Finest Hour 168

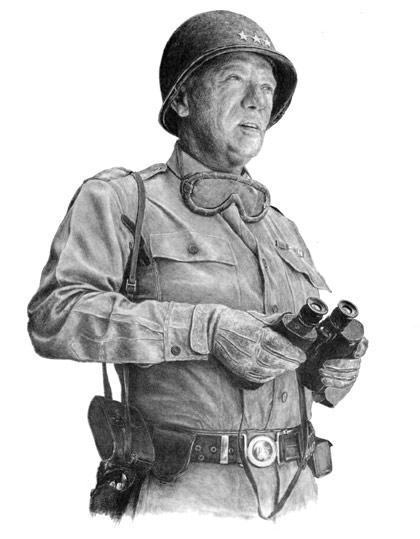

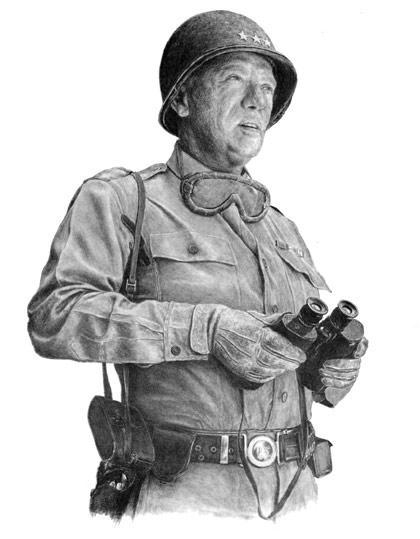

The British Lion and Old Blood and Guts: Twelve Common Threads

September 6, 2015

Finest Hour 168, Spring 2015

Page 21

By Paul J. Taylor

Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill and George Smith Patton, Jr., both overcame immense personal barriers to reach greatness, which they foresaw for themselves as children. Identical words described them: arrogant, charismatic, melodramatic, aristocratic, reckless, willful, audacious, defiant, hard-driving, mercurial, irrepressible, idiosyncratic, indispensable.

Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill and George Smith Patton, Jr., both overcame immense personal barriers to reach greatness, which they foresaw for themselves as children. Identical words described them: arrogant, charismatic, melodramatic, aristocratic, reckless, willful, audacious, defiant, hard-driving, mercurial, irrepressible, idiosyncratic, indispensable.

The common threads of their backgrounds, their perseverance, their bravery, and—ultimately—their history-making contributions form a fabric that should not be dismissed as mere coincidence. A dozen similarities form a fabric worthy of study.

2024 International Churchill Conference

1. Shared DNA

They were distant cousins, sharing four aristocratic family lines that made them either eighteenth or twentieth cousins once removed.1

A military genius began the Churchill legend. John Churchill’s 1704 victory over the French won acclaim, a title (Duke of Marlborough), and Blenheim Palace, where Winston was born in 1874. Winston’s mother, Jennie Jerome was American.

Patton knew that his family included prosperous colonial merchants, a Revolutionary War general, members of Congress, and Confederate Civil War leaders. Likely, he did not know that even earlier ancestors included monarchs and Magna Carta signatories. Wealth came from Patton’s California ancestors. His birthplace was an estate near modern San Gabriel.

2. Miscast dunces landed in the cavalry

Churchill’s parents were distant, while Patton’s pampered him to excess. Yet both boys were thought somewhat backward or even stupid.

Lord Randolph berated his son, while Jennie was rarely present. But Winston idolized his father and said his mother “always seemed to me a fairy princess: a radiant being possessed of limitless riches and power.”2

At boarding school at age seven, Winston responded with precocious disobedience. The headmaster whipped him, his parents refused to visit, and poor grades reflected his misery. When his beloved nanny found him covered with welts, he was moved to a smaller school run by two kind sisters. At age thirteen, he went to Harrow. Studying only what interested him, history and English, he was rated bright but hopeless.

Lord Randolph decided Winston was military material after seeing him play with toy soldiers. The boy was excited, but his father felt only that he was unfit for anything else. He joined a Harrow preparatory class for the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, but needed tutoring to pass the entrance exam on his third try.

