StoryLine

Chancellor of the Exchequer

Winston Churchill, Parliament Square, London © Sue Lowry & Magellan PR

January 1, 1970

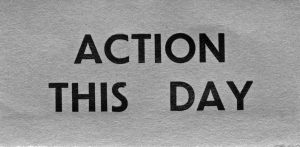

As one of the main architects of New Liberal social reforms, Churchill had established himself as a prominent reforming politician in the earlier years of his career. When Churchill returned to the Conservative party in 1924, Stanley Baldwin, keen to be associated with moderate social reform, promoted him to Chancellor of the Exchequer. He took up the position in November 1924.

Churchill’s period as Chancellor was one of the happiest and most settled phases of his career. He was almost at the top – and, more importantly, had equalled his father’s highest achievement.

Happy he may have been, but he was responsible for restoring the pre-war system of the gold standard – at the pre-war rate of $4.86 to the pound. Even though he consulted widely, he had doubts about the wisdom of returning to the gold standard. But it was seen as a move to pre-war stability and he was responsible for making the final decision. He later came to regard this as one of the most disastrous mistakes of his political career. The economist John Maynard Keynes certainly thought it a bad move and wrote a pamphlet called ‘The Economic Consequences of Mr Churchill’ criticizing the decision.

The consequence was an overvalued pound, damaging effects on British exports and, eventually, the General Strike of 1926. It contributed to the severe depression which followed the Wall Street Crash in 1929 and the British government was forced to abandon it at the height of economic crisis in 1931.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.