Reference

The Complete Poems of Sir Winston Churchill

October 17, 2008

Compiled and annotated by Douglas J. Hall

In declaring Winston Churchill an Honorary Citizen of the United States, President Kennedy said (quoting Ed Murrow), “He mobilized the English language and sent it into battle.” The President was referring in particular to 1940, but Churchill’s stimulating use of his native language was constant throughout his long and distinguished life. Language has two forms, written and spoken. Churchill was a master of both. As a journalist, essayist, author, novelist, historian, biographer, editor, correspondent, communicator, conversationalist and speaker he had few equals in any one of those fields, much less all of them. He has been described as a law unto himself in his use of words, as in so many other matters.

In 1906, Churchill addressed the annual dinner of the Authors’ Club:

Authors are the happy people in the world, whose work is pleasure. No one can set himself to the writing of a page of English composition without feeling a real pleasure in the medium in which he works, the flexibility and the profoundness of his noble mother tongue. The House of Commons may do what it likes, and so may the House of Lords; the American market may have its bottom knocked out, the heathen may rage in every part of the globe; Consuls may fall, and the suffragists rise, but the author is secure as almost no other man is secure. I have sometimes fortified myself amid the vexations, vicissitudes and uncertainties of political life by the reflection that I might find a secure line of retreat on the pleasant, peaceful and fertile country of the pen, where one need never be idle or dull.

Those spoken words, as written words, read just as well as they must have sounded to that gathering over ninety years ago.

Churchill spoke and wrote with a rhythm which made it almost poetical. He arranged his notes for his speeches in a format closely resembling blank verse. Although he was never a prolific poet himself he greatly enjoyed poetry and had a remarkable capacity to commit to memory copious lines of verse which he loved to recall and recite at appropriate moments. In his writings and speeches he regularly quoted lines from Macaulay and was still able to recite long passages from memory well into extreme old age.

Winston Churchill was truly a poet at heart. A little book was published years ago with a similar title to this article, but contained nothing by him. This little collection, compiled with the help of his daughter, presents the poems he is known to have composed himself. They are taken from Churchill Canto, a larger work by this writer, as yet unpublished, containing a selection of verse with which Churchill was in some way associated.

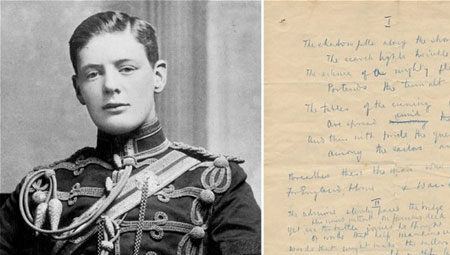

“The Influenza” was written by the fifteen-year-old Churchill in 1890 when he was a pupil at Harrow School. For his effort he received a House Prize which went some way towards redeeming his position, both with his schoolmasters and his parents who had been less than impressed by his recent behaviour and scholastic achievement. The poem is remarkably accomplished for a fifteen-year-old and gives an early glimpse of Churchill’s command of language, his sense of history and his impish humour. It was published in The Harrovian, the Harrow School magazine, fifty years later on 10 December 1940, when the “Famous Old Harrovian” had become quite a celebrity. See Winston Churchill and Harrow by E. D. W Chaplin (Harrow School Bookshop, 1941).

Oh how shall I its deeds recount

Or measure the untold amount

Of ills that it has done?

From China’s bright celestial land

E’en to Arabia’s thirsty sand

It journeyed with the sun.

O’er miles of bleak Siberia’s plains

Where Russian exiles toil in chains

It moved with noiseless tread;

And as it slowly glided by

There followed it across the sky

The spirits of the dead.

The Ural peaks by it were scaled

And every bar and barrier failed

To turn it from its way;

Slowly and surely on it came,

Heralded by its awful fame,

Increasing day by day.

On Moscow’s fair and famous town

Where fell the first Napoleon’s crown

It made a direful swoop;

The rich, the poor, the high, the low

Alike the various symptoms know,

Alike before it droop.

