Bulletin #176 — Jan 2023

Stalingrad

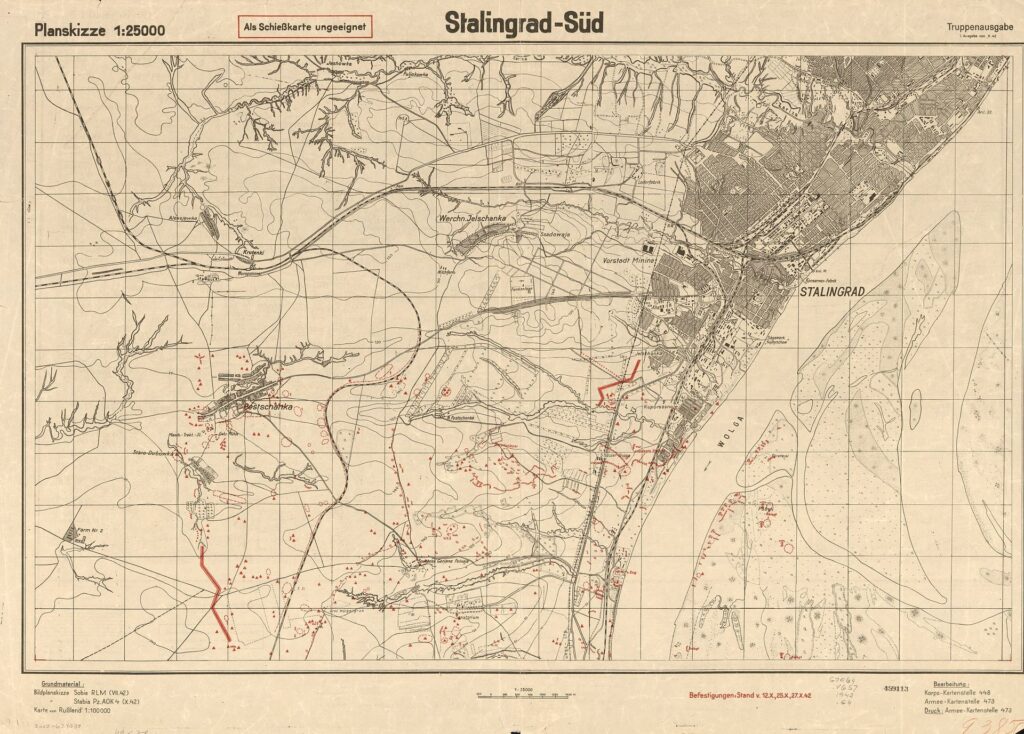

German map of Stalingrad, 1942

December 30, 2022

80th Anniversary of Pivotal Battle

By ROBERT A. MCLAIN

Much has already been said about Winston Churchill’s views on Russia, as well as his relationship with Joseph Stalin. As Andrew Roberts pointed out recently in these same pages, Sir Winston held a consistent position on the Russian people and the country’s leadership throughout his career (see FH 194). He saw the population as hardy and long-suffering and its government oppressive, whether Tsarist or Bolshevist. Still, the fact that diametrically opposed figures such as Churchill and Stalin cooperated to defeat Nazi Germany remains worthy of revisiting in two ways. First, it is important to consider Churchill’s views of Germany and Russia together, over a long trajectory. Secondly, and more narrowly, to what degree did Churchill’s strategic vision help to turn the tide in the crucial months of early 1943, when Germany was defeated simultaneously in North Africa and at Stalingrad? Stalin constantly belittled British efforts as paltry, but did their impact exceed their numbers, given Russia’s desperation in the East?

Sweeping Vision

Readers are familiar with Churchill’s sweeping vision of history and his sense from an early age that he was destined one day to help save Britain. His birth in 1874 placed him imperfectly astride the latter part of the “long” nineteenth century, that period beginning with the French Revolution and ending with the start of the First World War. Churchill the historian was no mere observer of events, but a direct participant who grew up in an age of intense imperial competition. This was due not only to Anglo-Russian competition in Central Asia, the “Great Game,” but also to Germany’s emergence as an ambitious, dynamic military power from a chrysalis of disjointed states.

