Finest Hour 182

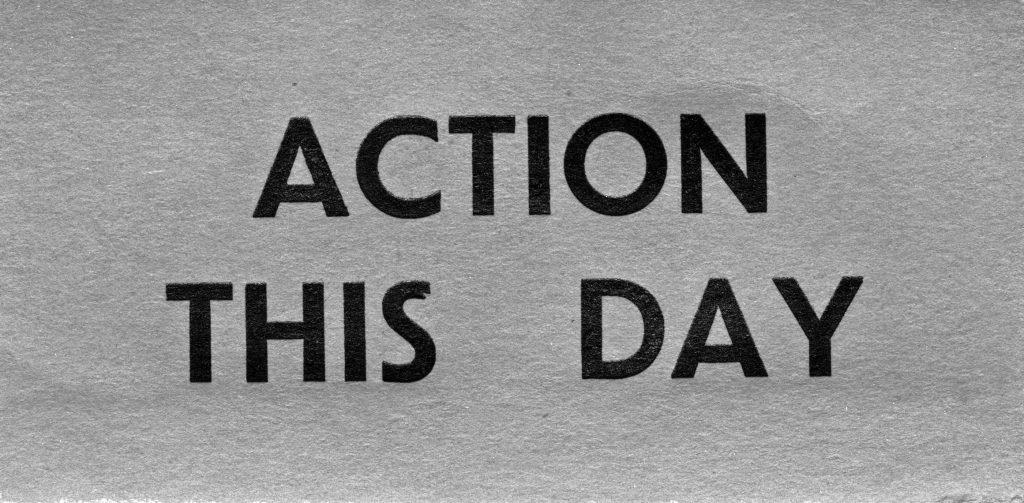

Action This Day – Autumn 1893, 1918, 1943

January 28, 2019

Finest Hour 182, Fall 2018

Page 40

By Michael McMenamin

125 Years Ago

Autumn 1893 • Age 19

“Sandhurst Has Done Wonders for Him”

Once Winston was at Sandhurst, Lord Randolph’s previously caustic attitude towards his son appears to have softened. After taking Winston to Tring, Lord Rothschild’s country estate, Lord Randolph wrote a letter on 24 October to his mother Frances, the Duchess of Marlborough: “I took Winston to Tring on Saturday….He has much smartened up. He holds himself quite upright and he has got steadier. The people at Tring took a great deal of notice of him but [he] was very quiet & nice-mannered. Sandhurst has done wonders for him. Up to now he has had no bad marks for conduct & I trust that it will continue to the end of term. I paid his mess bill for him…so that his next allowance might not be [encroached] upon. I think he deserved it.”

While there is no record that he ever had Lord Randolph’s new-found sentiments expressed to him directly, Winston nonetheless appreciated his father’s changed attitude and wrote in My Early Life that “Once I became a gentleman cadet I acquired a new status in my father’s eyes, I was entitled when on leave to go about with him, if it was not inconvenient.” This included “Tring, where most of the leaders and a selection of the rising men of the Conservative Party were often assembled,” and meeting Lord Randolph’s racing friends, who provided “a different company and new topics of conversation which proved equally entertaining.”

Nevertheless, while Churchill was thrilled to accompany his father (“In fact to me, he seemed to own the key to everything or almost everything worth having”), a more mature Churchill was able to reflect in My Early Life that his father’s attitude had not softened nearly so much as the young Winston would have liked: “But if ever I began to show the slightest idea of comradeship [emphasis added], he was immediately offended; and when I once suggested that I might help his private secretary to write some of his letters, he froze me into stone.”

100 Years Ago

Autumn 1918 • Age 44

“Winston Began Sulky”

While Churchill publicly warned on 7 October against the possibility of “the speedy termination of the conflict,” the Great War was indeed coming quickly to an end, and Churchill knew it. The Armistice was signed the following month.

2025 International Churchill Conference

As Martin Gilbert wrote in Churchill, A Life, “The struggles of war were over, the conflicts of peace had begun.” No one knew this better than Churchill, whose first conflict began a few days before the war ended. His unlikely adversary was his close personal and political friend Prime Minister David Lloyd George.

Deprived as Minister of Munitions of a major policy-making role, without having a seat in the War Cabinet, Churchill was concerned that after the war he would also be excluded from making policy during the peace. This anxiety put him at cross purposes with Lloyd George, who very much wanted Churchill in his peacetime government. But such a government would be a coalition in which Conservatives greatly outnumbered Liberals. Once before, in 1915, the Conservatives had made their participation in a coalition under a Liberal prime minister conditioned upon Churchill’s exclusion from the inner Cabinet and had rebuffed Lloyd George’s initial attempts as prime minister to bring Churchill back into office in 1917. Lloyd George obviously wanted his hands free to dump Churchill again if the Conservatives made it a requirement for their continuing support.

