Finest Hour 179

Churchill on Screen: The Five Best

Brendan Gleeson as Winston Churchill, Into the Storm

January 20, 2018

Visitors to Chartwell and Chequers during Winston Churchill’s time were often treated to film screenings hosted by one of the premier cinephiles of his era. Whether in or out of power, Churchill turned to movies for entertainment, relaxation, and inspiration. “He loved the films, any film,” recalled one of his private secretaries. “After it, then tears down his face, and wiping them away, “The best film I’ve ever seen.”1

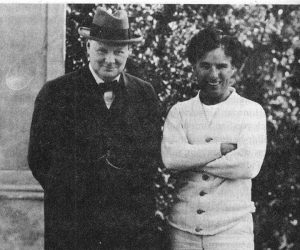

Churchill knew something about the film industry. Not long after the end of his time as Chancellor of the Exchequer following the defeat of the Conservative government in 1929, Churchill found himself in Hollywood, where he visited Charlie Chaplin and was filmed with the diminutive actor at his studio. Churchill also pursued the very modern practice of writing screenplays for movies that were never made, a lucrative sideline that helped keep at bay the ever-present creditors that so haunted his middle years. Perhaps his most intriguing cinematic near miss was an epic film about Napoleon, which was to feature Chaplin in the lead role.

As we imagine him gazing time and again upon the silvery images of his favorite film, That Hamilton Woman, eagerly watching Laurence Olivier as Admiral Nelson lead his country to victory at Trafalgar, one wonders whether Churchill envisioned himself as a character in the films of the future perhaps inspiring some president or prime minister yet to come.

That has certainly come to pass. Churchill has been depicted on screen more than sixty times, usually in supporting roles, and often on television, a medium he abominated. Of these productions, about a dozen feature Churchill as the lead character. In a remarkable coincidence, two of them were released in theatres last year. One was the worst Churchill film ever made (Churchill, starring Brian Cox), and the other the best. (2017’s other major film about the Second World War, the riveting Dunkirk, which climaxes with a reading by an exhausted soldier of Churchill’s famed “Fight on the Beaches” speech of 4 June 1940, did not depict the prime minister.)

2024 International Churchill Conference

Recognizing that even the most enthusiastic Churchillian has only a limited amount of leisure time, it seems a useful exercise to identify the movies and television dramas about Sir Winston that, because of great performances, high production values, and relative historical accuracy, are most worth watching.

So let us count down, in reverse order, the five best films ever made featuring Winston Churchill as the principal character.

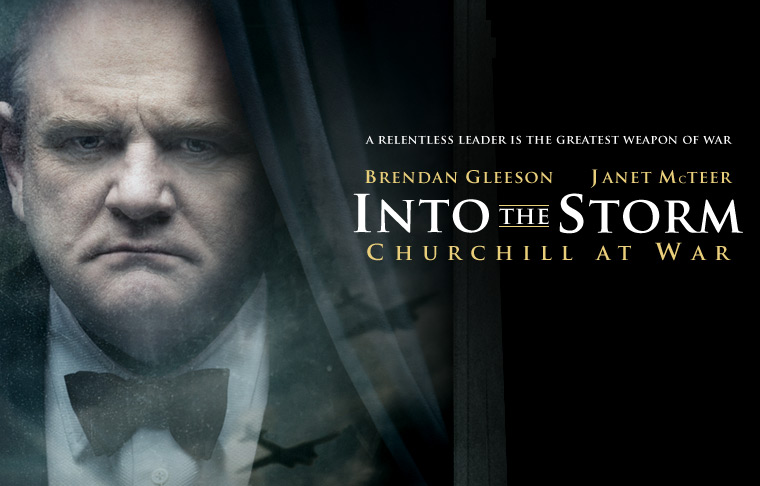

5) Into the Storm (2009)

The gifted, bearlike Brendan Gleeson took on the role—the only Irishman yet to do so—in this sequel to 2002’s The Gathering Storm. It depicts Churchill from his elevation to the premiership until his summary dismissal by the electorate in 1945. The film is handsomely shot and generally well acted, and Gleeson acquits himself rather well as the wartime prime minister. Though much taller and broader than the real Churchill, Gleeson adopts a posture and demeanor that effectively embody the great man. (In this he far exceeds another oversized Churchill actor, John Lithgow, who often seemed to bend over double in the 2016 Netflix drama The Crown in order to compensate for being nearly a foot taller than the character.)

