Finest Hour 176

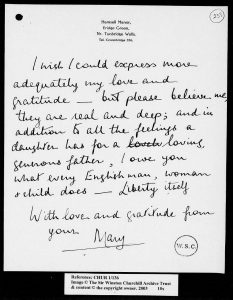

A Conspicuous Failure: Lord Randolph Churchill

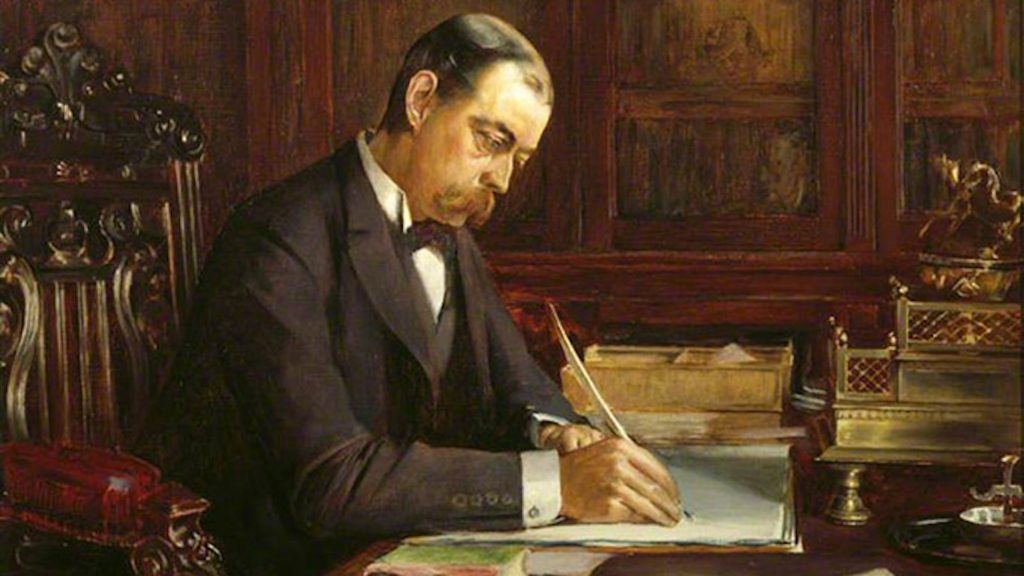

Lord Randolph Churchill © National Trust, Chartwell; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

September 12, 2017

Finest Hour 176, Spring 2017

Page 14

By Paul Addison

Lord Randolph Churchill ’s life has long been over-shadowed by the enduring fame of his son. By comparison with Winston’s heroic feats as a war leader, the father’s political career was brief, embedded in the obscure and long-forgotten politics of late Victorian Britain, and a conspicuous failure. It is no surprise, therefore, that he attracts comparatively little attention, but in one respect, at least, the situation fails to do him justice. Winston Churchill was, in more ways than one, his father’s creation.

Randolph Churchill (1849–1895) was the second surviving son of the seventh Duke of Marlborough. After Eton, and Magdalen College Oxford, where he obtained a respectable degree in law and history, he devoted most of his time to fox hunting. In 1874 he was elected to the House of Commons as the Conservative MP for Woodstock, a small country town at the gates of Blenheim Palace, where the duke’s influence over the electors virtually guaranteed his victory. Randolph contested the seat partly from loyalty to his family, and partly in return for his father’s permission to marry Jennie Jerome, a match of which he initially disapproved. As yet he gave no sign of ambition and neglected politics in favour of high society. He and Jennie were a dazzling young couple at the heart of the “Marlborough House Set,” the favourite friends and companions of “Bertie,” the philandering Prince of Wales.

