Bulletin #171 — Aug 2022

Churchill and Collins

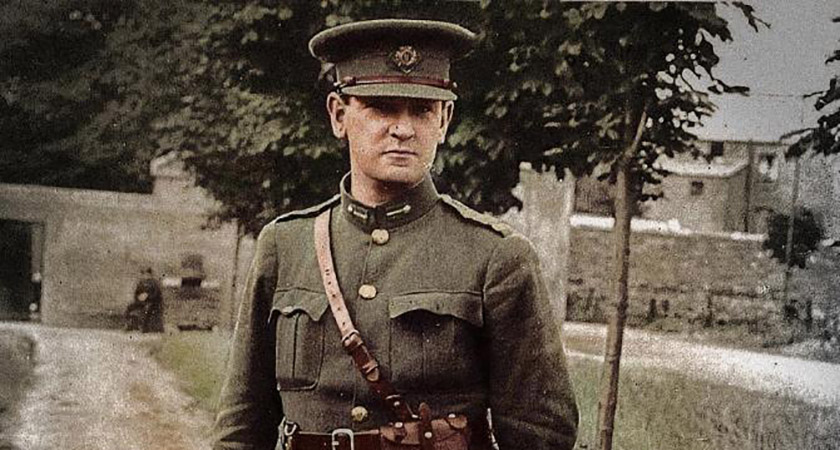

Michael Collins

July 30, 2022

Irish Leader Died 100 Years Ago

By MICHAEL MCMENAMIN

This month marks the one hundredth anniversary of the assassination of Michael Collins, the Irish Nationalist leader who helped to bring about the independence of Ireland from the United Kingdom. Collins and Winston Churchill became acquainted with each other when both were party to the negotiations that resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which established the framework for Irish self government. They formed a rapport that served them well in 1922, when Churchill was Colonial Secretary with responsibility for implementing the treaty.

In the summer of 1922—at Churchill’s urging—Collins abandoned his earlier attempts that year to reach an honorable accommodation with Eamon de Valera, who had sent him to London to negotiate a treaty and then denounced him when Collins did not bring back what de Valera knew from the outset was impossible. Collins now fought back and waged war against de Valera and those of his former comrades in the Irish Republican Army (IRA), who opposed the treaty and were attempting through violence and terrorism to overthrow the elected government of the new Irish Free State.

In his book The Aftermath, Churchill wrote about what he and Collins went through in 1922 to reach the point where Collins believed he had no choice but to wage war against the anti-Treaty forces by shelling the Four Courts building in Dublin, which was held by IRA rebels. In this way Collins could preserve the new Free State and the accomplishments of the Irish Republican Brotherhood in the Anglo-Irish War of 1919–1921.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Churchill’s portrait of Collins illustrates how well he managed to understand him and gain his trust: “Michael Collins had not enjoyed the same advantages in education as his elder colleague [Arthur Griffith]. But he had elemental qualities and mother wit which were in many ways remarkable. He stood far nearer to the terrible incidents of the conflict than his leader [de Valera]. His prestige and influence with the extreme parties in Ireland for that reason were far higher, his difficulties in his own heart and with his associates were far greater.”

As part of Collins’ attempts to reach a conciliation with de Valera and the IRA, the two had agreed on 20 May to a division of seats in the June elections to the new Irish Parliament: Free State supporters were to have 64 seats, treaty opponents were to have 57. Churchill opposed this, but rather than say so, he invited Collins and Griffith—who opposed the Collins-de Valera Agreement—to London for discussion. Collins and Griffith spent three days with Churchill and persuaded him that free elections would have been impossible because “Small bands of armed men could have seized and destroyed the ballot boxes and in other ways prevented the free exercise of constitutional rights.”

Collins promised he would stand by the treaty because he would have a majority in the new legislature, however small. As Martin Gilbert wrote, “Churchill, [Prime Minister David] Lloyd George and [Conservative Leader] Austen Chamberlain were impressed by these arguments. Certainly, Collins appeared to be seeking a conciliatory solution within the Treaty,” whereas the Northern Ireland Prime Minister, Sir James Craig, had recently “issued a direct challenge to the Treaty.”

On 30 May, Churchill persuaded the Cabinet to support the Collins-de Valera Agreement. On 31 May, Churchill’s speech in the House of Commons gave a complete account of the Irish situation including a defense of the Collins-de Valera Agreement and the good faith of Collins and the Free State Government. The next day, Austen Chamberlain wrote to the King describing Churchill’s speech: “It was a masterly performance—not merely a great personal and oratorical triumph, though it was both of these, but a great act of statesmanship.”

More importantly, Collins heard the speech. As Churchill later wrote: “Immediately after the debate, Michael Collins, who had listened to it, came to my room…interested in the debate. ‘I am glad to have seen it,’ he said, ‘and how it is all done over here. I do not quarrel with your speech’….Before he left he said, ‘I shall not last long; my life is forfeit, but I shall do my best. After I am gone it will be easier for others. You will find they will be able to do more than I can do.’…I never saw him again.”

On 28 June at 4 am, Free State Army troops—acting upon the orders of Collins and using artillery supplied to them by the British Army and approved by Churchill—opened fire on the Four Courts building occupied by the IRA. This marked the beginning of the Irish Civil War, a conflict that outlasted Collins.

On 22 August, Collins, in Churchill’s words, “moving audaciously about the country rallying and leading his supporters in every foray, was killed in an ambush” by IRA forces. Churchill wrote that, before his death, Collins “sent me a message through a friend for which I am grateful. ‘Tell Winston we could never have done anything without him.’”

Michael McMenamin is editor of the “Action This Day” column in Finest Hour. You can learn more about Churchill’s involvement with Irish independence and his partnership with Collins in the latest issue of Finest Hour, which is on the theme “Churchill and Ireland.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.