Finest Hour 175

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – Royal Revels

April 10, 2017

Finest Hour 175, Winter 2017

Page 42

Review by Sonia Purnell

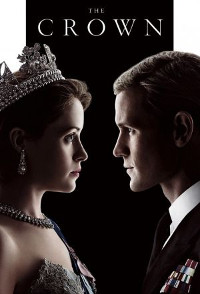

The Crown, season one, produced by Left Bank Pictures and Sony Pictures Television, distributed by Netflix, initial release date 4 November 2016.

Sonia Purnell is the author of First Lady: The Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill (2015). Her article about Clementine starts on page 17.

The words exchanged at the weekly audience between the British monarch and her prime minister are meant to remain private in perpetuity. It is all part of the mystique and majesty that make the British monarchy probably the best known but least understood institution in the world.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Very occasionally the royal door is opened a little—Tony Blair was once indiscreet about an exchange he had had with Queen Elizabeth II on the subject of Princess Diana’s funeral. A predecessor described the Queen during these encounters at Buckingham Palace as “friendly” but certainly not a friend. Historians remind us that as a constitutional monarch the Queen has only three rights—to be consulted, to encourage, and to warn—and it is likely that she exercises all of them, particularly in these troubled times.

Yet even with such meagre fare, Peter Morgan offers us a credible depiction of Winston Churchill’s audiences with the Queen in the new Netflix series The Crown. Skillfully Morgan plots the transformation of a privileged, under-educated, flesh-and-blood young woman into a monarch anointed in an abbey and answerable to God—a journey of self-sacrifice and personal transformation in which Winston Churchill, her first premier, is one of her greatest guides.

The fact that a TV series aims to deal with such difficult and thought-provoking themes is admirable. That The Crown avoids both mawkish sentimentality and bodice-ripping sensationalism is even more so. But then Morgan’s talent for telling history through entertainment has been evident ever since he first launched his play The Audience onto the West End stage in London a few years ago starring Helen Mirren as the Queen.

With excellent understatement, Claire Foy shows us how the monarch’s identity is split down the middle. There is the human Elizabeth, the wife, mother, and sister; and there is Elizabeth Regina. When these come into conflict, the Crown must always win. It is Churchill’s job to remind the young Queen of this until she understands it fully herself. At that point he can lay down his burden at the age of eighty and leave his beloved Downing Street forever; the young Elizabeth was then only just embarking on the vocation that still sees her doing her royal duty at ninety.

The American actor John Lithgow, who plays Churchill, impresses with his mastery of British cadence, and does not overdo the Churchillian drawl. He perhaps exudes too much sadness in his part’s latter years—even when frail, Winston reveled in mischief and wit. Lithgow is also too tall for the role—his silhouette reminds more of Churchill’s grandson Sir Nicholas Soames than the five foot eight inches of the legendary war leader.

Harriet Walter is physically more suited to her part as Clementine, Churchill’s willowy, supportive, and long-suffering wife. For once, we get a taste of just how involved, intelligent, and inventive she was. No wonder there has been such a wave of interest in Clementine since The Crown was launched—she is the only other female character apart from the Queen who steals scene after scene.

For all Peter Morgan’s astonishing talent for handling very real issues, The Crown is, however, drama, not documentary. Prince Philip, portrayed here as a petulant cad, may well have been frustrated by the constraints of his position in the early days and the loss of his naval career. He certainly enjoys risqué jokes and admiring beautiful women, but he has remained a stalwart support to the Queen and ploughed his own furrow with investigations into the living conditions of factory workers and the hugely popular Duke of Edinburgh Award scheme for helping children enjoy the great outdoors and many other interests.

There also seems no foundation to the The Crown’s hint that the Queen may have dabbled with Lord Porchester, who shared her passion for horses and became her racing manager in 1969. Nor is there substance to the suggestion that the Queen betrayed her sister Princess Margaret by initially appearing to support the proposed marriage to the divorced Group Captain Peter Townsend, and then eventually forbidding it. Official papers reveal that the monarch actually drew up plans with Churchill’s successor Anthony Eden that would have allowed Margaret to marry, keep her royal title and allowance, but renounce her rights of succession. The fact is that Margaret and Townsend simply grew apart.

The Crown, then, is novelised history and an entertaining one. Yet its bold handling of real themes such as duty and heartache lift it beyond any typical, beautifully-shot period drama to a modern art form dealing with timeless truths.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.