In 1876 a scandal plunged Randolph into conflict with “Bertie.” The Earl of Aylesford, a companion of the Prince, planned to divorce his wife on the grounds that she had committed adultery with Randolph’s elder brother, the Marquess of Blandford. In an attempt to prevent the scandal from becoming public, Randolph threatened to produce compromising letters the Prince had written to Lady Aylesford some years before. It was a daring move, driven by ferocious loyalty to the good name of the Churchills. Aylesford dropped the divorce proceedings, but the Prince was furious and instructed his friends to ostracise Randolph, in effect banishing him from high society. For the next eight years, until a reconciliation occurred, Randolph lived under the shadow of royal displeasure. “In the interval,” wrote Winston in his father’s biography, “a nature originally genial and gay contracted a stern and bitter quality, a harsh contempt for what is called ‘Society’, and an abiding antagonism to rank and authority.”1

In order to defuse the tensions, Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli appointed the duke Lord Lieutenant (“Viceroy”) of Ireland, and the Churchills moved to Dublin with Randolph as his father’s unpaid private secretary. John Winston Spencer Churchill, the seventh Duke of Marlborough (1822–1883), was a leading Conservative and devout Anglican who took the problems of Ireland seriously. Randolph, who accompanied his father on his travels around the country, got to know Catholics as well as Protestants, and Nationalists as well as Unionists. Of all his contacts, however, the most important was the chief legal adviser to the Irish government, Gerald Fitzgibbon, who became a lifelong friend. Randolph’s ideas on Ireland owed much to Fitzgibbon and the circle of enlightened unionists around him. While strongly opposed to nationalism, they sought to address Irish grievances through reforms in education and land tenure, and the cementing of an alliance between the Tory Party and the Roman Catholic Church.

Return to Westminster

When the Conservatives were defeated in the general election of 1880, the Liberals took office under Gladstone, and the duke and his family returned to England. For the next four years, however, the doors of high society remained closed to Randolph and Jennie, a humiliation that helps to account for the unmistakable undercurrent of anger and aggression in his politics. With two other Tory malcontents, Henry Drummond-Wolff and John Gorst, and some assistance from Arthur Balfour, he formed a rebel group dubbed by contemporaries “the Fourth Party.” (The other three were the Tories, the Liberals, and the Irish.) The Fourth Party pursued a dual strategy of harassing and obstructing Gladstone while undermining and attacking their own party leaders, Lord Salisbury in the House of Lords and Sir Stafford Northcote in the House of Commons. Were they, perhaps, secretly colluding with Salisbury against Northcote? MPs debated grave issues in grave tones, but parliamentary politics were overlaid by intrigues and rivalries in which all the leading figures were jockeying for position, with Randolph setting a cracking pace.2

In 1880 Randolph was a comparatively obscure backbench MP. By 1886 he was Chancellor of the Exchequer and heir apparent to Salisbury as Prime Minister. On the high wire of politics, he was a supreme acrobat whose feats of daring were as breathtaking as they were unpredictable. Sometimes he spoke as a dyed-in-the-wool Tory, defending the powers of the House of Lords or demanding protective tariffs as the only salvation for British industry. Sometime he attacked the Gladstone government from the left, deploring military spending or the occupation of Egypt as vigorously as any Radical. He also claimed to stand for Tory Democracy, a phrase borrowed from Disraeli. On one occasion he declared himself in favour of the kind of “Tory Socialism” introduced by Bismarck in Germany. On another he equated Tory Democracy simply with popular support for the monarchy and the constitution. When asked what it meant he replied: “To tell the truth I don’t know myself what Tory Democracy is, but I believe it to be principally opportunism.”3

Randolph was, however, a true pioneer of the politics of mass democracy. In the mid-nineteenth century the Tories had been a party based mainly on the Church, the Land, and pockets of commercial wealth. With the extension of the franchise and the continuing expansion of towns and cities, they needed politicians who could win support for the party in hitherto alien territory. Randolph was not alone in seeing the need to broaden the party’s base, but he was by far the most successful in reaching out beyond suburbia to the urban working class. (Agricultural labourers, he claimed, were not intelligent enough to deserve the vote.) With his protuberant eyes, rakish moustache, and dandified dress, he was a cross between a charismatic orator and a music-hall turn. His speeches, which he delivered in advance to the press, were a blend of vacuous rhetoric, political polemic, and personal abuse, seasoned with humour and wit. The speech in which he mocked Gladstone over his favourite recreation of felling trees on his estate (“the forest laments, in order that Mr Gladstone may perspire”) was a satirical masterpiece.4

“Ulster Will Fight”

