Bulletin #200 — Jan 2025

No Ordinary Life

January 1, 2025

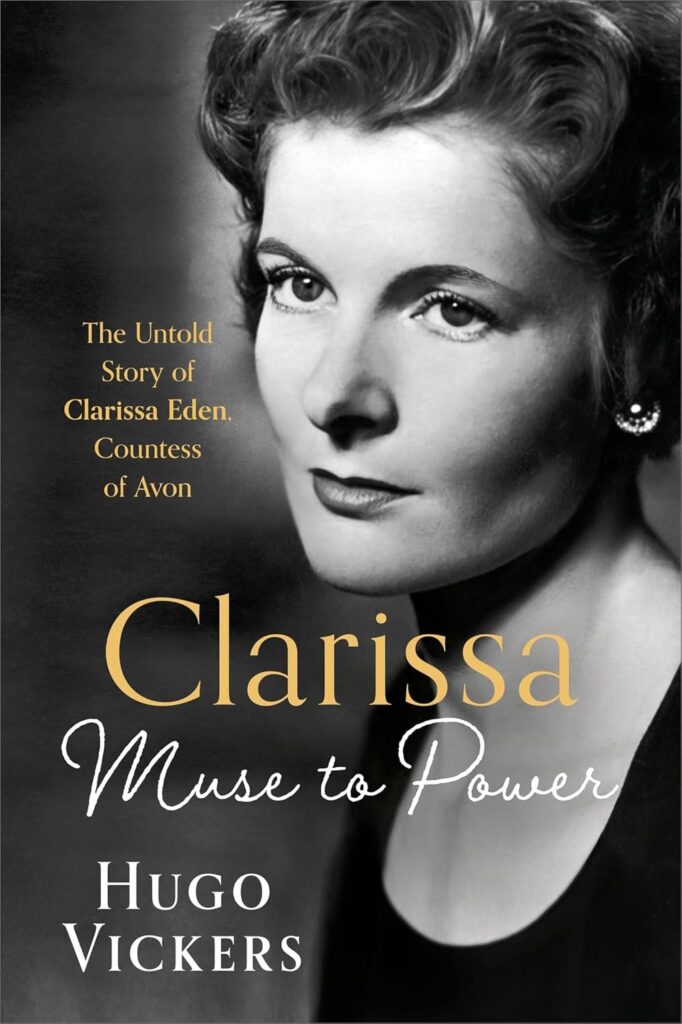

Hugo Vickers, Clarissa: Muse to Power, The Untold Story of Clarissa Eden, Countess of Avon, Hodder & Stoughton, 2024, 352 pages, £30. ISBN 978-1399736770

Review by CELIA LEE

Best known for having been the niece of Winston Churchill and the wife of Anthony Eden, Anne Clarissa Nicolette Spencer-Churchill, known as Clarissa, had little to say by way of enthusiasm about her childhood or schooling.

Veteran biographer Hugo Vickers knew Clarissa rather better than most, having been friends with her for forty years, and he has produced a fine biography of an intellectual figure from a bygone age. That said, having also known Clarissa as well as her brother Peregrine and written a biography of their father John (known in the family as Jack) and uncle Winston, Vickers makes some claims about Clarissa’s antecedents with which I disagree.

Like many before him, Vickers questions the paternity of Clarissa’s father, John Strange Spencer-Churchill (Jack), and agrees with those who credit not Lord Randolph with being Jack’s father but, amongst others, John Strange Jocelyn, 5th Earl of Roden. Jack was born in Dublin on 4 February 1880. Yet the present earl confirmed to me by letter that it was not until 10 January 1880 that Jocelyn arrived for the first time to claim his estate Tollymore in County Down and signed the house book by way of evidence. Jocelyn was a friend of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, then residing in Dublin as the Viceroy of Ireland. The duke’s younger son, Lord Randolph Churchill, serving as his father’s secretary, lived with his wife Jennie and their young son Winston at the Little Lodge in Phoenix Park. In the process of returning to his home in England, Jocelyn paid the duke a visit. Whilst there, the infant Jack was born prematurely, and Jocelyn stood sponsor at the baptism. That is all there was to that.

Vickers then makes much of never-before-published letters bequeathed to him by Clarissa revealing that Winston had a romantic interest in Clarissa’s mother Lady Gwendeline Bertie (known as “Goonie”) before her engagement to his brother. That may have been, but Goonie had been meeting with Jack in secret on horseback in Wytham Woods for many months before the couple announced their engagement. Clarissa told me that her maternal grandparents would “never have accepted Winston as their son-in-law” and that “Jack was considered the brains of the family.” The Berties viewed Winston “as a wild Maverick sort of character.”

