Bulletin #53 - Nov 2012

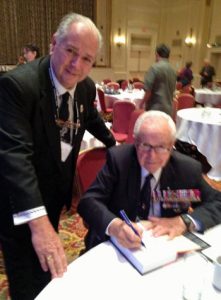

29th Int’l Churchill Conference: The Veteran’s Panel – We Were There

November 2, 2012

A recap of an outstanding panel which took place at the most recent Churchill Conference in Toronto.  Rt. Hon John Turner, Jack Rhind, George MacDonell, General Richard Rohmer

Rt. Hon John Turner, Jack Rhind, George MacDonell, General Richard Rohmer

By Gordon W. Walker, Q.C.

A great highlight of the Churchill Centre 2012 Conference in Toronto in October was what was labeled “The Veteran’s Panel – We were there”. Indeed they were!

Canada played a huge role in WW II, punching far above its weight. A country of barely 11 million people in 1939, Canada fielded over 1 million men in uniform by War’s end. The Army saw action first in Hong Kong. But two years prior to that the Canadian Army was on guard in Southern England, and for a while it stood as the only defence to London from the anticipated German invasion. The Army saw action in Italy in 1943 and 44 and it was the British, Americans and Canadians that landed on Normandy Beaches in 1944 and carried through France to Germany for victory less than a year later. On the seas and in the air the Canadian Navy and Canadian Air Force fought right from the earliest stages of the War; to the point where, almost from a zero start, the Canadian Navy and Air Force were the 3rd largest in the world by the end of the War.

The Canadian War effort was forcefully brought home to the delegates attending the Convention in Session 7, Saturday afternoon October 13th. The room was packed with people waiting to hear from four people who all had a part to play in Churchill theatres of war, one might call it. The panel included former Prime Minister John Turner who was too young to enlist but when he was a boy of 12 years met Prime Minister Winston Churchill in Ottawa minutes after his famous ‘Some Chicken Some Neck’ speech, December 30th, 1941. Winston had just emerged from the equally famous Karsh photo session in the Speakers Office and walked outside on that chilly day to meet the public who had listened to the speech by loudspeaker. Mr. Turner has given a fine account of that meeting, blow by blow, in FH 154. Ottawa was certainly the centre of the Canadian War effort, as most political decisions were made there pertaining to the War.

The other theatres of war in which Canada played a major role saw Sergeant Major George MacDonell leading his troops in Hong Kong, and, after a hard fought campaign, spend four years as a POW in Japan. George told his story, and the audience hung on every word as he described the battle. He complained of the shortcomings of the high Canadian command in Ottawa, the wrong-headed Generals who thought in both Ottawa and London that they could hold on to the impossible. ” And when we were attacked, at the same moment Pearl Habour was attacked, our two Regiments of 2,000 men went into battle. Early on, Churchill sent from London a personal order to the soldiers of the Hong Kong Garrison. It was short and to the point. He ordered us to ‘fight for every inch of ground. Damage and delay the enemy in every way possible, fight to the last round and do not surrender.’ During the battle, the Canadian defenders took Churchill’s orders to heart and they fought, as he ordered, for every inch of ground, and they refused to surrender. By Christmas Day, the still defiant Canadians were isolated on the Stanley Peninsula with an ever-shrinking perimeter and with their backs to the sea. On that day, the Governor of the Island, Sir Mark Young, surrendered the garrison to the Japanese. When the Canadians refused to surrender, hours later the Governor sent us a special written order by hand, ordering us to immediately lay down our arms. And so ended the Battle of Hong Kong, a complete and unnecessary military disaster and a waste of scarce resource. Some 500 Canadian Soldiers, following the battle and nearly four years of cruel imprisonment, never returned home. The Canadians, when charged with a hopeless task on a mountainous island that could not be supplied, evacuated or reinforced, 12,000 miles from home, demonstrated undaunted courage and unswerving loyalty to their country and their British allies. It is not a story about how they failed at Hong Kong but how they succeeded in that bloody conflict to show the world the mettle of which they were made. As we look back on these events, it appears not even Churchill could save us from ourselves, and it is easy for me to understand why sometimes Churchill had so little confidence in generals.” With that sum-up, George MacDonell received a standing ovation.

Lt. Jack Rhind arrived in Italy with the Canadians, in charge of an artillery officer in charge of B Troop. Jack kept a diary, against all orders prohibiting, and read to the audience excerpts from it. ”April 25th – Got out to inspect the result of last night’s shelling, Discover that the shell that woke me up had landed three feet behind our command post.” It is the night of May 11th, a few days after my 24th birthday. We have been given gun programs showing the zero hour is 2300 hours. My diary records the build-up. Then, at that special moment in time when I order ‘Fire’ to my small troop of four guns: “Suddenly the silence is shattered by a deafening roar and the sky is lit up by the flashes of hundreds and hundreds of artillery pieces of all sizes – our 25 pounder field guns, 4.5s, 5.5s, 105s, and even American ‘long toms’. The pandemonium is indescribable. I know that this makes the famous barrages of El Alamein and the Sangro look like small fireworks displays. Sometime around midnight, Jerry starts to toss them over at us. At 0230 hours, he lands a direct hit inside #2 gun pit. By an amazing stroke of luck, no casualties to either the gun or the gun crew. At that moment the gun crew were in a dugout beside their gun as they were having their hourly rest. “Jack described how the ground shook. Every person in the room could imagine what he was seeing and feeling at Monte Casino that day, and that was just one day of months and months fighting up the length and breadth of Italy.

General Richard Rohmer, a young Mustang reconnaisance pilot watched the build up for the Normandy landing, and took pictures in the days later that showed the building of Port Winston, the Mulberry Harbour at Arromanches. It was Richard’s job to swoop in after a sortie, or a battle, to capture the pictures for the fight planners. Often in harm’s way, his plane took its share of shots and flak. In one incident he spotted a German staff car racing out of Caen and swooped in to capture the scene on film and called in to HQ the location. That brought a swift response team of Spitfires that strafed the car and it overturned, killing the driver and injuring the passenger. That passenger was none other than General Erwin Rommel, Military Commander in Normandy, who was so injured he was invalided home for recovery, and never returned to command German troops in the defence of Normandy. Showing the pictures he had taken of the Mulberry Harbours nearly 70 years ago, provided the audience with the feeling of being there.

Indeed the entire presentation of these theatres of War that had felt so much the touch of Winston Churchill, made the entire audience appreciate what it was like to be there. Their first hand stories were acknowledged by half a dozen standing ovations – and people spoke of having tears in their eyes as they listened. As the title of the Session said, “We were there” – and so they were!

Gordon W. Walker, Q.C., was moderator of the Session 7 panel. A director of International Churchill Society – Canada, Mr. Walker has a business and political past having been a Minister in the Government of Ontario, and a Commissioner of the international Joint Commission between Canada and United States.

Photo above courtesy of Gordon Walker. Pictured: Rt. Hon John Turner (former Prime Minister of Canada); Jack Rhind, a Lieutenant in the Canadian Army in Italy; George MacDonell, a Sgt. Major at the capture in Hong Kong of Canadian forces defending the island on Christmas Day 1941; and General Richard Rohmer, then a Flying Officer of a Reconnaissance Mustang on D Day.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.