1940-1942

Spring 1942 (Age 67)

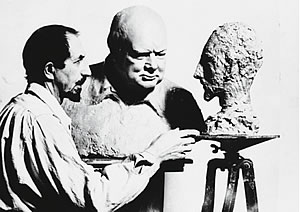

Winston Churchill, Parliament Square, London © Sue Lowry & Magellan PR

March 12, 2015

Trouble in North Africa and the Far East

Harry Hopkins and General Marshall visited Churchill to relay President Roosevelt’s “heart and mind” concerning a second front. They told the Prime Minister that American public opinion was weighted toward priority against Japan, but that American leaders considered Germany the primary enemy. They agreed on a cross-channel invasion in 1943 and named it Operation Roundup. In the meantime, they would engage the enemy in Africa and, Churchill hoped, Norway. The Germans prepared for the cross-channel assault by appointing Field Marshal Von Rundstedt Commander in Chief, Atlantic Wall Defences.

Losing patience with the pace of war in North Africa, Churchill ordered General Auchinleck to engage the enemy, but Rommel was the first to take the initiative with an attack on 26 May. Churchill pressed the importance of not losing Malta as a supply base, and sent the following message to Auchinleck: “Your decision to fight it out to the end is most cordially endorsed. We shall sustain you whatever the result. Retreat would be fatal. This is a business not only of armour but of willpower.”

While the battles raged in Africa there was also considerable action elsewhere. Bataan and Corregidor fell but the Japanese Navy was stopped at the Battle of Midway. In Europe the Allies sent 1,000 bombers against Cologne. Germany lost a potential successor to Hitler with the assassination of Heydrich. As the Germans waged campaigns against partisans throughout the Eastern Front, news reached Warsaw that gas was being used on Jews in Auschwitz.

Churchill decided that plans for operations had to be finalized so he set out to visit Roosevelt in America. Before leaving he advised the King to appoint Anthony Eden as Prime Minister should anything happen on this trip. The British and American leaders met first at Roosevelt’s home at Hyde Park, New York. On returning to Washington, Churchill was informed that Tobruk had fallen. This was one of the heaviest blows he received during the war, comparable to the loss of Singapore.

Before returning to Britain, he wrote Auchinleck: “Do not have the slightest anxiety about the course of affairs at home. Whatever views I may have about how the battle was fought or whether it should have been fought a good deal earlier, you have my entire confidence and I share your responsibilities to the full …”

The course of affairs at home, which Churchill called “a beautiful row,” involved a debate on a vote of censure in the House of Commons. Churchill later wrote that had he led a party government he might have suffered the fate of Chamberlain in May 1940, but the National Coalition Government was strong enough to survive “a long succession of misfortune and defeats in Malaya, Singapore and Burma; Auchinleck’s lost battle in the Desert, Tobruk, unexplained, and, it seemed, inexplicable; the rapid retreat of the Desert Army and the loss of all our conquests in Libya and Cyrenaica; four hundred miles of retrogression towards the Egyptian frontier. . .

In this case Churchill’s Government was supported by 475 votes to 25. Parallels were drawn between Churchill and Pitt who experienced similar dark days in 1799, but, sustained by the House of Commons, emerged victorious.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.