Bulletin #142 – Apr 2020

Churchill Style

March 30, 2020

By BARRY SINGER

The month after Winston Churchill became Prime Minister in 1940, a doctor was chosen to “keep an eye” on the war leader’s health. The physician was a general practitioner named Charles Wilson, who later became Lord Moran. Wilson first presented himself at Admiralty House, where Churchill was still living before moving into Downing Street.

“Though it was noon,” Wilson recorded, “I found him in bed reading a document.” “After what seemed like quite a long time,” Churchill, “put down his papers and said impatiently:

‘I don’t know why they are making such a fuss. There’s nothing wrong with me.’

At last he pushed his bed-rest away and, throwing back the bed-clothes, said abruptly:

‘I suffer from dyspepsia, and this is the treatment.’

“With that he proceeded to demonstrate to me some breathing exercises. His big white belly was moving up and down when there was a knock on the door, and the PM grabbed at the sheets as Mrs. Hill [his secretary] came into the room.”

Days later, one of Churchill’s Private Secretaries, John Martin, felt compelled to point out that six people had died of heart failure during a recent air raid warning. Standing before Martin wrapped in a huge towel, fresh out of his bath, Churchill replied that he was more likely to die of overeating, but not yet, “not when so many interesting things are happening.”

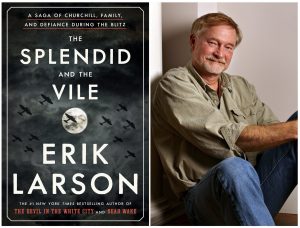

Barry Singer is the author of Churchill Style (Abrams Image, 2012) and the proprietor of Chartwell Booksellers in New York City.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.