Finest Hour 170

Churchill’s World – Lord Randolph Churchill’s Legacy: Shares not “Sacks” of Gold

December 3, 2015

Finest Hour 170, Fall 2015

Page 18

By David Lough

Lord Randolph Churchill died in January 1895 at the age of forty-five. His son Winston Churchill claimed thirty-five years later in his autobiographical volume My Early Life that Lord Randolph had died “at the moment when his new fortune almost exactly equaled his debts.”1 Ever since historians have usually accepted this verdict.2

It is true that Winston’s parents had struggled with money all their married lives. The Churchill and Jerome families had contributed enough assets to the young couple’s marriage settlement to put them in the top percentile of Britain’s income earners at £3,000 a year; in addition, Lord Randolph’s father, the seventh Duke of Marlborough, gave them an extra £10,000 with which to buy a London house.3

Yet this start had never been enough to satisfy the expensive tastes that Lord Randolph and Jennie Jerome had acquired in their youth: Jennie could no more give up buying her clothes from expensive designers in Paris than Lord Randolph could cast off the male Churchills’ fondness for gambling.

The couple soon resorted to borrowing, first from the Standard Life Insurance Company and then from more unofficial and expensive moneylenders. The situation improved in 1883 when the Duke of Marlborough died and left his personal assets in trust for eventual inheritance by his second son. On the strength of the will, Lord Randolph was able to reduce his borrowing costs by consolidating all his debts, now at £30,000, with the more keenly priced Standard Life.

The Mercurial Politician

Two years later, in 1885, his finances improved again on his appointment to the post of Secretary of State for India in Lord Salisbury’s Conservative cabinet: the ministerial salary amounted to no less than £5,000. The relief lasted only until the end of the year when William Gladstone’s Liberal party regained power. Seven months later, however, in the election of July 1886, Lord Randolph played a decisive role in ousting Gladstone permanently from power and was rewarded by Lord Salisbury with the much more powerful position in his new government of Chancellor of the Exchequer.

A cautious chancellor could have expected his position—and salary—to last for several years, but by the end of the year Lord Randolph had overplayed his political hand once too often in his attempts to force a reduction of military expenditure. Salisbury unexpectedly calmly accepted a rash resignation by his chancellor, leaving Lord Randolph once more without gainful employment.

His attempts at political rehabilitation encountered growing difficulties as a result of ill health. He suffered from a progressive illness (treated by his doctors as syphilis) that entailed long absences from Westminster and made it even more difficult to keep his wife Jennie and young sons Winston and Jack (aged eleven and six when their father resigned) in the style to which the family had become accustomed.

For as long as he could, Lord Randolph displayed the Victorian aristocrat’s disdain for the world of business and money: almost four years after his resignation, he still felt able to turn down the offer of £2,000 a year to act as chairman of an American mining company in London.4

The Rothschilds

It was one of his friends in the money world, Lord Rothschild, who in 1891 eventually found a solution that was socially acceptable to a duke’s younger son. A friend since their schooldays together, Nathaniel Rothschild suggested that Lord Randolph should assemble an investment syndicate to finance a gold prospecting expedition that he would lead to southern Africa, with the Rothschilds providing banking and logistical services. Southern Africa formed the metal’s fashionable new frontier at the time, yet still accounted for less than one per cent of world gold production.

Many forecast that this share would rise sharply once explorers reached new territory such as Mashonaland (later Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe) or succeeded in mining at greater depths. Alfred Beit, a German-born mining engineer and financier who was close to the Rothschilds, argued that deeper mining would prove the more fruitful strategy (he had just bought properties in the Central Rand and was eyeing the Witwatersrand region near Johannesburg). The Rothschilds, however, wanted Lord Randolph to concentrate on Mashonaland.

The expedition’s budget required Lord Randolph to raise at least £12,000 from investors. The Rothschilds lent him £4,000 so that he could take a personal stake of one-third, but Lord Randolph succeeded in raising a further £11,000 from “family and friends.” To keep his share close to one third, he borrowed another £1,000 unofficially, taking the final amount raised to £16,000.5 Amongst the contributors was another of his school friends, Algernon Borthwick, whose family owned the Morning Post and Daily Graphic newspapers. Borthwick not only invested in the syndicate but commissioned Lord Randolph to write a series of twenty reports on its progress for their newspaper at a personal fee of £100 per report.

The fund-raising phase complete, Lord Randolph transferred £2,000 to his own bank to help pay for personal equipment: according to the Weekly Dispatch, this included twenty-five cases of champagne.6 Initially he also agreed to take a new gold-washing machine patented by his brother-in-law Moreton Frewen, but at the last minute he decided that the machine was another of Frewen’s improbable ventures and left it behind along with its inventor. Instead he took the more conventional services of the Rothschilds’ recommended mining engineer, Harry Perkins, and their logistical expert, Captain George Giles.