Patton’s parents and a doting aunt quickly spotted his learning problems. Their protectiveness prevented formal education. Most likely dyslexic, an adult Patton wrote, “Any idiot can spell a word the same way time after time. But it calls for imagination…to spell it several different ways as I do.”3

Patton’s parents read to him for hours daily. He became an illiterate prodigy who memorized much of the Iliad and the Bible. Only at age twelve did Patton finally learn to read at a school for the privileged.

Patton aspired to West Point. The odds were steep. A tough exam and a competitive Congressional nomination would be daunting. His father learned the exam could be waived with an acceptable college record. Patton’s family legacy helped get him into the Virginia Military Institute, where he did well. A nomination was secured, and he was admitted to West Point in 1904.

3. Steeped in swashbuckling legacies

Enthralled by family exploits from early ages, both felt their fame would be even greater.

Patton’s grandson Robert recalls his father (also a general) and aunt explaining, “Because of the fame their father gained…[and] his sheer vividness in person, he reigns as the family’s exemplary figure, a goal he sought from childhood. He wrote, ‘It is my sincere hope that any of my blood who read these lines will be similarly inspired and ever true to the heroic traditions of this race.’”4

For Churchill, a life of fame was routine, especially with a father whose high office often put young Winston in the presence of great figures. His mother’s beauty and elite friends added more influence.

4. One-sided devotion

Churchill and Patton were both spellbound by their paternal ancestors. Their insufficiently romantic maternal forebears barely merited interest.

Churchill acknowledged his American side—especially when currying US support—but knew little about those roots. His maternal grandfather, Leonard Jerome, the so-called “buccaneer of Wall Street,” had a dubious reputation best left buried.

But Churchill had three ancestors who sailed on the Mayflower as well as family that included US presidents and at least four Revolutionary War soldiers who fought the British. One was at Valley Forge. “What is undisputed,” wrote his grandson, “is that this injection of American blood…kick-started to new triumphs the Marlborough dynasty.”5

Patton’s grandson calls the paternal fixation an omission; others say he rejected his mother’s side. Her father, Benjamin Davis Wilson, was a land baron and mayor of Los Angeles. Patton resembled Wilson physically and in self-reliance but regarded his grandfather’s life amassing wealth as vulgar. Yet, those riches made Patton one of the wealthiest officers in the army. He lived conspicuously with many servants, polo ponies, and custom-made uniforms.

5. Compensating for what nature did not provide

Neither came by his public personae naturally, and both worked tirelessly to overcome physical disadvantages to perfect their “on-stage” presence.

Churchill had a lisp. Practicing tongue-twisters helped, along with his tireless rehearsal of his speeches. Churchill’s friend F. E. Smith (Lord Birkenhead) said, “Winston has spent the best years of his life writing impromptu speeches.”6 Churchill’s grandson, also Winston, was told by his grandfather’s personal secretary “Jock” Colville, “your grandfather would invest [about] on hour of preparation for every minute of delivery.”7

Patton’s voice was squeaky. Those familiar only with actor George C. Scott=’s portrayal in the movie Patton would be surprised. Eisenhower aide Kay Summersby wrote that Patton had “the world’s most unfortunate voice, a high-pitched womanish speak.”8 His solution: endless rehearsals of fierce facial expressions and vulgarity that drew attention from his voice.

Robert Patton describes his grandfather’s work on a “visible personality.” “Creating it required a conscious performance that…he was able to refine, rehearse, and finally unleash.”9 Eisenhower agreed: “George Patton loved to shock people.…This may have seemed inadvertent but…he had, throughout his life, cultivated this habit. He loved to shake…a social gathering by exploding a few rounds of outrageous profanity. If he created any effect, he would indulge in more…[if not,] he would quiet down.”10

6. Mobilizing the English language

They also sharpened motivational skills that, when needed the most, reached new heights. Churchill inspired the free world; Patton stirred men to push beyond their limits.