The mid-1870s also marked the height of conservative Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli’s power and his successful efforts to have Queen Victoria crowned “Empress of India”; his final months in office also marked the Second Anglo-Afghan War and the effort to create a buffer state between India and the Tsar’s encroachments. As Roberts further points out, Churchill immersed himself in the study of Disraeli’s domestic and imperial policies while serving in India in the 1890s. Churchill’s copies of the Annual Register, housed in the Churchill Archives at Cambridge University, contain extensive marginalia on the Disraeli years. Disraeli’s progressive Toryism and open antagonism to Russian expansion played a vital role in shaping young Winston’s worldview.

2024 International Churchill Conference

As dangerous as Russia appeared to the defenders of Britain’s empire, simple geography dictated that the competition had a different hue than that with Germany. The Great Game played itself out on the peripheries, where agents of the Great Powers lurked in indigenous garb, waging war, negotiating with local potentates, and seeking to extend the influence of their respective realms. To this day the city of Abbottabad in northern Pakistan attests to that competition. Major James Abbott lent his name to it in the 1850s and helped to found it after engaging in years of intrigue along India’s northern frontier. Churchill would have passed through the same environs as a member of the Malakand Field Force in 1897. Churchill ardently defended the empire, but the clash of Russian and British interests in South and Central Asia, though dire, did not threaten the United Kingdom directly in the same way as Germany did.

The Second Reich, imperial Germany, represented a different type of danger. It lay at the heartland of Europe. Its unification and militarization in the late nineteenth century threatened to upset traditional balances of power, particularly in the 1890s when Queen Victoria’s grandson, Kaiser Wilhelm II, began constructing a first-class naval fleet. Even casual observers wondered why Germany, with most of its coastline lying in the choked off Baltic Sea, would build dreadnoughts unless it were for equally dreadful purposes. It did not help that the Kaiser had a gift for combining bad foreign policy decisions with appallingly bad public statements that were diplomatic crises in themselves. He openly congratulated the Boers during their conflict with Britain and more than once referred to the British cabinet as “unmitigated noodles.” Such gaffes, alongside the construction of a new battle fleet, made Anglo-German naval rivalry a dominant feature of British foreign policy in the 1890s.

Churchill’s extensive travels in the 1890s informed his view of both rivalries. Moving about and fighting in campaigns in India, Sudan, and South Africa just as the Boer War began left him convinced in the rightness of the Empire, despite its flaws. In India, he saw the Raj as a stabilizing power. In South Africa, he believed Britain provided better governance than the Afrikaners, whom he considered to be racist even by the standards of the time. Closer to home, the naval arms race with Germany threatened the “civilizing mission of Empire,” since the Kaiser’s fleets might directly challenge the Royal Navy. He was immersed in the debates that contrasted Germany’s rise with a fear of British decline. In this environment, there was a strong cultural current that saw “Prussianism,” a combination of militarism and soulless industrial rationalization, as a potent threat.

If Germany took over continental Europe it could leave Britain isolated and weak. If that were to happen, only Canada and the United States, far across the Atlantic, could possibly offer relief. The irony is that this happened in 1940 rather than 1914. Churchill’s allusion in his “Finest Hour” speech, that stopping Hitler would prevent “a new Dark Age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science,” had a history. The Nazis were simply the latest version of German authoritarianism backed by a modern, efficient war machine.