Nor adverse winds, nor floods of rain

Might stay the thrice-accursed bane;

And with unsparing hand,

Impartial, cruel and severe

It travelled on allied with fear

And smote the fatherland.

Fair Alsace and forlorn Lorraine,

The cause of bitterness and pain

In many a Gaelic breast,

Receive the vile, insatiate scourge,

And from their towns with it emerge

And never stay nor rest.

And now Europa groans aloud,

And ‘neath the heavy thunder-cloud

Hushed is both song and dance;

The germs of illness wend their way

To westward each succeeding day

And enter merry France.

Fair land of Gaul, thy patriots brave

Who fear not death and scorn the grave

Cannot this foe oppose,

Whose loathsome hand and cruel sting,

Whose poisonous breath and blighted wing

Full well thy cities know.

In Calais port the illness stays,

As did the French in former days,

To threaten Freedom’s isle;

But now no Nelson could o’erthrow

This cruel, unconquerable foe,

Nor save us from its guile.

Yet Father Neptune strove right well

To moderate this plague of Hell,

And thwart it in its course;

And though it passed the streak of brine

And penetrated this thin line,

It came with broken force.

For though it ravaged far and wide

Both village, town and countryside,

Its power to kill was o’er;

And with the favouring winds of Spring

(Blest is the time of which I sing)

It left our native shore.

God shield our Empire from the might

Of war or famine, plague or blight

And all the power of Hell,

And keep it ever in the hands

Of those who fought ‘gainst other lands,

Who fought and conquered well.

Churchill’s term of endearment for his wife, Clementine, was Pussy Cat. He often embellished his letters to her with small drawings of cats. In April 1924 Winston, assisted by the children, moved into Chartwell. These lines were in a letter to Clementine who was in Dieppe. See Mary Soames, Speaking for Themselves: The Personal Letters of Winston and Clementine Churchill (1998).

Only one thing lacks these banks of green—

The Pussy Cat who is their Queen….

As a child Mary Churchill had a pet pug called “Punch.” One day Punch became desperately ill. Mary and her sister Sarah were disconsolate. Their father composed this ditty to comfort them and all three sang it together to the ailing dog. Lady Soames adds that the treatment worked! Published by permission of Lady Soames from Sarah Churchill, A Thread in the Tapestry (London: 1967).

Oh, what is the matter with poor Puggy-wug

Pet him and kiss him and give him a hug.

Run and fetch him a suitable drug,

Wrap him up tenderly all in a rug,

That is the way to cure Puggy-wug.

Walter Graebner, Churchill’s Life editor, writing in My Dear Mr. Churchill (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965) related how, after dinner at Chartwell one evening he and his wife were discussing the use of sleeping pills with Winston and Clementine. Churchill, with an impish grin, addressed Mrs. Graebner with this impromptu piece of doggerel. Not great poetry, but the kind of thing Churchill was very good at — and which pleased him hugely.

Your husband is a very temperate man -hmph

He needs – er – a little sedative to sleep.

He should drink all the brandy that he can -hmph

You’ve really very little cause to weep.

In Painting as a Pastime (London:Odhams 1948) Churchill used the rare, possibly unique, combination of French and verse to explain his preference for painting in oils rather than water-colours.

La peinture á l’huile

Est bien difficile,

Mais c’est beaucoup plus beau

Que la peinture á l’eau.

Anthony Montague Browne, Churchill’s Private Secretary 1952-65, quotes this example of WSC’s impromptu verse in Long Sunset (London: Cassell 1995, reprinted by kind permission). Mr. Montague Browne believes that this “schoolboy” verse may have been Churchill’s own composition. Such “high poetic flights,” he says, did not reflect enmity or contempt, but did not reflect much high esteem either!

The Czechoslovaks

Lie flat on their backs

Emitting loud quacks

The Yugoslovaks

All die of the pox.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.