Finest Hour 172

My Father’s Hero: John Wayne & Winston Churchill

June 12, 2016

Finest Hour 172, Spring 2016

Page 24

By Aissa Wayne

My father had two great heroes. One was John Ford, the legendary film director who propelled him into stardom. The other was Winston Churchill.

Due to his public image as a laconic cowboy, few people knew that my father enjoyed intellectual pastimes. He played chess extremely well, and he read avidly. For pure escape he favored mysteries: Agatha Christie, Rex Stout, and Raymond Chandler. He was also a fan of Ernest Hemingway.

Due to his public image as a laconic cowboy, few people knew that my father enjoyed intellectual pastimes. He played chess extremely well, and he read avidly. For pure escape he favored mysteries: Agatha Christie, Rex Stout, and Raymond Chandler. He was also a fan of Ernest Hemingway.

Besides Hemingway, mysteries, and novels he thought might translate well to the screen, my father stuck mostly to nonfiction: political histories, military biographies, and anything at all by Winston Churchill, the public figure he most revered. In a March 1971 interview with Playboy, when the questioner asked him who he would most like to spend time with, my father replied, “That’s easy: Winston Churchill. He’s the most terrific fella of our century….Churchill was unparalleled. Above all, he took a nearly beaten nation and kept their dignity for them.”

My father’s interest in Churchill began long before he spoke with Playboy. In the summer of 1951 he was on location in Ireland filming The Quiet Man, one of his most beloved classics. Andrew McLaglen—an assistant director on the film as well as the son of movie co-star Victor McLaglen, who played Squire Danaher—remembered seeing my father on the set reading Churchill’s war memoirs. Andrew did not recall which volume, but it may have been the fourth, The Hinge of Fate, which had been published in the United States the previous year but which was not yet available in Britain.

Two decades later, around the time the Playboy interview was published, my father was in New Mexico filming The Cowboys. He stayed in a rented home (his preferred accommodation when shooting on location), where he liked to mix up a chili soufflé in the kitchen and then go to bed early in order to read his way yet again through Churchill’s books.

2024 International Churchill Conference

As a young girl I knew little about Churchill since I was born after the war. I can remember, though, my father telling me about the Second World War and his admiration of Churchill’s doctrine of peace through strength. He could even quote Churchill’s writings from memory.

Three Connections

Although John Wayne and Winston Churchill never met or even exchanged letters, there were connecting threads between them. First, although my father did not know it, he was related to his hero three times over. As is well known to readers of Finest Hour, Churchill’s mother, Jennie Jerome, was American. The Jeromes were distantly related to the Morrisons. My father’s real last name was Morrison.

According to Gregory Smith, the leading authority on Churchill’s American ancestry, John Wayne and Winston Churchill share descent from three—unrelated—common American ancestors: Jonathan Murray, George Way, and Francis Sprague. By the closest of these relations, my father was a fifth cousin twice removed to his hero. Looking at it another way, I recently learned that I am an eighth cousin of Sir Winston’s great-grandson Randolph. I know this would have pleased my father more than anything.

The Family Jewels

Another connection binding the Wayne and Churchill families is that Sir Winston and I both featured on the cover of the March 1961 issue of Cosmopolitan. I was not even five years old when my father took me along on a business trip to New York, where we were both photographed for the magazine. Unlike my father, though, I was draped in jewelry.

The cover featured my smiling image over the caption, “John Wayne’s daughter, Aissa, and $850,000 in Cartier diamonds.” To the left of my picture, the cover boasted a line-up of authors contributing to the issue. At the top of the list was Winston Churchill. Further down was Ernest Hemingway. My father had hit the trifecta!

My father framed the cover and put it on the trophy wall of his office in our home. He would stop before it and say to me, “Your smile is brighter than any diamond, Aissa.” I am sure the Churchill connection also made him proud.

For those who are curious, the article by Churchill was a re-print of one that first appeared in Cosmopolitan thirty-five years before in 1926 called “I Ride My Hobby.” This story was included in the anthology Thoughts and Adventures (1932) and later combined with an essay on painting to produce Churchill’s short work Painting as a Pastime (1948).

The Alamo

A third connection between my father and Churchill is more tenuous and even a bit of a mystery. In 1960 my father released his film The Alamo. The project had been the greatest ambition of his career. He produced, directed, and starred in the movie and even invested almost every dollar our family had.

My father, however, did not think the film’s distributor, United Artists, would do enough to publicize the release. At his own expense he hired the legendary publicist Russell Birdwell, the same man who had run publicity for Gone with the Wind. Birdwell was not a man to let the truth get in the way of the claims he made on behalf of his clients.

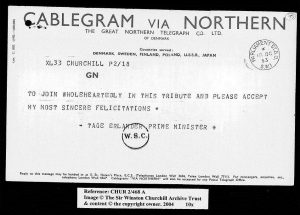

Putting together a souvenir program to be distributed with the film, Birdwell sought out contributions from famous people. A faded sender’s copy of the Western Union telegram that Birdwell sent to Churchill has survived. It reads in fractured syntax:

Dear Sir, As you may know by now John Wayne has produced and directed a twelve million dollar picture entitled The Alamo. Based upon the great chapter in Texas early history which was made possible by seventeen men from England who were among the 185 who fought to their deaths against the seven thousand enemy troops of General Santa Anna. We are planning to issue a souvenir program with great dignity with historic scenes, and Mr. Wayne and I would be most grateful if you would consider writing a hundred word forward [sic] for this book. We would be most happy to pay a fee to any charity that you would like to name. Few people know or remember that once, just 124 years ago, seventeen men came from your great country to take their stand at the Alamo to set an example and a pattern for free men everywhere. John Wayne and I would be most grateful if we might hear from you at your earliest convenience.

The telegram was sent to Churchill care of the House of Commons on 8 July 1960, but the Churchill Archives Center has no record of the communication. Certainly no reply from Churchill was ever received.

Of course, my father also received many such requests every day, and he always tried to answer each one personally even if it was with just a short note. Churchill, however, was eighty-five in 1960, and his secretary had to deal with all unsolicited communications, which frequently meant never showing them to the addressee. There is no mystery, then, as to why Churchill did not reply, but the fate of the intended recipient’s copy of the telegram remains unknown.

Go-to Men

My father made many films set during the Second World War. Most of them were fictional stories, but The Longest Day depicted actual events from the D-Day landings with which Churchill was so closely connected. Dad played a reallife hero, Benjamin Vandervoort, a lieutenant colonel in the 82nd Airborne Division given the assignment of capturing the strategically important village of Ste.Mère-Église. In a scene with the commanding officer, Brig. Gen. James Gavin (played by Robert Ryan), Gavin emphasizes to Vandervoort that the village “has to be taken and it has to be held. That’s why I gave you the job.”

Producer Daryl F. Zanuck paid my father a lot of money to appear in that scene. The Fox studio chief had recently antagonized my father with some ill-judged statements in an interview, and Dad was not inclined to accept the part. But Zanuck swallowed his pride and offered Dad a small fortune because he knew that he needed an actor whom the audience would identify as a go-to personality in a critical situation. He needed John Wayne. My father believed that in 1940 people needed—and got—an authentic go-to personality. They needed Winston Churchill.

Aissa Wayne is a daughter of John Wayne and a family practice attorney in Los Angeles, California. She is the author of John Wayne: My Father (1991) and wishes to thank Ron Cohen, Heidi Egginton, Scott Eyman, and John Farkis for help in researching this story.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.