Churchill’s grandson described the famous speeches: “his words were electric. Though the situation might appear hopeless…Churchill inspired the British nation to feats of courage and endurance, of which they had never known, or even imagined themselves capable.” War correspondent Edward R. Murrow famously said, “He mobilized the English language and sent it into battle.”11

Patton’s charisma lacked political correctness. The movie Patton opens with a less profane synthesis of preD-Day talks. Patton’s grandson observed, “A young officer…recalled him ‘literally hypnotizing us with his incomparable, if profane eloquence…you felt as if you had been given a super-charge from some divine source.’” Eisenhower wrote that Patton drew “thunderous applause.”12

Patton himself explained: “It may not sound nice to…little old ladies…but it helps my soldiers to remember. You can’t run an army without profanity, and it has to be eloquent profanity. An army without profanity couldn’t fight its way out of a piss-soaked paper bag.…I just, by God, get carried away with my own eloquence.”13

7. Old dogs, new tricks

Despite cavalry backgrounds, both were pioneers of the tank during the First World War. As First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill envisioned “Land Battleships.”14 France created its Renault tank in 1917, and made more tanks than all other nations combined. Renaults were America’s first tanks and Patton their commander.

8. Courage or recklessness?

They sought harm’s way while certain that a higher calling protected them.

Churchill faced danger as a combat soldier, an escaped prisoner, an early airplane pilot, and on rooftops watching the Blitz. He wrote his mother from the Northwest Frontier, “my follies have not been altogether unnoticed….Bullets…are not worth considering. Besides, I am so conceited I do not believe the Gods would create so potent a being as myself for so prosaic an ending.”15

Patton’s life was filled with falls, concussions, sickness, and car crashes. He called one “my usual annual accident.” His grandson called him relentlessly combative, and wrote, “Twice—once while a cadet and once while a cavalry lieutenant…he impulsively stepped from behind cover to stand erect by the targets during rifle practice to see how he’d react to bullets whistling by his ear.” In World War I, he led America’s first armor into battle atop a tank, was wounded, promoted, and decorated for bravery. Made a general in 1940, he wrote, “All that is needed now is a nice juicy war.”16

9. A cow as a gifted fox hunter?

“I have no more gift for politics than a cow has for fox hunting,” Patton wrote.17 But rejecting partisan politics was a standard line for army officers. Patton was as skillful as any politician at self-promotion. He pushed his reluctant father to run for the US Senate and, defeated, to seek appointments if they had useful prestige. An early posting for Patton was Fort Myer, overlooking Washington, D.C. Home to army brass, its officers had access to glamorous social events and the elite of the nation’s capital. On Fort Myer’s riding trails, Patton’s path just happened to cross often with Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson.

Churchill had prestige but only the appearance of riches. He decided his route to fame would be as a combat hero. His breakthrough came as a Boer War news correspondent. He was captured and made a daring escape across South Africa to safety. The electrifying news went worldwide, winning him a heroic reputation and a political career.

10. Foot-in-mouth disease

Despite masterful communication skills, public missteps upended their careers.

In a 1945 election broadcast, Churchill accused the Labour party of plans to create a Socialist state, saying: “no Socialist system can be established without a political police. They would have to fall back on some kind of Gestapo….” His daughter Mary wrote that, when her mother saw the script in advance, she begged him to remove the passage.18 He did not. The resulting fallout helped remove him from office.

Patton became frustrated as Bavaria’s post-war governor. He dutifully pursued “de-Nazifaction” by removing 60,000 former Nazis from jobs, but complained about the dismemberment of Germany. Newspapers reported that he compared Nazi party members to Republicans and Democrats. Patton refused a retraction; Eisenhower fired him on 4 September 1945. On 8 December he was critically injured in a car crash and died thirteen days later.

11. Crystal balls in focus

Both vividly saw Communism as just more totalitarianism. Churchill again became a messenger; Patton tried but did not live past his warnings.

After Ike expressed frustration to Churchill when Patton made a pre-D-Day speech seen as anti-Soviet, Churchill opined that Patton was only stating the obvious.19

Electoral defeat did not diminish Churchill’s world influence. President Harry S. Truman asked him to speak in Fulton, Missouri. His historic speech popularized the term Cold War. Nevertheless, when Churchill returned as Prime Minister, he tried to ease the arms race and reset the “special relationship” with the US. He failed. British influence had waned, both sides resisted, and Churchill’s health declined.

