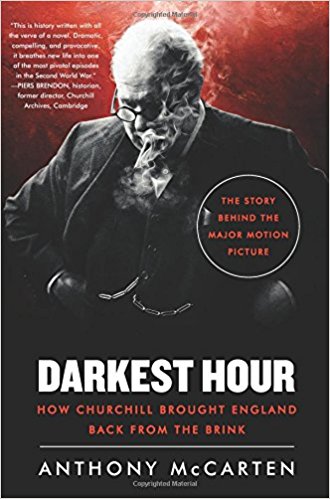

Anthony McCarten, Darkest Hour: How Churchill Brought England Back from the Brink, Harper Collins, 2017, 336 pages, $16.99. ISBN 978–0062749529

Michael McMenamin writes the “Action This Day” column. He is co-author of Becoming Winston Churchill, the Untold Story of Young Winston and His American Mentor (2007).

Anthony McCarten, the screenwriter of the film Darkest Hour, has written a book about the time when Churchill became Prime Minister on 10 May 1940 through the miracle of Dunkirk on 4 June. There is a special focus on War Cabinet meetings in late May, when a politically weak Churchill outmaneuvered his own Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax (known as the “Holy Fox”), who wanted to have Mussolini ascertain Hitler’s peace terms.

2024 International Churchill Conference

McCarten wrote the book after writing the screenplay because, according to his publicist, “he had more to say about the subject than the film allowed.” The book tells a gripping, albeit oft-told story. But the “more to say” that is accurate is not new, and what is new is not accurate.

McCarten writes that “Many readers will be astonished to learn that the great Winston Churchill… told…the War Cabinet that he would not object in principle to peace talks with Germany ‘if Herr Hitler was prepared to make peace on the terms of the restoration of German colonies and the overlordship of Central Europe.’” Yet Churchill’s “overlordship” statement has been published in many books through the years.

What is new here is McCarten’s claim that between 13 and 28 May, Churchill changed his position from “victory at all costs” to “seriously considering…peace talks” back to “choking in his own blood” rather than “consider negotiations with That Man.” McCarten says this “puts me at odds with almost all the historians” who have taken a contrary view.

McCarten’s argument that Churchill “seriously considered” peace talks with Hitler is unpersuasive. It relies mostly on War Cabinet minutes where Halifax argued for and Churchill against seeking Hitler’s peace terms. There, the two men debated hypotheticals as to what Germany might offer and what Churchill might accept, not actual peace terms. McCarten makes too big a meal of this claiming the minutes show that Churchill “seriously consider[ed] peace talks with Hitler,” but Churchill’s words can plainly be read as arguments against seeking terms. Furthermore, McCarten fails to explain why Churchill suddenly returned to his original position. He just says that Churchill did so right before his 28 May meeting with the outer Cabinet. In the film, he creates a fanciful explanation.

McCarten summarizes his case in an epilogue, but it remains unpersuasive:

No, those who disagree with McCarten on this do not have to “posit a near-unhinged Churchill, a man utterly immune to the terrifying facts on the ground and amnesiac about his own tragic miscalculations at Gallipoli” and Norway.

No, Churchill did not consider Gallipoli “his own tragic miscalculation” nor were there “dark lessons he learned about himself from Gallipoli [that] never left him.” In 1915 as in 1940, he thought it to be a strategy far superior to the senseless trench warfare of Europe.

No, Churchill would not have been “insane,” as McCarten claims, not to “seriously consider peace talks in preference to almost certain annihilation,” because Churchill knew the RAF and the Royal Navy posed almost insurmountable obstacles to a successful German invasion of Britain.

No, Churchill was not “gradually persuaded that, so long as British independence was assured, it made sense to seriously explore peace with Nazi Germany.” Rather, Churchill said in a War Cabinet meeting on 26 May “we could never accept” a peace “achieved under a German domination of Europe.”

McCarten covers Churchill’s life before May 1940 in a captious chapter portraying his subject as going from one failure and misjudgment to another—the standard anti-Churchill charges. Just skip it and go straight to the good parts like this fictional exchange between Halifax and Churchill, where McCarten imagines him explaining to Halifax “that you can’t reason with a tiger when your head is in its mouth!” Priceless. Despite the flaws, you will enjoy the book. It is an inspiring end.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.