For Educators

Institute Rationale

October 28, 2009

Churchill is best known for his leadership of Great Britain during the Second World War. “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat,” he told the House of Commons in May 1940. His words of gratitude to British airmen still reverberate: “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” But his influence extends far beyond the war itself. His life and long political career spanned the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and one is hard pressed to name a significant political event in the West during his adult life in which he did not play a significant part or upon which he did not make influential comment. Churchill left us a copious record of political achievement, but he also reflected on the human condition, which means that he can be studied as a means of approaching the most important political questions. Particularly, Churchill confronted, and wrote and reflected upon, three of the twentieth century’s most resonating political questions–questions which deeply involved Americans: the dangers of Nazi and communist tyranny, the “Grand Alliance” of World War II, and the advent of the Cold War.

is best known for his leadership of Great Britain during the Second World War. “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat,” he told the House of Commons in May 1940. His words of gratitude to British airmen still reverberate: “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” But his influence extends far beyond the war itself. His life and long political career spanned the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and one is hard pressed to name a significant political event in the West during his adult life in which he did not play a significant part or upon which he did not make influential comment. Churchill left us a copious record of political achievement, but he also reflected on the human condition, which means that he can be studied as a means of approaching the most important political questions. Particularly, Churchill confronted, and wrote and reflected upon, three of the twentieth century’s most resonating political questions–questions which deeply involved Americans: the dangers of Nazi and communist tyranny, the “Grand Alliance” of World War II, and the advent of the Cold War.

One of the most decisive changes in the world in which Churchill lived was the emergence of the United States as a major power. Churchill’s relationship with his mother’s homeland spans his entire life, from his schoolboy fascination with Buffalo Bill to his honorary American citizenship in 1963. Churchill had working relationships with three presidents during his more than sixty years in politics; together they tackled the most difficult issues of international relations. Churchill’s understanding and appreciation of FDR’s commanding presence and statesmanship is especially to be noted. Although they did not agree on everything important, their collaboration during the great crises of the war is an especially significant story.

Yet Churchill’s relationship with America was not merely one of practical convenience or necessity. He viewed the two nations as being linked by principle. He viewed the United States and Britain as very closely related politically-indeed, as essentially the same. He expressed this idea when speaking to a joint session of Congress as the United States  entered the war. Churchill joked that it was only an accident of birth that had placed him in the legislative assembly across the Atlantic rather than in Washington, D.C. Often he made references to Anglo-American action which incorporated the political and legal documents of the two nations and emphasized the common traditions and goals of the two peoples. He was opposed to tyranny in any form, and at the core of his identity as a statesman was his unceasing call to the world to order itself according to the political principles of freedom, especially those which are the legacies of the Anglo-American political tradition.

entered the war. Churchill joked that it was only an accident of birth that had placed him in the legislative assembly across the Atlantic rather than in Washington, D.C. Often he made references to Anglo-American action which incorporated the political and legal documents of the two nations and emphasized the common traditions and goals of the two peoples. He was opposed to tyranny in any form, and at the core of his identity as a statesman was his unceasing call to the world to order itself according to the political principles of freedom, especially those which are the legacies of the Anglo-American political tradition.

And yet Churchill noted important differences between the political regimes of the American republic and British constitutional monarchy. Churchill had less than a positive opinion about the United States Supreme Court, for example. His biographer Martin Gilbert wrote that Churchill proclaimed his first act if elected president of the United States would be to select all his Cabinet Secretaries from among recently elected representatives and senators. Teachers of American history and government will be able to explore a new perspective on our political arrangements.

Churchill’s statesmanship spanned more than half of the twentieth century, from the great Liberal reforms of Edwardian Britain and the arrival of mass democracy, through two world wars, the Depression, and the formation of the United Nations, to the advent of the Cold War. He was the only individual to occupy high office in both world wars. His political prominence lasted four times longer than Franklin Roosevelt’s and at least twice as long as that of any other major figure. His relationship with America was equally enduring. Churchill visited America sixteen times, his first visit in 1895 and his last in 1961. Churchill’s era marked the decline of British imperialism and the emergence of the United States as a world power, with world responsibilities. After World War II, Churchill realized that the fate of the free world rested largely with the new superpower that had emerged across the Atlantic and confided to President Truman that if he were to be born again, he would wish to be an American. The greatest contribution Churchill can make to American teachers and students today is his optimism for what he called “the Great Republic,” knowing that whatever mistakes Americans made, there has never been a more noble and altruistic world power.

