1940-1942

Winter 1942 (Age 67)

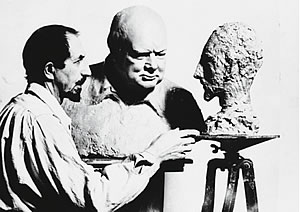

Winston Churchill, Parliament Square, London © Sue Lowry & Magellan PR

March 12, 2015

Churchill and Roosevelt sign the United Nations Charter

On New Year’s Day Churchill returned from Ottawa to Washington where he and Roosevelt signed the United Nations Charter. A few days later he flew to Pompano Beach, Florida, for a short vacation.

While in Pompano Beach, Florida, Churchill visited the home of Edward R. Stettinius, Jr., on Hillsboro Beach for five days in January. Churchill had come to the United States on 22 December 1941, to confer with Roosevelt on the grant strategy of the war. This meeting was known as the Arcadia Conference.

On 5 January 1942, Churchill flew to Florida from Washington for a brief rest.

Churchill has a short stay in Washington and flew on to Pompano Beach, Florida. Churchill flew to Florida in an airplane provided by Chief of Staff General Marshall, accompanying him were Sir Charles Wilson, John Martin and Tommy Thompson. They stayed in a bungalow provided by US Secretary of State Stettinius. They landed at West Palm Beach airport and then drove on to Pompano Beach. Word was put out that a Mr. Lobb, an invalid requesting quiet, was staying at the house. The Prime Minister and his aids were closely guarded during the by the Secret Service during the trip. The press guessed they were there but left them alone.

Churchill to Roosevelt, 6 January 1942

Dear Mr. President,

We have been greeted on arrival by this cutting from the local paper. This shows that all the trouble you took about secrecy has been in vain. Tommy [Detective Thompson] is plainly identifiable.

Yours sincerely,

[signed] Winston S. Churchill

The “cutting” was a cartoon from the Miami Daily News, 5 January 1942 showing two overweight middle-aged men flopped on a beach. The clipping was captioned “Hard work is the thing that will win this war — we must keep at it night and day.”

10 January – Pompano and Fort Lauderdale, Florida. WSC lunched with Consuelo Balsan in Fort Lauderdale before leaving by train for Washington.

Although Stettinius’ home was not then (nor would it be now) within the city limits of Pompano, most of the beach area that is now Hillsboro Beach was commonly referred to as Pompano.

On 14 January Churchill left the United States for Britain. Over the Atlantic he took over the controls of a Boeing flying boat, even making a couple of banked turns.

At a meeting of the War Cabinet Churchill reported that Roosevelt had said to trust him to the bitter end. The next day he told the King that he was confident of ultimate victory.

Dramatic events were taking place on the Eastern Front as the Russians forced Germany to give up the seige of Sevastopol. Hitler attributed this German failure to the severe cold. As desperate as he was for Russian support, Churchill refused to acknowledge Soviet claims to Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

The horror which the Allies were fighting was graphically illustrated at a February meeting in Wannsee, near Berlin, where, in a ninety minute meeting, Heydrich outlined plans for exterminating all Jews in Europe. A month later the first deportees arrived at Auschwitz.

At the end of January the news seemed dark on all fronts. Rommel had become “a kind of magician or bogeyman” to troops in Africa; British forces were being pushed back at Singapore; Churchill faced a no-confidence vote in the Commons. He won the vote with only one dissenter in the Commons and Rommel’s advance was stopped at Libya, but Singapore fell in what Churchill called the greatest military defeat in the history of the British Empire. Nonetheless, Roosevelt, now also in his Sixties, responded to a Churchill birthday greeting: “It is fun to be in the same decade with you.”

Command appointments were being made which would eventually carry the Allies to victory. Stilwell was appointed C-in-C, US Forces in Chinese Theatre; Harris was appointed C-in-C, Bomber Command; Mountbatten was appointed C-in-C, Combined Operations; Slim was appointed C-in-C, Burma; and Blamey was appointed C-in-C, Australian forces. MacArthur left the Philippines with the vow, “I shall return.” Churchill’s dissatisfaction with Auchlinleck in Africa grew.

Concern for Churchill’s burdens and their affect on his health and demeanor grew among his family and associates. His doctor, Charles Wilson, expressed the wish to “put out the fires that seem to be consurning him.” Brooke commented that the Prime Minister was dejected and “in for a lot more trouble.” Mary Churchill noted that her father was “saddened — appalled by events” and “desperately taxed.” Eden speculated privately that Churchill had had a stroke.

Churchill wrote Roosevelt that he was finding it very difficult to get over the fall of Singapore. It may have had as traumatic an impact on him as the Dardanelles did in the First World War. In his public speeches he continued to exude confidence but never withheld the realities of the situation. To the Conservative Party Council Meeting, he said: “This is a very hard war. Its numerous and fearful problems reach down to the very foundations of human society. Its scope is worldwide, and it involves all nations and every man, woman, and child in them. Strategy and economics are interwoven. Sea, land, and air are but a single service. The latest refinements of science are linked with the cruelties of the Stone Age. The workshop and the fighting line are one. All may fall, and all will stand together. We must aid each other, must stand by each other.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.