Bulletin #171 — Aug 2022

Fake Churchill

July 30, 2022

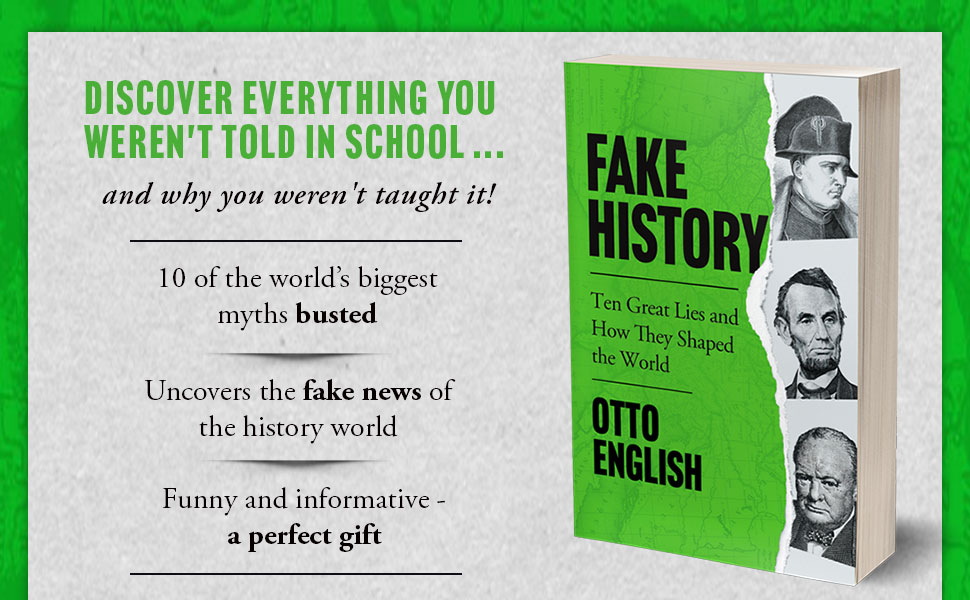

Otto English, Fake History: Ten Great Lies and How They Shaped the World, Welbeck, 2022, 352 pages, $14. ISBN 978–1787396425

By ALASTAIR STEWART

There is a fascinating phenomenon called the Mandela effect: Multiple people can sometimes share false memories. This phenomenon was recorded by paranormal researcher Fiona Broome, who documented having detailed memories of news coverage of Nelson Mandela dying in prison in the 1980s. This was obviously not so, but a legion of people was convinced they knew the same thing.

Many swear that Darth Vader said, “Luke, I am your Father” or remember Margaret Thatcher saying, “there is no such thing as society,” but neither was said as people often remember them. And Otto English has had enough. His new book Fake History: Ten Great Lies and How They Shaped the World is a wonderful elucidation of the fake history that stalks us today, particularly on social media.

English, the pen name of writer and journalist Andrew Scott, has made it a mission, as F. Scott Fitzgerald commanded, to “beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” Over ten chapters, Scott challenges modern myths and figures who are unfairly elevated or incorrectly remembered. And first up for the chop is Winston Churchill.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Scott attacks what he regards as politically motivated fables to overturn the taboo on criticising Churchill. Indeed, he contends the “thousands” of biographies written will be full of things “Churchill never said…or never did.” Scott loathes idolatry. He resents the Churchill cult and the shameless hagiography. His targets for this chapter are twofold: the proliferation of lies and the reasons for Churchill’s fossilisation in our culture.

A significant issue is a conflation of what the late Donald Rumsfield called “known knowns” and “known unknowns.” Few would deny the circumstances of Churchill’s ducal birth, but presupposing this generated a sense of entitlement that affected his leadership and decision-making is questionable.

Any true Churchill enthusiast delights in new takes on the man’s life and career. It is hard to accept that Churchill’s fame is due exclusively to his supporters “pushing his legacy boisterously to the front of history’s queue.” Most Churchill fans will look the truth in the face and weigh it up in the scale of a ninety-year life.

Robert Rhodes James, who published Churchill: A Study in Failure more than half a century ago, started a process of counterbalancing the heroics of Churchill’s reputation. Nigel Knight’s Churchill: The Greatest Briton Unmasked (2008) is at least a handy go-to for a Churchill body slam, alongside Churchill’s Secret War (2010) by Madhusree Mukerjee, and Geoffrey Wheatcroft’s Churchill’s Shadow: An Astonishing Life and a Dangerous Legacy (2021).

Scott’s anecdotal prose is both accessible and genuinely funny, and an entire book could be given over to addressing all the popular myths and maxims and quips falsely left at Churchill’s doorstep. In the section on “fake history works both ways,” he touches on some of the more brazen false charges that need dispelling.

Churchill did not send tanks into the so-called Battle of George Square in 1919. Not only did he have nothing to do with the incident, he also did not deploy troops during the 1910 Tonypandy Riots in Wales (Churchill “actually halted the deployment of cavalry and did not send the army in”).

Immediately in reading these pages, one’s mind is drawn to Tariq Ali’s latest effort, Winston Churchill: His Times, His Crimes. English has none of Ali’s tortured prose about a subject he clearly hates. If anything, Scott is the kind of storyteller dedicated to imparting a discerning toolkit, and Churchill, Hitler, Ghengis Khan, and Abraham Lincoln are his muses.

Scott’s book is the antidote to the deluge of the Twitter generation. It should be read and understood as the spotter’s guide to rubbish circulating on the internet. It does not claim to be an authoritative deconstruction of every concocted rumour turned factoid out there. It takes some of the more outrageous and ubiquitous myths that hang on in the digital sphere and breaks them down.

English is correct to highlight the millions of memes and GIFs which falsely attribute Churchill quotes such as “if you’re going through Hell, keep going.” But it cannot be ignored that there is a concerted effort among scholars to set the record straight, notably by Richard M. Langworth, the founder of the International Churchill Society now working on the Churchill Project at Hillsdale College.

The irony is that most Churchill enthusiasts would agree with this book’s purpose. Critiques and stimulating assessments are gold dust. Fake History is the enemy of truth. The politicisation of Churchill’s legacy into a modern populist tool cannot be excused, especially if people try to write that history as former prime minister Boris Johnson did in The Churchill Factor (2014).

Scott thankfully does not shy away from his rage about today’s politics. There are references to Donald Trump and Johnson as purveyors of the kind of tokenistic trash that necessitates the book’s existence. Churchill is neither a bogeyman in Scotland nor a sceptre-wielding vanguard for Little Englanders. The truth is grey, the lies pernicious, and balancing fact with fiction a constant struggle.

English’s style is more Patch Adams than revolutionary. Here is the funny and brilliant doctor to straighten you out. There’s a great deal of indigenous humour as he locks you into a room and forces you to go cold turkey from the pills of half-truths you have been guzzling. It is a delightful, light touch needed to realign the wayward truth.

Fake History is a pleasure, but one in which you greedily, grubbily wish for Scott to apply his wit and insight to every other lie out there, not least the ones pushed by so-called Churchill fans with an agenda. Pick up this book, indulge Scott’s fury, but appreciate his timely intervention in a world fast losing touch with the facts and history.

Alastair Stewart is a Scottish public affairs consultant and freelance writer, whose work often appears in The Scotsman and other newspapers.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.