1940-1942

Autumn 1941 (Age 67)

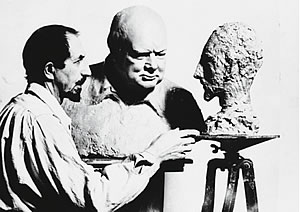

Winston Churchill, Parliament Square, London © Sue Lowry & Magellan PR

March 12, 2015

The Empire of Japan attacks the American Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor

The war raged on the Eastern Front as the Germans began their offensive towards the Don River and the Red Army counterattacked in the Ukraine and at Leningrad. The German hold on France tightened as pre-war leaders Daladier, Reynaud and Blum were arrested by Petain. Although Churchill had regular meetings with King George VI, on 28 October His Majesty and the Queen bestowed a signal honour on the Prime Minister by coming to lunch with him at No. 10 Downing Street.

Churchill knew that he was going to have to change the command structure of the military if he was going to win the war, and that changes must start at the top with the replacement of Sir John Dill as Chief of the Imperial General Staff. He selected General Sir Alan Brooke because of “Brookie‘s” “combination of wisdom and vigour which I have found refreshing.” Sir John Dill was appointed Governor of Bombay and later went to the United States as Head of the British Joint Staff Mission.

Churchill enjoyed “the sleep of the saved and thankful.”

Events began to focus Churchill’s attention on the Far East. In October, Tojo became Premier of Japan. In early December, Canada was asked to send forces to Hong Kong and the battleships HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales were sent to Singapore. On the evening of 7 December Churchill was at Chequers with Averell Harriman and American Ambassador Winant when the radio announced “something about the Japanese attacking the Americans.” According to Winant, Churchill jumped to his feet, announcing “we shall declare war on Japan.” Winant replied: “Good God, you can’t declare war on a radio announcement.” Churchill immediately telephoned Roosevelt and assured him that Britain’s declaration of war would follow close behind that of the United States.

That night, confident that with the United States now in the war victory was inevitable, Churchill enjoyed “the sleep of the saved and thankful.”

Within days of sending Anthony Eden to Russia, Churchill boarded HMS Duke of York for America. He wanted to encourage Russia’s resistance to the Germans so no pressure was brought upon them to declare war against Japan. Eden thought that Russian support could be ensured by recognizing its western border, established by the nefarious agreement with Hitler. Churchill adamantly opposed any deal concerning these borders. To Eden he telegraphed: “We have never recognized the 1941 frontiers of Russia except de facto. They were acquired by acts of aggression in shameful collusion with Hitler. The transfer of the peoples of the Baltic states to Soviet Russia against their will would be contrary to all the principles for which we are fighting this war and would dishonour our cause.” Recognition of the subjugation of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania would, in Churchill’s view, be a violation of the Atlantic Charter.

Roosevelt had suggested a meeting for mid-January but Churchill was anxious to meet quickly in order to establish at least two priorities: the importance of the naval situation and primacy of Europe in the American war effort. The meetings of the British and American military and political leaders established the defeat of Germany as the key to victory in the war.

On Christmas Eve, from the balcony of the White House, Churchill talked of feeling at home while so far from his native land:

“Whether it be the ties of blood on my mother’s side, or the friendships I have developed here over many years of active life, or the commanding sentiment of comradeship in the common cause of great peoples who speak the same language, who kneel at the same altars, and, to a very large extent, pursue the same ideals, I cannot feel myself a stranger here..

The day after Christmas he told a joint meeting of the Senate and the House of Representatives: “I cannot help reflecting that if my father had been American and my mother British, instead of the other way round, I might have got here on my own.”

Later that evening, Churchill probably suffered what his doctor, Sir Charles Wilson, diagnosed as coronary insufficiency, otherwise known as angina pectoris. Knowledge of this attack remained between doctor and patient only. His health did not prevent him from travelling by train to Ottawa where he addressed the Canadian Parliament. Expressing confidence in the British Empire’s ability to prevail he declared: “We have not journeyed all this way across the centuries, across the oceans, across the mountains, across the prairies, because we are made of sugar candy.”

Reviewing the war, he said that when he had told the French that whatever they did, Britain would continue to fight on alone, the French generals had commented that in three weeks Britain would have “her neck wrung like a chicken.” He then uttered one of his most famous and defiant remarks of the war: “Some Chicken! [pause] Some Neck!” The Canadian Parliamentarians roared and applauded. They had just seen all the characteristics which had brought Britain this far. The road ahead would be long and hard, but victory was now surely inevitable.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.