There is a particularly moving scene in which Churchill presents a Victoria Cross to a young airman, who is gradually revealed to have suffered terrible facial injuries. “You feel very humble and awkward in my presence, don’t you?” asks the prime minister. “Yes, sir” he responds. “Then you can imagine how humble and awkward I feel in yours.” Such uplifting scenes alternate with others that depict a leader filled with private doubts and fears, and lashing out at family and staff.

Set against the film’s great qualities is the rushed and episodic nature of the production, the inevitable result of trying to fit the five tumultuous years of Churchill’s leadership into an hour and a half. The sudden shifts from the spring of 1945, as Churchill and his wife holiday in France while awaiting the results of the general election, to various points in the war—and back again—are confusing to viewers unfamiliar with these events (a problem unlikely to afflict readers of this publication). Into the Storm is an earnest, sincere, and enjoyable production, but also a reminder that the best and most dramatically satisfying “biopics” are those that focus on a relatively narrow slice of the subject’s life.

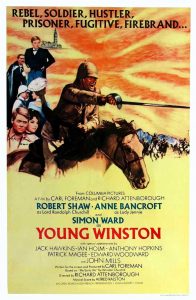

4) Young Winston (1972)

Young Winston is an old-fashioned epic based on Churchill’s charming 1930 autobiography, My Early Life, and starring Simon Ward in the title role. The film is directed by Richard Attenborough and features Robert Shaw and Anne Bancroft as Lord and Lady Randolph Churchill. (In an odd portent of things to come, Robert Hardy plays Churchill’s sadistic schoolmaster.) It opens on the Northwest Frontier and gallops round the world in the wake of its eponymous hero.

With his slender frame and round face, Simon Ward is a convincing, if somewhat idealized version of Churchill. He expertly portrays the supremely ambitious “medal-chaser” so derided by his senior officers, and the budding statesman taking his first steps as a parliamentarian. While the film is mostly a forthright celebration of youthful heroism, it is surprisingly frank about Lord Randolph’s final illness (though remarkably chaste about Lady Randolph’s amorous adventures).

Although Churchill secured his fortune by selling the film rights to many of his books (See David Lough’s article in FH 174 “Churchill and the Silver Screen”), this was the only one that made it to the cinema. Young Winston was not only the first major theatrical release about Churchill, it was the last until 2017.

3) The Wilderness Years (1982)

This eight-part television miniseries, produced by Southern Television and broadcast on ITV, had the enviable distinction of having Sir Martin Gilbert, Churchill’s official biographer, as historical advisor. His careful, scrupulous hand is in evidence throughout, as Churchill’s lost decade unfolds at a stately pace. The vicissitudes of the British governments in the 1930s have never been so thoroughly and accurately dramatized.

Robert Hardy was the definitive Churchill for a generation of admirers. He played the role in more productions than any other actor and expertly embodied Churchill’s fighting spirit, restless ambition, and rolling cadences. Hardy also had Churchill’s mannerisms down pat. As a longtime honorary member of ICS, Hardy also performed Churchill in person as he did at the Blenheim Conference in 2015 when he and Churchill’s granddaughter Celia Sandys took turns reading from the letters of Winston and Clementine.

The ensemble cast of The Wilderness Years features many great character actors from the era including Nigel Havers as Randolph Churchill, Peter Barkworth as Baldwin, Eric Porter as Chamberlain, Peter Vaughn as Sir Thomas Inskip, and the always engaging Frank Middlemass as an appropriately snobbish Lord Derby. Sian Phillips is perhaps too hard-edged as Clementine, lacking her ethereal grace, and the young Tim Pigott-Smith seems to shout all his lines as Brendan Bracken. But Edward Woodward brings suave urbanity and veiled menace to the role of arch-appeaser Sir Samuel Hoare.