I n the House of Commons one of his greatest assets was his knowledge of Ireland, on which he was an acknowledged authority. By 1881 the Irish countryside was the scene of a campaign of intimation and terror against landlords waged by the Land League—of which the president was Charles Stewart Parnell, the leader of the Irish party at Westminster. At first Gladstone responded with coercive measures, including the mass internment of Land Leaguers and the imprisonment of Parnell himself in Kilmainham Gaol. When he struck a deal with Parnell to defuse hostilities on both sides, and released him from prison, Randolph denounced the “Kilmainham Treaty” as a surrender to terrorism. Subsequently, however, he struck up a close relationship with Parnell—a land-owning squire who loved hunting and cricket—on the ground that he was fundamentally a conservative in harmony with Tory views. In 1885 they colluded in bringing about the defeat of Gladstone in the House of Commons. During the short-lived Conservative government that followed, Randolph persuaded Parnell that the Irish would get a better deal from the Tories than they would from the Liberals, and Parnell for his part urged all Irishmen in Britain to vote Conservative in the general election of December 1885. Had the tactic succeeded, and the Conservatives won the election, Churchill and Parnell might have worked out some kind of deal, but it seems unlikely that Randolph would have conceded Home Rule, a policy anathema to most Tories, and indeed to his friends in Dublin.

When Gladstone returned as Prime Minister he announced his conversion to Home Rule, split his own party in two, and set in motion a ferocious struggle between the Protestants of Ulster, where popular resistance to “Rome Rule” was mobilised by the Orange Order, and the Roman Catholics of the south, most of whom were Nationalists. Randolph fanned the flames of the Protestant revolt. As he explained to Fitzgibbon: “I decided some time ago that if the G.O.M. [“Grand Old Man,” i.e., Gladstone] went for home rule, the Orange card would be the one to play. Please God it may turn out the ace of trumps not the two.” Later he appeared to incite armed resistance to Home Rule in a public letter: “Ulster will fight, Ulster will be right.”5 In defence of Lord Randolph it can be urged that what he said was true and even prophetic. Protestant Ulster was prepared to resist Home Rule by force if necessary. He could also lay claim, through his mother Frances, Duchess of Marlborough, to Ulster Protestant ancestry. By his own confession, however, his sword-rattling, which taken literally verged on treason, was merely a ploy to bring down Gladstone.

Immolation

Such was Churchill’s pre-eminence that when the Tories returned to office in July 1886, Salisbury appointed him Chancellor of the Exchequer. Salisbury, however, feared that his finance minister lacked judgment, as indeed he did. After ditching protectionism in favour of free trade, he drew up a set of budget proposals based on the classic Gladstonian principles of “peace, retrenchment and reform.” They included, however, substantial cuts in the defence estimates that ran into strong resistance in the Cabinet. In an effort to force the Prime Minister’s hand, he offered his resignation in the expectation of triggering a crisis from which he would emerge victorious. Salisbury, however, called his bluff, accepted the resignation, and appointed George Goschen in his place. Randolph battled on in the political wilderness for another eight years and would almost certainly have been re-admitted to the fold if he had lived, but he died in January 1895, after a long illness in the course of which he slowly and agonisingly lost the power of speech. It has often been claimed that he died of syphilis, but Dr. John Mather, a historian of medicine, argues persuasively that Randolph’s symptoms could well have been caused by a brain tumour.6 Nor, despite gossip and speculation, do we know anything for certain of Randolph’s private life outside his marriage.

His most important legacy was his son Winston, whose early career was virtually a continuation of his father’s. With the help of his mother, Lady Randolph, he exploited his father’s political contacts. He imitated his speeches and adopted his rallying cry of Tory Democracy. In the House of Commons he declared that he had come to “pick up the tattered flag” of his father’s proposals in the budget of 1886. The “Hughligans,” a group of backbench rebels to which Churchill belonged with his great friend Hugh Cecil, was highly reminiscent of the Fourth Party. Between 1902 and 1905 he wrote a two-volume life of his father that managed to be, at one and the same time, a work of filial piety and a major contribution to recent political history. As an ambitious young man, however, Churchill could not afford to shackle himself to the past. While paying homage to Lord Randolph, he was beginning to emerge from his father’s shadow by abandoning the Tories for the Liberals, a shift that involved the repudiation of a number of his father’s policies. It was not through his doctrines or policies that Randolph lived on in Winston, but through his character, temperament and political style.