|

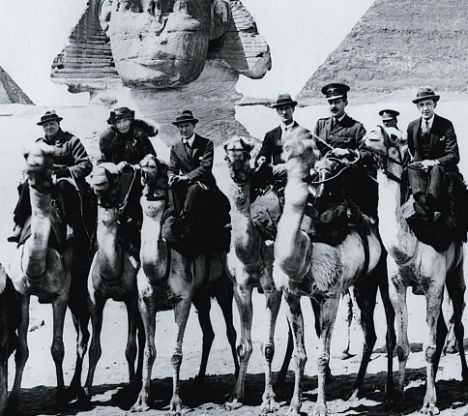

| Left to right, Churchill, Gertrude Bell, and T. E. Lawrence in Egypt for Cairo Conference, 1921 |

With remarkable prescience, Winston Churchill foresaw both world wars and in time predicted their outcomes. He envisioned the perils of the nuclear age in his essay “Shall We All Commit Suicide?” in 1924, ten years before Einstein sent his famous letter to Roosevelt warning of the implications of splitting the atom. Drawing up the boundaries of the modern Middle East in 1921, Churchill saw the dangers of ethnic division in Iraq; he argued for a Kurdish homeland there, and urged a settlement between Arabs and Jews in Palestine before attitudes hardened and lines were drawn. Churchill recognized the Hitler menace before any other world leader. He was first to proclaim the threat of Soviet tyranny in his 1946 “Iron Curtain” speech, yet also first to argue for a “meeting at the summit” among leaders of Russia and the West.

Churchill’s vision, nurtured by his educated and vivid imagination, was notable in two fields to which he was devoted, science and history. His scientific imagination, fueled in part by his relationship with Oxford professor Charles Lindemann (later Lord Cherwell), led to the establishment of Churchill College, Cambridge, a center for the study of science and the home of our Institute for the first two weeks. As Churchill Centre academic adviser Professor Paul Alkon has written, “Imaginative engagement with science was one of Churchill’s fundamental traits. It is perhaps the feature of his mind and writing that best allows us to understand his remarkable flexibility in dealing with the staggering changes that he confronted in moving to the atomic age from his origins as a Victorian cavalry officer who rode in the charge of the 21st Lancers at the Battle of Omdurman in 1898….”

In his famous wartime essay, Isaiah Berlin wrote of Churchill that “the single, organizing principle of his moral and intellectual universe, is an historical imagination so strong, so comprehensive, as to encase the whole of the present and the whole of the future in a framework of a rich and multi-colored past.” As Churchill remarked, “The only thing that’s new in the world is the history that you don’t know.” Thus he admonished, “Study history! Study history.”

Churchill is also remarkable for his moral example. He not only fought for humane values but also exemplified them as a powerful writer, orator, and historian, and as a statesman of rare magnanimity. Alone among the victorious Allied leaders in 1918, he urged that ships full of food be sent immediately to blockaded Germany; and after World War II he said, “my hate for the Germans died with their surrender.”

Churchill’s political philosophy ran deep and still resonates when we address the twenty-first century’s most vexatious questions. Or are these questions so very new? He was, as his biographer wrote, “first and foremost a parliamentarian, a supporter, practitioner, and upholder of parliamentary democracy.” His relationship with America was not merely one of practical convenience or necessity. He viewed the two nations as linked by political principles. Addressing a joint session of Congress as the United States entered World War II, Churchill joked that it was only an accident of birth that had placed him in the legislative assembly across the Atlantic rather than in Washington, D.C. A close examination of British politics and Churchill’s participation in it are important parts of the Institute.

This Institute offers a three-pronged approach to examining the Anglo-American relationship through the life, reflections, and experiences of Winston Churchill: lectures, discussions, and participants’ personal responses to the readings and films; projects by teachers using primary documents from the Churchill Archives Centre at Churchill College, Cambridge; and visits to major Churchill sites in Britain.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.