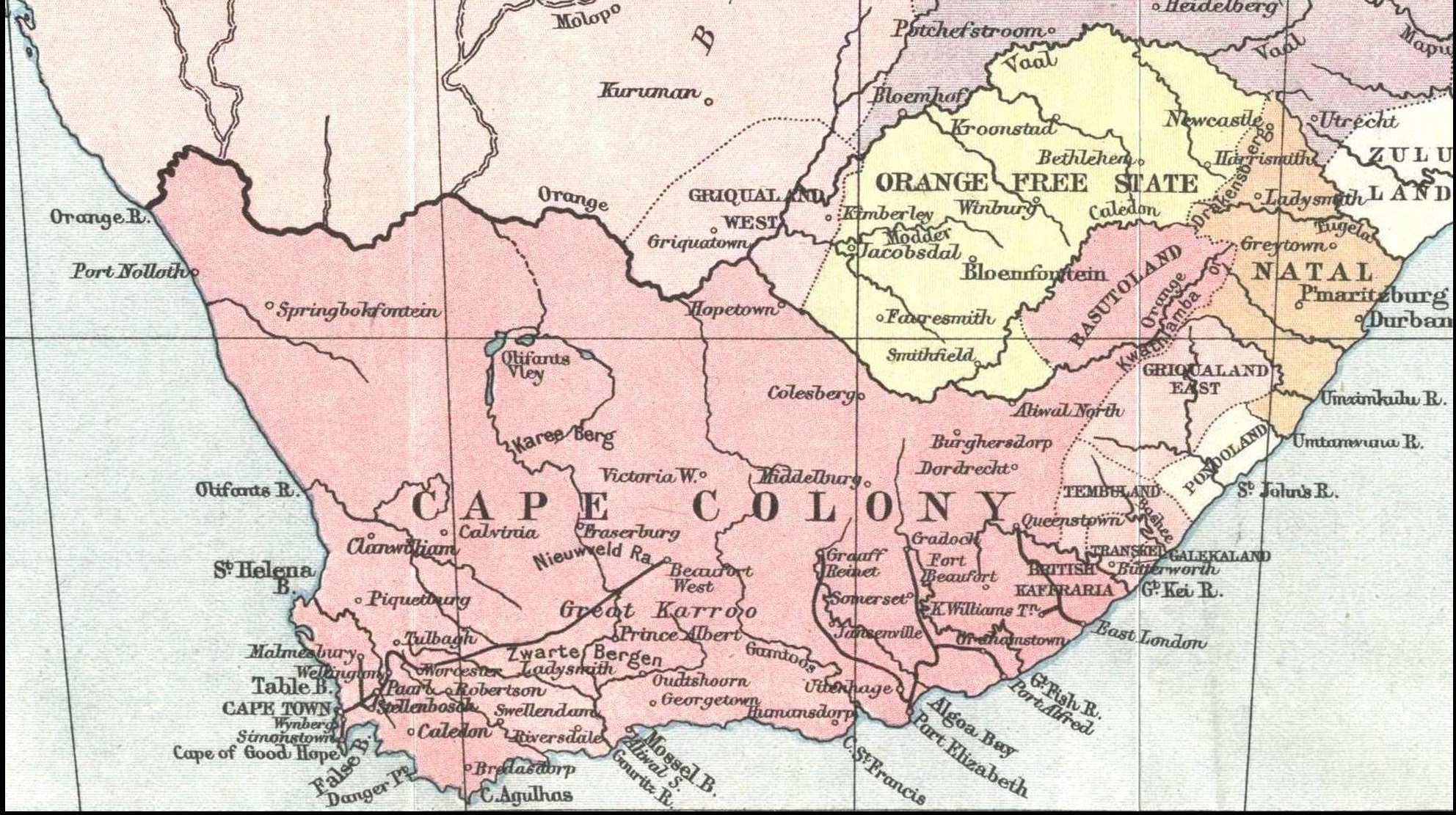

South Africa

On arrival at Cape Town in April 1891, Lord Randolph carried a Rothschild letter of credit for £10,000 to cover local expenses.7 He found to his alarm that supplies would cost “nearer 4000£ than two” and decided to join forces with two syndicates that had already arrived to stake out mining claims in Mashonaland. The combination added four more Europeans (each with a manservant), a French cook, four native grooms and twelve native drivers to a party that was already accompanied by ninety oxen (to pull five ox-wagons), twelve mules, twelve donkeys and eight horses.8 “The business affairs of my amalgamated syndicates out here are not altogether satisfactory,” an anxious Lord Randolph wrote home. “Very much more money has been spent than I or the people in London had any idea of.”9