The conflict between Churchill and Lloyd George began on 6 November, with Lloyd George taking the lead. He invited Churchill and Edwin Montagu, the most senior Liberal Party cabinet members, to discuss with him the political future. Churchill was not in the best of moods and, in Montagu’s words, “Winston began sulky, morose and unforthcoming.” When Lloyd George advised the two that he planned to abolish the small five-member War Cabinet at the end of the war and replace it with a larger and more traditional twelve-member cabinet, Churchill’s attitude changed. As Montagu recorded, “The sullen look disappeared, smiles wreathed the hungry face [and] the fish was landed.”

The fish soon dislodged the hook, however, and what followed was an exchange of lengthy correspondence—two from Churchill with one from Lloyd George in between. After a reference to Lloyd George’s “energetic and sagacious leadership” of the war, Churchill’s 7 November letter got right to the point: “It is not possible for me however to take the very serious & far-reaching political decision you have suggested to me without knowing definitely the character & main composition of the new Govt you propose to form for the period of reconstruction….”

Lloyd George was obviously displeased and pulled no punches in his 8 November reply: “After the conversation we had on Wednesday night…your letter came upon me as an unpleasant surprise. Frankly it perplexes me. It suggests that you contemplate the possibility of leaving the Government, and you give no reason for it except an apparent dissatisfaction with your personal prospects. I am sure I must in this misunderstand your real reason for no Minister could possibly adopt such an attitude in this critical moment in the history of our country….”

Churchill seized the lifeline Lloyd George offered him, i.e., that he had misunderstood Churchill’s “real meaning.” He wrote in his 9 November reply that “You have certainly misconceived the spirit in wh my letter was written.” He then referred Lloyd George to a speech he had given on 7 November as evidence of “how far I am from contemplating any ‘desertion’ of you or yr Government….” Churchill concluded his letter with what was really bothering him—the Conservatives’ unrelenting hostility toward Churchill.

In the event, their friendship was restored when, after the 14 December election where Coalition Conservatives and Coalition Liberals received a vast majority, Churchill became Secretary of State for both War and Air in the new Government.

75 Years Ago

Autumn 1943 • Age 69

“If I die, don’t worry—the war is won.”

Autumn 1943 is best remembered for the Big Three Conference in Tehran, when Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin met together for the first time, firmed up plans for the invasion of France in 1944 and more or less settled the post-war eastern boundaries of Poland in the absence of any Polish representatives. What is not so well remembered is that Churchill was unwell throughout the entire fall, including the Tehran Conference, and nearly died in its aftermath.

During the summer, Churchill had journeyed extensively in North America for a series of meetings with President Roosevelt. By the end of September, according to Roy Jenkins, “Churchill was reported by his staff as being tired and bad-tempered.”

Despite his disposition, Churchill was prepared on 7 October to fly to Tunis to meet with General Marshall to discuss Churchill’s Mediterranean strategy to invade the island of Rhodes and plans to bring Turkey into the war on the side of the Allies, and to express new concerns on the perils of Operation Overlord. Marshall was unavailable, so Churchill’s next journey began on 12 November. He was so ill already that he had been unable to preside over a War Cabinet meeting the previous day. Nevertheless, he left for Algiers and Malta, where he disembarked for two days that he spent mostly in bed. It was then on to Alexandria on 21 November and Cairo the day after that. Despite still not feeling well, Churchill went to the airfield to meet Roosevelt’s plane on 22 November. Several days of conferences followed. When Churchill departed for Tehran on 27 November, he had come down with a bad sore throat, doubtless exacerbated by a British dinner for the Americans the night before.

Upon arriving in Tehran, Churchill was so ill that he could not attend a dinner that night with Roosevelt and Stalin. At the conclusion of the Tehran Conference, Churchill flew back to Cairo on 2 December, where a stomachache prevented him from attending a dinner with the Turks. He was now so weak that he could not towel dry himself after a bath. On 10 December, he made an eight and a half hour flight from Cairo to Carthage and slept most of the next day. That night, he was stricken with a severe headache and a fever of 101 degrees. He was soon diagnosed with pneumonia. Jock Colville’s joke on being asked by a new junior secretary what to do in the event Churchill took ill [“You telephone Lord Moran and he will send for a real doctor”] became a reality.

Lord Moran called in specialists from Cairo, Italy, and Britain. On the night of 14 December, Moran thought Churchill’s heart was so weak that the prime minister was going to die. Indeed, Churchill told his daughter Sarah at the time, “If I die, don’t worry—the war is won.” The next day, Clementine was summoned from England, and Churchill suffered a mild heart attack. Clementine arrived on 17 December, and Churchill had another, milder heart attack on the 18th. The patient did not leave his bed until 24 December.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.