Wilderness Years

Churchill Weakened

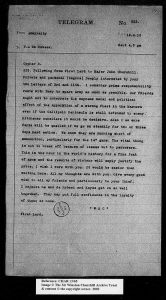

Winston Churchill, Parliament Square, London © Sue Lowry & Magellan PR

March 28, 2017

Those who had felt Churchill’s career had reached its limit when the Conservatives were defeated in 1929 now felt vindicated. Even some of his own party thought Churchill was out of date and out of touch. Rather than weakening Baldwin’s position (as leader), as some thought he’d intended, Churchill – by endeavouring to ‘marshal British opinion’ for a lost cause – in fact, weakened his own position.

When Baldwin and MacDonald joined forces to form a National Government in 1931, bringing together leading figures from the Conservative, Labour and Liberal parties, Churchill’s views on India meant he was excluded from office. With his standing and credibility seriously damaged, this ‘personal crusade without restraint or care for the consequences’ (Ball, Churchill) meant his later warnings about the dangers of Nazism went largely unheeded.

Finding himself increasingly isolated politically, with seemingly little influence, Churchill had time on his hands. He also needed a steady income. Chartwell was an expensive home to run – and he had four children and a wife to support, as well as his ever-lavish lifestyle. He turned his attentions, and prodigious energies, elsewhere.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.