Hampered in part by the cheap film stock typical of the era and a less than spectacular DVD transfer, the film has a somewhat dated look. Though hardly a fault, it requires a much greater investment of time than any of the other films on this list. Yet in its encyclopedic scope, its expert navigation of the stormy political seas of the 1930s, and its strong lead performance, The Wilderness Years will always deserve a prominent place in the annals of Churchill on film.

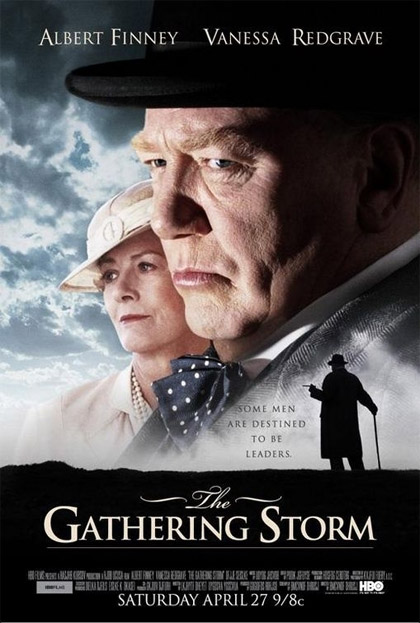

2) The Gathering Storm (2002)

Never in the field of television movies have so many fine actors done so much good work over such a short running time. In this joint BBC/HBO production, Albert Finney excels as Churchill (though he appears much older than Churchill was at the time), as does the exquisite Vanessa Redgrave as Clementine. But they are merely the leading lights of a truly sublime cast; even the smallest roles are filled with actors of the highest caliber. From Sir Derek Jacobi as Stanley Baldwin, to a then-unknown Tom Hiddleston as Randolph Churchill, to Linus Roache and Lena Headey as Ralph and Ava Wigram, Tom Wilkinson as Sir Robert Vansittart, and Jim Broadbent as Desmond Morton, the viewer is dazzled by the concentration of acting talent.

Superbly directed by Richard Loncraine, the film is a feast for the eyes from the very first frame. The only real fault of the film is that there is not enough of it: Churchill’s wilderness years are squeezed into ninety minutes that fly by too quickly. Though Stanley Baldwin is prominently featured as Churchill’s bête noir, Neville Chamberlain never appears—only his (real) reedy voice is heard announcing: “this country is at war with Germany.” The final scene, in which Churchill professes his gratitude to Clementine for her love and devotion before returning to the Admiralty in 1939, the majestic score swelling to a crescendo in the background, is profoundly moving.

The Gathering Storm is the loveliest evocation of the somewhat chaotic idyll that was Chartwell in the 1930s since the lyrical preface of William Manchester’s second volume. As much a domestic drama as a political one, it memorably and succinctly evokes the difficult years of Churchill’s political exile, when his marriage was under its greatest strain, and culminates in a rousing personal and political triumph.