12. Above all, indispensable

One similarity dominates. Churchill and Patton were indispensable in the greatest war in history. They were not alone in that category (Eisenhower, belongs there for example), but their common ground is our focus.

Charles Krauthammer, Pulitzer Prize-winning author, wrote in 1999, “Person of the Century? Time magazine offered Albert Einstein…. Unfortunately, it is wrong. The only possible answer is Winston Churchill…because only Churchill carries that absolutely required criterion: indispensability….Without Churchill the world today would be unrecognizable— dark, impoverished, tortured.…Victory required one man without whom the fight would have been lost at the beginning. It required Winston Churchill.”20

Patton was no Churchill but, just as America was indispensable to victory, so was Patton to its army. Like General William Tecumseh Sherman in the American Civil War, Patton was not the top commander, but he had the best-trained and motivated armies, ruthlessly won the most critical victories, and ran over more enemy-controlled territory than any commander.

Eisenhower wrote, “The prodigious marches, the incessant attacks, the refusal to be halted by appalling difficulties in communication and terrain, are really something to enthuse about.” Ike loved Patton’s fortitude, “He never once chose a line on which he said ‘we will here rest and recuperate and bring up more strength.’”21

Historians argue whether the enemy respected Patton more than other Allied commanders. But the Germans were convinced that he would lead the invasion of Europe. Hitler reputedly described Patton as “the most dangerous man [the Allies] have,” and German Field Marshal Gerd von Runstedt said, “Patton was your best.”22

Paul J. Taylor is a retired healthcare executive and longtime member of The Churchill Centre living in Hingham, Massachusetts. He is a distant cousin of both Churchill and Patton.

Endnotes

1. The Churchill and Patton families are related through any of four ancient common ancestors: Isabella Beauchamp, Sir Robert de Clare, Richard FitzAlan, or Sir Edmund Mortimer.

2. William Manchester, The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill, Visions of Glory, 1874–1932 (New York: Little Brown, 1983), p. 118.

3. Carlo D’Este, “Gen. George S. Patton, Jr. at West Point, 1904–1909,” Armchair General, 14 Nov. 2006.

4. Robert S. Patton, The Pattons: A Personal History of an American Family (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, 2004), p. ix.

5. Winston S. Churchill, “Churchill’s American Heritage,” www.winstonchurchill.org.

6. Clayton Fritchley, “A Politician Must Watch His Wit,” The New York Times Magazine, (3 July 1960).

7. Winston S. Churchill, Never Give In (Scranton, PA: Hyperion, 2003), p. xxv.

8. Kay Summersby Morgan, Past Forgetting: My Love Affair with Dwight D. Eisenhower (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), p. 162.

9. Patton, p. 196.

10. Dwight D. Eisenhower, At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1967), p. 269.

11. Churchill, Never Give In, p. xxi.

12. Patton, p. 265.

13. Charles Provence, The Unknown Patton (CreateSpace Independent Publishing, 2009).

14. Winston S. Churchill speech, 4 March 1904, at Royal Aero Club Dinner, Savoy Hotel, London.

15. Carlo D’Este, Warlord: A Life of Winston Churchill at War, 1874–1945 (New York: Harper Collins, 1995), p. 70.

16. Patton, p. 248.

17. Ibid., p. 259.

18. Mary Soames, Clementine Churchill, The Biography of a Marriage (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1979), pp. 503–04.

19. James C. Humes, Eisenhower and Churchill: The Partnership That Saved The World (New York: Crown, 2010).

20. Charles Krauthammer, Things That Matter: Three Decades of Passions, Pastimes and Politics (New York: Crown Publishing, 2013), p. 22.

21. Alan Axelrod, Eisenhower on Leadership (San Francisco: Josey Bass, 2006), p. 126.

22. Carlo D’Este, Patton: A Genius for War (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1995), p. 701.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.