Reference

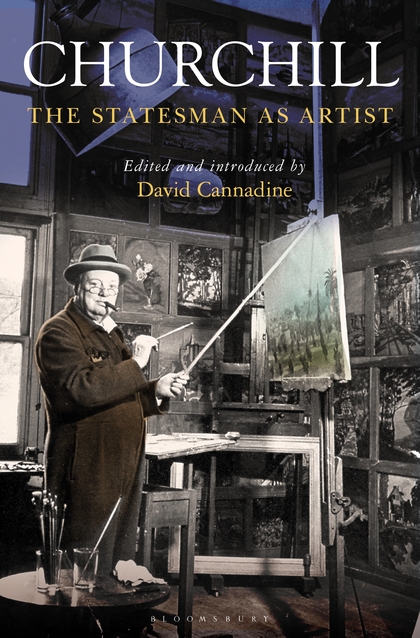

Churchill: The Statesman as Artist

September 5, 2018

Extract taken from Churchill: The Statesman as Artist published by Bloomsbury Continuum.

To get 30% off through Bloomsbury.com, add the code ARTIST30 to the checkout.

Churchill did not begin painting until his fortieth year, but his family background and his own talents and temperament provide many clues and pointers as to how and why he made a success of it when he eventually did pick up a paintbrush. Yet as with many aspects of his life and career, Churchill’s artistic endeavours need to be set and understood in a broader context. As a soldier in India, he had devoted his leisure hours to playing polo and to reading as many learned books as he could get his hands on. Had he been less focused on horses and belated self- improvement, he might equally have taken up painting, because this was something that many soldiers did. As Churchill had already discovered at Sandhurst, learning to draw, and to appreciate terrain and topography from a military point of view, were essential parts of an officer’s training, while the long days of leisure, often spent in unfamiliar and picturesque imperial locations, encouraged many soldiers to take up their sketchbooks or paintbrushes to help while away the time. One such soldier- artist had been the American general and president Ulysses S. Grant, who began painting while a cadet at West Point during the early 1840s; another was General Lord Rawlinson, with whom Churchill would go on a canvas- covering holiday in France in March 1920. During the Second World War, several high- ranking military men on the Allied side were painters, including Generals Eisenhower, Auchinleck and Alexander (and Eisenhower would complete a portrait of Churchill, from photographs, during his presidency). As a soldier- turned- artist, Churchill was neither unusual nor unique: but he was a better artist, and became more famous than any of his contemporary practitioners.

Just as many soldiers painted, so many depressives sought solace in creativity. Writers who battled with despair have included Edgar Allen Poe, John Keats, Charles Dickens and Ernest Hemingway, while Charles Darwin and Tchaikovsky were similarly afflicted. Many artists were blighted by melancholy temperaments, among them Michelangelo, Van Gogh, Gauguin and Jackson Pollock. Among earlier statesmen, the father of Frederick the Great, King Frederick William I of Prussia, took up painting as an antidote to depression, and so, in more recent times, has President George W. Bush, as a way of coming to terms with his responsibility for the casualties in the Iraq War. In Churchill’s case, ‘inborn melancholia’ was a hereditary condition in the Marlborough family with which at least five dukes were afflicted, and early in his time in the House of Commons, he learned that something he called the ‘black dog’ would never be far away. One of the reasons Churchill worked so hard for so much of his life, and developed so many hobbies and additional ways of keeping busy, was because constant activity during his waking hours seemed the best means to hold the misery and despair brought on by the ‘black dog’ at bay. And when, in enfeebled old age, he was no longer able to summon up the energy to stay active, he seems to have descended into a sad twilight of almost perpetual gloom. But from the late 1910s to the late 1950s, painting was one of the most successful stratagems that Churchill devised for banishing depression. And as is well known, it was during the darkest time of his political life, when the ‘black dog’ tormented him as never before, that he first took up his brushes.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.