While the main party set off for the diamond mines of Kimberley, Lord Randolph stayed in Cape Town to discuss politics and invest £1,000 of the syndicate’s spare funds in the mining company De Beer. He rejoined his colleagues for the five-day march to Johannesburg, where he temporarily invested the rest of the surplus in gold stocks traded either on the local stock exchange10 or on London’s so-called kaffir market for southern African companies, asking his friend Oliver Borthwick to buy “Transvaal Silvers” and “Nigels.”11

Back home in London, Jennie was finding money so tight that she put the family house up for sale and moved with Winston and Jack first into her sister Clara Frewen’s home and then into the dowager Duchess of Marlborough’s larger house in Berkeley Square. “How I long for you to be back with sacks of gold,” she wrote to Lord Randolph.12

It was not to be. The travelling arrangements of her husband’s party became something of a local joke as they took six weeks to travel from Johannesburg to Fort Salisbury, the capital of Mashonaland. “The wonderful thing was that they could never buy enough,” wrote the experienced African traveller Percy Fitzpatrick. “They put in some supplementaries at Cape Town, and some ‘after-thoughts’ at Kimberley, and etceteras at Johannesburg, and extras at Pretoria, and replenishments at Pietersburg, till they looked like the commissariat of a continental army.”13

Once they reached Mashonaland and started to prospect, it became clear that there was little gold. Perkins, the mining specialist, found only one feature, the Matchless, which held out real promise: Lord Randolph spent £2,000 to buy a half-share and fund efforts to mine it more deeply.14 Two weeks later he reported to Jennie that it could be worth “a quarter to half a million” pounds if the mining grades held up at lower depths.15 But soon afterwards the Matchless filled with water and had to be abandoned.

The expedition team started its long march back to Cape Town with only a profit of £1,000 on Lord Randolph’s Johannesburg investments to show for its efforts.16 The London share purchases were still rising in value, so Lord Randolph persuaded the Rothschilds to lend the syndicate an extra £6,500 so that he could keep the London shares for longer while he settled local bills before leaving Africa. He waited for a year after his party’s return in January 1892 to sell the last of the shares; nevertheless the syndicate’s final accounts at Rothschild show that its investors lost every penny.17

The Family Nest Egg

Lord Randolph, however, fared better. Not only did he receive £4,000 for his reports to the Daily Graphic plus his expenses, he also gleaned vital intelligence about the Transvaal’s gold prospects that convinced him to take advantage of a private investment opportunity offered by Alfred Beit. Beit invited both Lord Randolph and the Rothschilds to buy shares in his new Witswatersrand mining company, Deep Levels, at a privileged price of five shillings per share before its planned public stock market flotation.18 Lord Randolph diverted his mining experts to take a closer look at the area during the march back to Cape Town and, on the strength of their report, borrowed £1,250 to buy 5,000 shares.

This single transaction was to fund his family for the short balance of his life and help him to leave a substantial legacy. Deep Levels’ share price rose appreciably even before its public flotation, allowing the Rothschilds to lend Lord Randolph growing sums after his return to England; then, once the shares floated on the public markets in 1893 (becoming known thereafter as Rand Mines), he was able to sell parcels of them to produce cash. He raised £2,000 in October 1893 by selling 500 shares at £4 each and £1,100 in February 1894 by selling another 200 at £5 12s. each.19

The kaffir share boom continued throughout 1894: several hundred brokers and market-makers carried on trading outside the Stock Exchange each day after it closed. “In clubs and trains, in drawing rooms and boudoirs, people are discussing ‘Rands’ and ‘Modders,’” financial journalist S.F. Van Oss reported. “Even tradesmen and old ladies have taken to studying the Mining Manual, the rules of the Stock Exchange, and the highways and byways of stockbroking.”20

Estate Settlement

As quickly as the Rand Mines share price rose during 1894, Lord Randolph’s health was fading. After cutting short a world cruise during the fall, he died on 24 January 1895 at home, still owning 2,300 Rand Mines shares. By then each share was worth more than one hundred times the price he had paid for it three years earlier. As their price continued to rise, his executors waited before selling them through the Rothschilds in two batches: 1,000 on 8 March for £26 each and the other 1,300 on 11 March at £29.75.21

The proceeds from the sales accounted for nine tenths of the value of Lord Randolph’s gross estate, published as £75,971.22 Winston’s claim that his father died when his debts almost equaled these assets is not supported by the evidence of the Rothschilds’ banking ledgers, which survive today in the family’s London archive. Three weeks before Lord Randolph’s death, he owed only £12,758 across all his four accounts at the bank.23 The Rothschilds sent his executors two checks: first an interim one for £2,000; then a second in April 1895, calculated after subtracting all the debts, for £52,237.24

In his will Lord Randolph left Jennie a small cash legacy of £500 and settled the rest of his estate into a trust, to be known for many decades thereafter as Lord Randolph Churchill’s Will Trust. The trust started with capital of just over £50,000, effectively all provided by the sale of the Rand Mines shares. The will stipulated that the income produced by this capital should go to Jennie during her lifetime, then pass equally to their two sons, Winston and Jack. Lord Randolph added a clause, however, to allow his trustees (of whom Jennie was one)25 to divert half the trust’s income to Winston and Jack “after the…second marriage of my said wife.”

