Finest Hour 175

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – C’est beau, mais c’est faux

April 6, 2017

Finest Hour 175, Winter 2017

Page 45

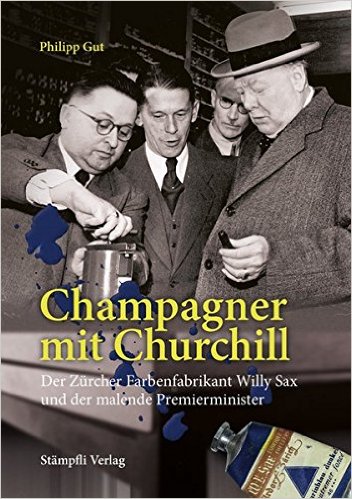

Philipp Gut, Champagner mit Churchill: Der Zürcher Farbenfabrikant Willy Sax und der malende Premierminister, Stämpfli Verlag, 2015, 176 pages, €39.00. ISBN 978–3727214554

Review by Werner Vogt

Werner Vogt is the author of Winston Churchill und die Schweiz reviewed in FH 173.

When Winston Churchill visited Switzerland in the summer of 1946, various remarkable things happened. With his “Let Europe Arise” speech, addressed to the academic youth of the world and delivered at the University of Zurich [see FH 173], the wartime Prime Minister and then Leader of the Opposition confirmed his position as a leader of thought. On the same day, Churchill invited Willy Sax to his hotel for a drink before dinner. Here was conversation more to Churchill’s liking, for Sax was the Swiss owner of the small paint factory that supplied Churchill’s needs. Churchill recognised that Sax had not only an excellent knowledge about the composition of his paints but also about mixing and painting techniques.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Out of this informal conversation developed a friendship that lasted nearly twenty years; Sax died less than a year before Churchill. Philipp Gut, who is a deputy editor of the staunchly Conservative magazine Die Weltwoche and a historian by training, gives a detailed account of Sax’s numerous journeys to Chartwell as well as to the South of France, whither Sax was repeatedly invited when Churchill went there for painting holidays.

It would not be fair to call the amity that evolved between Churchill and Sax a mere “functional” friendship. Too deep was Churchill’s appreciation for Sax, his wife and daughters, and above all for some of the fine Swiss painters, which Sax brought along on some of his visits with Churchill. One such was Cuno Amiet, one of the greatest Swiss painters of the twentieth century. When embarking on the journey to Chartwell, Amiet—an octogenarian who was not prone to strong drink—had his first whisky on the ferry to Dover just to make sure that he would be ready for the challenge if need should arise.

Gut proves to be a good raconteur of lovely anecdotes. Amiet, we learn, did not mince his words when confronted with Churchill’s paintings. When asked on one occasion in Southern France to comment on a particular canvas by Churchill, Aimet —conversing in French because Sax’s conversational English was insufficient—said: “C’est beau, mais c’est faux” (It’s beautiful, but wrong). Churchill took some time—and lunch—to digest the blow and eventually answered in his inimitable way: “You are right, Mr. Amiet, my truth is wrong, and your error is right.”

Gut’s narrative is based on Sax’s diary and correspondence with Churchill still in the family archives. He was helped as well by a booklet Sax’s daughter Maya compiled twenty years ago, which contained the main facts about the Churchill-Sax relationship, albeit in an amateur narrative. The result is a beautiful tale about a friendship founded in the sunset of two men’s lives. The simple tale of the Swiss entrepreneur enjoying excellent food and drink in abundance, discussing everything from strokes (Churchill), heart attacks (Sax), politics, and—above all—art, is a beautiful story.

There is, however, a huge discrepancy in the author’s treatment of Churchill and Sax. The reader learns nothing new about Churchill’s career, but the main facts are covered in sufficient detail. Yet on Willy Sax we learn surprisingly little. There is, of course, his date of birth and the mentioning of his hobbies: Sax was a talented musician (violin, piano, accordion) who even played in the Tonhalle orchestra in Zurich—the equivalent of London’s Royal Albert Hall or St. Martin-in-the-Fields. We learn also that Sax was a keen fisherman, who caught his fair share of pike and trout in the rivers near his home.

What we do not learn about Sax from Gut’s book are answers to questions like: How did his family business develop under his leadership? Where was he educated? When, where, and how did he take on Churchill as a client?

Most importantly, why did Gut not reveal that Sax was not so apolitical as claimed in Maya Sax’s booklet? Sax was in fact a National Front candidate in his hometown of Dietikon in 1934. He finished far behind the winners, but, at thirty-six, he was hardly an innocent. The National Front in Switzerland was a far-right movement, which was not so extreme or—as we now know—so dangerous as the Nazis in Germany. Nevertheless, the “Frontists,” as they were called, were by no means harmless. They were anti-Socialist, anti-liberal, and—above all—anti-Semitic. Some of their activists did condone and perpetrate political violence.

The behaviour of Sax could be explained as the foolish actions of someone with no gift for politics, but, unfortunately, this is not covered in the book. Painting the full picture of Sax’s pre-Churchill life rather than just a sketch would have made Gut’s book stronger and more honest.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.