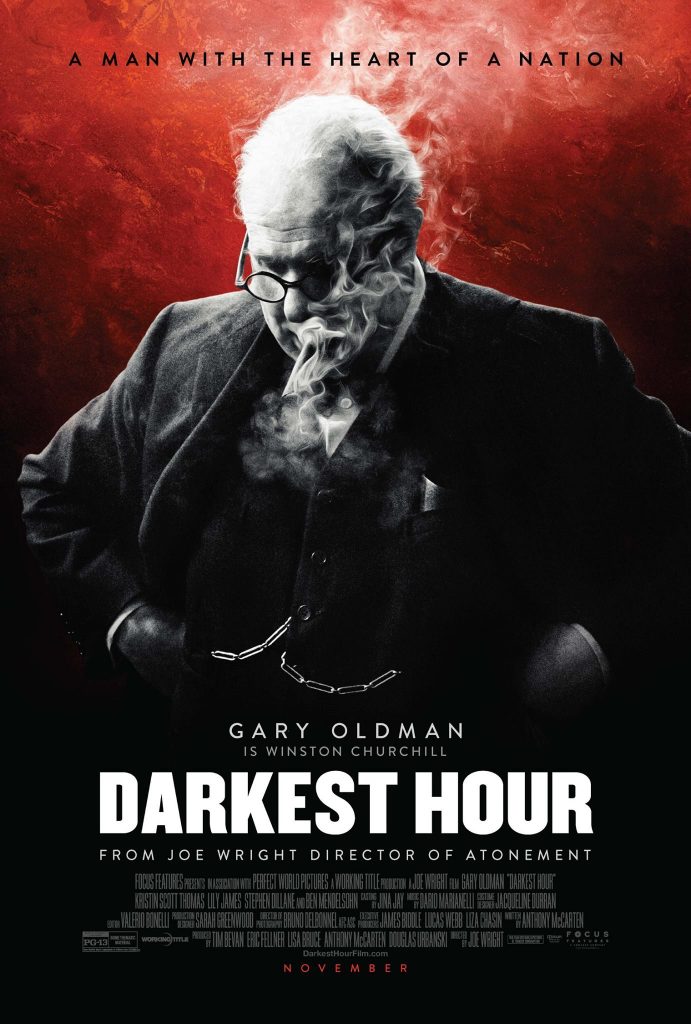

1) Darkest Hour (2017)

The latest incarnation of Churchill on screen is also the greatest. The slender, working-class Gary Oldman, who shot to fame playing Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols in Sid and Nancy, seemed an unlikely choice when his casting was announced in 2015. But to film buffs and his fellow thespians, Oldman is known as one of the greatest actors in the world, a chameleon-like performer who has brought to life such disparate characters as Lee Harvey Oswald, Ludwig von Beethoven, and John le Carre’s master spy George Smiley. I have written elsewhere about the greatness of Oldman’s performance (FH 178); at the time of this writing, he has already collected numerous awards for his portrayal of Churchill including the Golden Globe, and is an Oscar favorite. Like Daniel Day-Lewis in Lincoln, Oldman immersed himself in the character, eerily channeling his voice, mannerisms, and explosive energy.

The near-total physical transformation of Oldman into Churchill achieved by the supremely gifted makeup artist Kazuhiro Tsuji removes the most important roadblock preventing most viewers from being absorbed into historical drama: the obvious fact that they are watching a famous and recognizable actor impersonate a historical figure. Oldman’s invisibility makes the drama all-enveloping. Darkest Hour is by no means a documentary, but on occasion the Churchill in the film and the Churchill in the newsreels are all but indistinguishable.

Kristin Scott Thomas is perfect as Clementine Churchill: elegant, feminine, and strong, and an essential partner to her mercurial husband. Ben Mendelsohn is first rate as King George VI, and both Lily James and Stephen Dillane turn in strong performances as, respectively, Churchill’s semi-fictional secretary and the very real foreign secretary Lord Halifax.

Director Joe Wright brought the beaches of Dunkirk to vivid and unforgettable life in his previous film Atonement and here employs truly creative framing and staging to convey Churchill’s isolation and eventual triumph.

Anthony McCarten’s script is smart, snappy, and well researched, though his fictional detour into the London Underground with Churchill will leave some viewers rolling their eyes. But McCarten deserves every plaudit for focusing the screenplay on the most important few weeks not only of Churchill’s life, but arguably of the twentieth century: the beginning of his wartime premiership when Hitler was sweeping all before him and the British establishment was eager to secure a compromise peace with the dictator. This decision not only makes the film more tightly focused and suspenseful, it conveys to a new generation the real reason why Churchill is the greatest and most important leader of modern times.

On 11 January 2018, Darkest Hour was screened before a select audience in the State Dining Room of 10 Downing Street. Somewhere, Churchill must have been smiling.

Endnote

- Martin Gilbert, In Search of Churchill: A Historian’s Journey (London: Harper Collins, 1994), p. 312.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.