GET OUR BULLETIN

The resemblances were noted by the Arabist and maverick Tory W. S. Blunt, who had known Randolph well. On meeting Winston for the first time in 1903 he wrote:

In mind and manner he is a strange replica of his father, with all his father’s suddenness and assurance, and I should say more than his father’s ability. There is just the same gaminerie and contempt of the conventional and the same engaging plain spokenness and readiness to understand. As I listened to him recounting conversations he had had with Chamberlain I seemed once more to be listening to Randolph on the subject of Northcote and Salisbury….In opposition Winston I expect to see playing precisely his father’s game, and I should not be surprised if he had his father’s success.7

Legacy

In his vaulting ambition, rousing platform oratory, love of bold initiatives, stubborn independence of judgment, abrupt changes of course, and readiness to shock and offend, Winston was in many ways a reincarnation of Lord Randolph, and the reactions of the political world were similar.

The brilliance of the performance propelled him to the top, but simultaneously gave rise to mistrust of his motives and doubts about his judgment. There were also, however, notable contrasts between father and son. Randolph lacked Winston’s romantic imperialism, his fascination with the conduct of war and his intermittent sense of destiny. Where Randolph was immersed in party politics, Winston struggled to break free of them. In writing his father’s life he had revisited every twist and turn of the Home Rule crisis of 1886. Perversely the effect had been to subordinate British parties to Irish quarrels, with the Liberals taken hostage by Irish Nationalists and the Tories by Ulster Unionists. By 1914 Ireland stood on the brink of a civil war that threatened to range the British parties on opposite sides. As a leading figure in the Liberal party Winston was compelled to play politics too, but his underlying aim was to bring about a cross-party agreement, and a compromise settlement in Ireland, that would remove the Irish question from British politics. The Irish Treaty of 1921, of which Winston was one of the authors, was the most authentic expression of his policies towards “John Bull’s Other Island.”

This brings us to what seems at first sight to be the most striking contrast between father and son. Randolph, unlike Winston, never graduated from politics—the art of winning and holding power—to statesmanship, the use of power for the greater good of a nation or, indeed, of the world. The judgment, however, is flawed. Randolph died at the age of forty-five after an exceptionally brief ministerial career. Winston was sixty-five, with a long and varied experience of high office behind him, before he became Prime Minister in 1940. Who can tell what Randolph might or might not have achieved in the space of another twenty or thirty years? Could it have been Randolph instead of Lloyd George who succeeded Asquith as Prime Minister in 1916? There is simply too little evidence to go on. Dying before his capacities as a statesman could ever be put to the test, he will always elude the judgment of historians.

Paul Addison is Honorary Fellow of the School of History, Architecture, and Classics at the University of Edinburgh. His books include Churchill on the Home Front (1992) and Churchill: The Unexpected Hero (2005).

Endnote

1. Winston S. Churchill, Lord Randolph Churchill (London: Odhams, 1952), p. 69.

2. While the biographies of Lord Randolph by his son (1906) and Robert Rhodes James (1959) both have great merit, the most thoroughly researched and penetrating analysis of his tactics is to be found in R. F. Foster, Lord Randolph Churchill: A Political Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981).

3. Foster, p. 165; Roland Quinault, “Lord Randolph Henry Spencer Churchill” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004); John Ramsden, An Appetite for Power: A New History of the Conservative Party (London: Harper Collins, 1998), p. 144.

4. Winston Churchill printed long extracts from the speech in Lord Randolph Churchill, pp. 221–24.

5. Ibid., pp. 446 and 450.

6. Dr. John H. Mather, “Lord Randolph Churchill: Maladies et Morte” in Finest Hour, winter 1996–97, pp. 23–28.

7. W. S. Blunt, My Diaries, Part Two, 1900 to 1914 (London: Martin Secker, 1920), p. 77.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.