The Realist

Churchill believed for most of his life that both Russia and Germany represented dangers to what he regarded as a more just and fair Anglocentric world, but he also believed that Hitler represented the worst of the worst. More than any European stateman, Churchill saw the Führer immediately for what he was, a looming evil. In 1934, Churchill appeared as one of eleven guests in a popular series on war and its causes. He bluntly argued that Germany’s new generation was “taught from childhood to think of war and conquest as a glorious exercise” and therefore represented the greatest danger to future peace. It was incredibly perceptive. Churchill recognized the pathological violence of the Nazi system as not simply a means to power, but rather as a reason for their being. Even so, when the sponsors published the talks as a collection entitled The Causes of War, they removed Churchill’s portion as inflammatory and “unsuitable for issue in a book.”

We should recognize that Churchill’s soaring rhetoric sometimes clouds a simple fact: he was at heart a foreign policy “realist,” cognizant of diplomatic, political, and military limitations constraining Britain and its empire. He harbored no illusions about Stalin. During his first meeting with the Soviet dictator in August 1942, Churchill directly asked him what was more stressful, the current war or the policy of forced collectivization that had resulted in the deaths of millions Soviet peasants. Stalin explained away his policy as “very bad and difficult,” but necessary “if Russia were to avoid devastating periodic famines.” As for the massive deaths, Stalin insisted that the more prosperous peasants, the Kulaks, suffered especially harsh reprisals, but only because “the great bulk were very unpopular and were wiped out by the laborers.” Churchill later recalled that he could not overlook the “strong impression” of “millions of men and women being blotted out or displaced forever.” Even so, “with a World War going on all around us it seemed vain to moralize aloud.”

When Churchill’s “visit to the Ogre in his den” turned directly to military matters, the mood grew bitterly antagonistic. In part, the trip had been made to notify Stalin that there would be no Second Front, a cross-channel invasion of France, in the immediate future. It was, he said, “like carrying a large lump of ice to the North Pole.” John Dunlop, the translator assigned for the trip, remarked that “Stalin’s face crumpled up into a frown” when he received the news. At one point he accused the British of cowardice in being afraid to fight the Germans. The fact that Britain stood alone in 1940 while the Soviet Union was at best neutral eluded Stalin. Churchill objected strongly, and his report on the extent of Britain’s bombing campaign decreased the tension. Stalin, though still unhappy, brightened considerably when the Prime Minister revealed the secret plan for an upcoming Anglo-American landing in North Africa, Operation TORCH. It was a “turning point in our conversation,” according to Churchill. The ruthless and highly intelligent Stalin immediately saw the advantages of the operation.

Opportunity Loss

Here, we come to an important juncture that goes beyond the academic debates over the amount of weapons and matériel that Britain shipped to the Soviet Union early in the war. Postwar assessments of British aid tend to suggest that it made little difference to the early Soviet war effort, that it was only later when the weapons forged in the Midlands and the American Midwest began to make their way to the Eastern Front in great quantities that Western aid helped to turn the tide. This is neither a fair nor an accurate point of view. The inflow of weapons to degrade the German army alone does not tell the whole story, nor does it shed full light on how Churchill’s vision helped siphon off Axis forces. Indeed, it is not merely the degree to which British aid allowed Stalin’s regime to survive and persevere in the winter of 1942, but also how the Prime Minister’s strategic judgment created “opportunity loss” for the German army.

The line between defeat and eventual victory remained razor thin until the winter of 1942, when the Axis forces began to ebb in Russia, North Africa, and the Pacific. The most crucial point in the “Hinge of Fate” came at Stalingrad between November 1942 and February 1943, when Soviet forces entrapped and destroyed the entire German Sixth Army, in addition to Romanian, Italian, and Hungarian satellite armies. The Soviet victory came at a tremendous cost, but it inflicted a devastating defeat on the Wehrmacht. At its most perilous moments, a battle that consumed more than one million lives hinged on handfuls of Soviet soldiers stopping a last, desperate Nazi attempt to capture a strip of land along the Volga River measured in yards. In this instance, a very few additional troops would have enabled the German commander, Friedrich von Paulus, to secure his objectives and possibly doom the Soviet war effort.