The ambiguous wording of this clause left it unclear whether he intended the trustees to consider this move at the beginning or end of Jennie’s second marriage.26 In any event, no one raised the matter when six years later she did remarry, choosing a man of half her own age who had his own financial difficulties.27 Winston and Jack remained unaware of the clause until Jennie’s second marriage ended in 1913. Then an alert young lawyer spotted the clause while carrying out checks for a new loan that Jennie badly needed. Her sons were angry at having been kept in the dark; in the circumstances, however, neither wished to press for a diversion of the trust’s income.

It was not until their mother’s death in 1921 that Winston and Jack took over their share of the income from their father’s trust. Winston soon started borrowing its capital to help defray the cost of modernizing Chartwell. Well before he finished writing My Early Life in 1930, he had tapped it for £12,000.28 It is curious that he should have overlooked this paternal legacy, but money was never Winston’s strong suit.

David Lough is the author of No More Champagne: Churchill and His Money, published in the US by Picador and in the UK by Head of Zeus, 2015.

Endnotes

1. Winston Churchill, My Early Life (London: Thornton Butterworth, 1930), p. 195.

2. For example, R.F. Foster, Lord Randolph Churchill (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981), pp. 394–95.

3. Sterling figures should be multiplied by 100 to reach an approximate 2015 £ value; or by 150 to reach an approximate 2015 US$ value.

4. 14 August 1890, Lord Randolph Churchill (LRC) letter to Lady Randolph Churchill (LyRC), CHAR 28/9/17, Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge (CAC).

5. £2,000 of the syndicate’s funds came from Lord Randolph’s sister Cornelia, who had married into the wealthy steel family, the Guests; his mother, the dowager duchess, and another sister, Lady Sarah Spencer-Churchill, gave £1,000 each; the Marquis de Breteuil and Baron de Hirsch, each long-established European friends of the Jerome family, together gave £1,500.

6. 9 April 1891, Weekly Dispatch, Moreton Frewen papers, Library of Congress.

7. Rothschild 1891 ledger, I/8/13 account 178 Lord Randolph Churcill (LRC) Syndicate Account, Rothschild Archives London (RAL).

8. 16 May 1891, LRC letter to LyRC, CHAR 28/11/9, CAC.

9. 30 May 1891, LRC letter to LyRC, CHAR 28/11/13, CAC.

10. 26 June 1891, LRC letter to LyRC, CHAR 28/11/19, CAC.

11. 17 June 1891, LRC letter to LyRC, CHAR 28/11/17, CAC.

12. 23 September 1891, LyRC letter to LRC, CHAR 1/2/9, CAC.

13. Cited in Brian Roberts, Churchills in Africa (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1970), p. 38.

14. 13 September 1891, LRC letter to LyRC, CHAR 28/11/36, CAC.

15. 29 September 1891, LRC letter to LyRC, CHAR 28/11/39, CAC.

16. 7 November 1891, LRC letter to LyRC, CHAR 28/11/42, CAC.

17. Rothschild 1892 ledger, I/8/14 a/c 178, RAL. The syndicate’s final deficit of £370 was eventually debited by the Rothschilds to Lord Randolph’s estate.

18. David Kynaston, The City of London, (London: Chatto & Windus, 1995), vol. II, p. 83.

19. Rothschild 1894 ledger, I/8/16 account 178/4, RAL.

20. Cited in Kynaston, vol. II, p. 110.

21. Rothschild 1895 ledger, I 8/17 account 178, RAL.

22. The New York Times, 5 March 1895, p. 5.

23. Rothschild 1894 ledger, I/8/16 account 178, RAL.

24. 14 April 1895, Executors letter to A. de Rothschild, 000/134 packet 95 000 182, RAL.

25. The duke of Marlborough and Lord Randolph’s brother-in-law George Howe were the other trustees.

26. Epitome of LRC will 1883, CHAR 1/79/2; full version, CHAR 1/79/5, CAC.

27. George Cornwallis-West, who was slightly younger than Winston.

28. 14 February 1927, Nicholl Manisty & Co. valuation of WSC interests in family trusts, CHAR 1/196/1, CAC.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.