Finest Hour 192

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – A Popular Loser

December 30, 2021

Finest Hour 192, Second Quarter 2021

Page 42

Review by David Freeman

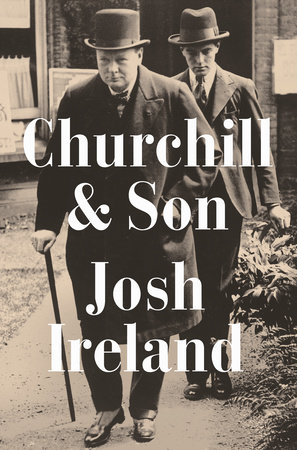

John Ireland, Churchill & Son, 2021, Dutton/John Murray, 453 pages, $34/£15/CAN $45. ISBN 978–1524744458

David Freeman is editor of Finest Hour.

Despite being the grandson of a duke, Winston Churchill shrewdly perceived that his name and pedigree alone would not suffice to launch him onto the serious political career to which he aspired. He therefore spent several years as a young army officer seeking out danger, serving honorably, and writing about his experiences, first in newspapers and then in books. At age twenty-four, he spent an entire year researching and writing his two-volume history of The River War, now available again in print for the first time in more than 120 years. The hard work paid off. By age twenty-six, Churchill was MP for Oldham.

Unfortunately, this valuable example was completely lost on Churchill’s son Randolph. Quick-witted and good looking, Churchill’s only son completely lacked, as Andrew Roberts has observed, even a fraction of his father’s self discipline. He DID try to launch himself into politics on nothing more than his famous name. Along the way Randolph could not even be bothered to finish his studies at Oxford and take a degree, an opportunity that his father never had and assiduously worked to make up for during his soldiering days in India. Randolph also rejected his father’s advice to become a lawyer, the most traditional of all routes into politics.

There have been several biographies before now about Randolph, whose own sister Sarah once described him to his face in a well-meaning way as “a popular loser.” Even friendly biographers such as his son Winston could not disguise the fact that Randolph was an inconsiderate, self-centered boor who never learned to pick his battles wisely. Yet by all accounts he also inspired deep affection in his family and friends, who could never stop loving him even though they found him impossible to live with.

Reconciling the many contradictions, Josh Ireland has produced the most objective and balanced biography of Randolph Churchill to date. He has gone deep into the archives on both sides of the Atlantic, especially the Churchill Archives in Cambridge, and tried to be as fair to his subject as possible—a task probably made easier by being much too young to have met him. Still, readers of Churchill & Son will come away with some idea of what it must have been like for people who did know Randolph to have felt warm feelings for him, even as they learned to keep their distance.

Above all, Randolph aspired to a serious political career. “It was the only life he was interested in,” Ireland writes, and one for which he believed he possessed the sorts of ‘aptitudes & abilities which are granted to few.’” “There is no other Englishman of my age,” Randolph wrote his father in 1947, “who knows this country as well as I do or has so many influential American friends.” That sort of arrogant thinking explains why at age thirty-six he was already a permanent political failure.

Randolph pursued a parliamentary career in a way that seemed calculated to guarantee disappointment. His political acumen was epitomized by his reckless decision to challenge the official Conservative candidate at the 1935 Wavertree by-election. Predictably he split the Tory vote and handed the seat to Labour. He had no more success, however, in his campaigns when he did have the approved backing of his party.

Randolph finally got into Parliament during the war, when an election truce between the parties enabled him to run unopposed. He made only one speech as MP for Preston before going off to serve gallantly overseas, leaving his wife Pamela and their new born son saddled with massive gambling debts. Inevitably he lost his seat—and, inter alia, his wife—in the Labour landslide of 1945. Randolph’s frequent drunken outbursts and tendency to blame those around him for his failures, including his parents, guaranteed that he never returned to the Commons. Michael Foot, the left-wing intellectual and one-time Labour leader, stated that he “had never seen such a spectacle as Randolph on the attack.”

To the extent that someone with his personality could do so, Randolph mellowed somewhat with age. As it became clear that he would never achieve political success, Randolph focused more seriously on his journalism, scoring a notable scoop in 1957 when he reported that Harold Macmillan, not R. A. Butler, would succeed Anthony Eden as prime minister following the Suez disaster. He wrote a delightful memoir, Twenty-one Years, about his charmed youth, and his serious biography Lord Derby: King of Lancashire! convinced his father to entrust him with the responsibility of writing an official biography.

I have often explained to audiences that if Winston Churchill truly drank and smoked as much as people believe, misled by Churchill himself, he would never have lived to be ninety years old. Sadly, Randolph truly did drink and smoke to excess, with the result that he died aged fifty-seven and already looking twenty years older. Nevertheless, he did successfully get the official biography of his father well underway and assembled a talented research team to assist him. Several of these young gentlemen went on to be notable Churchill scholars in their own right, including Sir Martin Gilbert. In the end, Randolph did achieve something of which his father could be proud.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.