Fortunately for the Allies, those Wehrmacht forces were in North Africa, with many behind British barbed wire. Some historians portray the North Africa campaign as a mere “sideshow” compared with the Eastern Front, with its staggering death tolls in 1941–42. It is easy to see why. Stalingrad encompassed the destruction of at least 500,000 Axis troops through combat or subsequent starvation in captivity. Soviet archival records indicate approximately 480,000 Red Army dead, although that number is certainly too low. There is in fact an endless supply of remains still in the battlefield. Archaeologists and casualty recovery groups work every summer to locate and properly bury thousands of unidentified soldiers. Moreover, the Soviets were not above manipulating such figures if they thought the truth might reflect the incompetence and sheer bloody-mindedness of their leadership, particularly Stalin (see the 2022 Russo-Ukraine War).

Still, the shocking numbers have the unintended effect of overshadowing the interconnected nature of the fighting in the crucial fall of 1942 and how far-flung campaigns provided the narrowest of margins of victory for the Red Army. To Churchill’s credit, he realized that the North African campaign could still erode German resources in a decisive way. Large numbers of German troops, and phenomenally large numbers of Italian troops, were captured there during the fighting in 1941 and ’42. This was crucial to keeping Russia in the war.

The Second Battle of El Alamein, for example, overlapped with some of the most desperate fighting in Stalingrad and ended just days before the encirclement of the German Sixth Army. In one of the great blunders of the war, Herman Göring, the head of the Luftwaffe, assured Hitler that he could fly in five hundred tons of supplies per day to the army trapped inside the “Kessel,” or cauldron. This was an unrealistic assessment, since four hundred German aircraft were already withdrawn from the Eastern Front to support the North Africa campaign, where supplies were also short due to the success of Allied naval operations. When one considers that the Luftwaffe lost five hundred transport planes to enemy action during the Stalingrad battle, Göring’s claim becomes even more startling. Instead, German soldiers froze and starved to death in the tens of thousands. More than 200,000 died in the cauldron. Of the 95,000 who were captured at the end of the battle, only five thousand ever returned to Germany, some ten years after the war ended.

Extensions

Even smaller actions, although disastrous for the Allies, often locked German units in place by reinforcing Hitler’s anxiety about the opening of a Second Front. For example, the Dieppe Raid of August 1942, launched as a “test” of a cross-channel invasion, resulted in heavy casualties and the capture of most of the Canadian troops involved. Churchill argued that it increased German anxiety about the coast of Occupied France and led German commanders to keep “troops and resources in the West” and “take [some of] the weight off of Russia.” Churchill, along with a number of apologists, also considered it a “costly but not unfruitful reconnaissance in force,” since it was tactically a “mine of experience” on how to conduct amphibious operations and the need for heavy naval gunfire support and better techniques.

Although Hitler warned his Western commanders not to read too much into the failed raid, he did note, “we must realize that we are not alone in learning a lesson from Dieppe. The British have also learned. We must reckon with a different mode of attack and at quite a different place.” While the Eastern Front remained Hitler’s primary concern, the Dieppe Raid added to his unease and further undermined his already tense relationship with his generals.

Just eleven days after the battle of El Alamein ended, Stalin telegraphed Churchill as the Red Army closed the ring around German forces in his namesake city on the Volga. In the words of the Soviet dictator, “the operations are developing not badly.” It was one of the great understatements of the war. The Soviets held Stalingrad by the slimmest of margins, in no small part because of the manpower and logistical costs of the North African campaign. Churchill had parried Stalin’s resentment in August 1942 and proven that the fighting carried out by the Allies in North Africa amounted to an extension of the Eastern Front.

Robert A. McLain is Professor of History at California State University, Fullerton. The full-length version of this article, including endnotes, appears in issue #200 of Finest Hour. For more about Churchill and Russia, see Finest Hour #201, which is forthcoming.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.