Vickers also makes the dubious claim that Clarissa’s biological father was the MP Harold “Bluey” Baker, who was one of Goonie’s wide circle of Liberal Party friends. There is, though, no obvious reason for doubting Jack Churchill to have been the father of Clarissa. After serving in the First World War, he returned home from the Western Front at the end of March 1919. Clarissa was conceived around six months later and born 28 June 1920. As for Baker, he never married. Certainly, he was a friend to Clarissa and made her the beneficiary of his estate. When he died in 1960 his will provided Clarissa with £3,000, his books, and some land, but no claim that he was her biological father. Given that her mother was a deeply devout Catholic, infidelity seems unlikely.

Fuelling the arguments over her parentage are spiteful remarks Clarissa made in her youth about her father’s intellect. In fact, Jack, fluent in French, was constantly top of his form at Harrow, and the school’s headmaster proposed him for Oxford. Jack’s mother, however, had squandered the inheritance of her sons that would have made this possible. Winston joined the army, and Jack was forced into the City of London to train as a stockbroker.

As for Clarissa, her life really took off after a fashion in 1937 when she arrived in Paris. Attending lectures at the Sorbonne, she also learnt to speak French and took painting lessons. Returning home enthused by the experience, Clarissa was set on a life of intellectual pursuits, including art classes at the Slade School. In 1939, she went to live in Oxford to further her education but returned to London when war was declared in September to work at decoding messages in a dismal basement at the Foreign Office.

Absent from this biography is Clarissa’s involvement with two Russian agents during the war. Harry Smollett (Hans Peter Smolka) was head of the Russian section at the Ministry of Information and responsible for organising pro-Soviet propaganda. Clarissa worked for Smollett as a research assistant on the propaganda newspaper Britanskiy Soyuznik, unaware that Smollett had been recruited as a Soviet Agent by Kim Philby. A third Soviet Agent, Guy Burgess, had become increasingly exercised by the need for a Second Front against Germany and lobbied various people, including Clarissa, because her uncle was then Prime Minister. The relationship between Clarissa and Burgess went even deeper, however. Her brother Peregrine confirmed to me that she was briefly engaged to marry Burgess. After the engagement was broken off, she kept the ring and continued to wear it as a dress ring as late as the year 2000.

Following the war, Clarissa worked for various magazines. Her articles published in Spotlight display the breadth of her knowledge and education. She wrote reviews of Rodney Ackland’s stage adaptation of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment; Eisenstein’s film Ivan the Terrible; Bertrand Russell’s History of Western Philosophy; the new opera season at Sadler’s Wells; Laurence Olivier’s King Lear; and commentary on John Gielgud’s performance as Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment.

Clarissa’s love life involved a series of affairs, the longest being with a married man, Raimund von Hofmannsthal. Following nine years of secret rendezvous with him and no prospect of marriage, her luck changed. She received a proposal from Anthony Eden, soon to succeed her uncle as Prime Minister. The attraction was clearly one of politics and power. Eden told her that he was not really a Conservative but an old-fashioned Liberal. Clarissa and her mother had remained Liberal supporters after Winston left the party and rejoined the Conservatives in the mid 1920s. Married from 10 Downing Street at the Caxton Hall in August 1952, Clarissa was besieged by press and admirers. It may have been a registry-office wedding because Eden was divorced, but it was very much a love match.

Eden finally became Prime Minister three years later in 1955 at age fifty-eight and following a series of health problems. Together, the Edens travelled a good deal. Clarissa saw something of the world but at home had to endure the resentment from some MPs and others, who believed she controlled her husband’s political decisions.

Anthony Eden’s political career famously collapsed during the Suez Canal crisis in 1956. There was Russian involvement, and the nation held its breath as the press warned of the risk of a third world war. In a famous address given at the Eden House care home, Gateshead, Clarissa affirmed that “Russian tanks, Russian planes, Russian armoured vehicles, Russian ammunition and Russian rockets are reported to have been found in vast quantities.…”

The crisis took its toll on Anthony Eden’s fragile health and marked the beginning of the end of his premiership. Throughout, Clarissa steadfastly supported her husband and continued to do so for the rest of his life. After Eden’s death in 1977, she returned to her bohemian lifestyle and a long widowhood, dying in 2021 at the grand old age of 101.

Celia Lee is co-author of Winston and Jack: The Churchill Brothers (2007) and The Churchills: A Family Portrait (2021).

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.