For Educators

For Educators

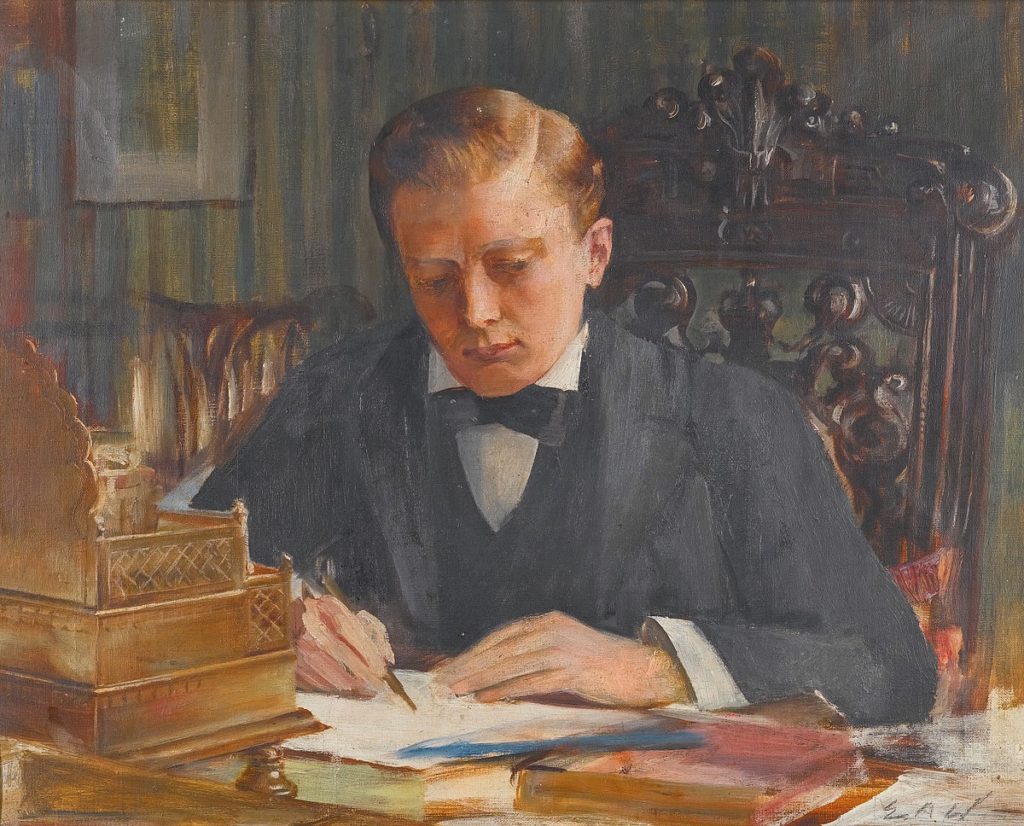

Churchill as a young man, by Edwin Arthur Ward

August 24, 2021

Perhaps there is no greater theme upon which to reflect during one’s study of Winston Churchill than “Education,” for it begins to address the endlessly fascinating question of how Churchill came to be Churchill. To probe the dissimilarities between formal education and self-education is to inquire into the heart of the matter. We commend to you Churchill’s autobiography My Early Life which he wrote in 1930, looking back in middle age on his first thirty years of life. Its charm is illustrated in the excerpt below:

‘It was at ‘The Little Lodge’ I was first menaced with Education. The approach of a sinister figure described as ‘the Governess’ was announced. Her arrival was fixed for a certain day. In order to prepare for this day Mrs. Everest [his nurse] produced a book called Reading without Tears. It certainly did not justify its title in my case. I was made aware that before the Governess arrived I must be able to read without tears. We toiled each day. My nurse pointed with a pen at the different letters. I thought it all very tiresome.

Our preparations were by no means completed when the fateful hour struck and the Governess was due to arrive. I did what so many oppressed peoples have done in similar circumstances: I took to the woods. I hid in the extensive shrubberies – forests they seemed – which surrounded ‘The Little Lodge.’ Hours passed before I was retrieved and handed over to ‘the Governess.’ We continued to toil every day, not only at letters but at words, and also at what was much worse, figures. Letters after all had only got to be known, and when they stood together in a certain way one recognised their formation and that it meant a certain sound or word which one uttered when pressed sufficiently. But the figures were tied into all sorts of tangles and did things to one another which it was extremely difficult to forecast with complete accuracy. You had to say what they did each time they were tied up together, and the Governess apparently attached enormous importance to the answer being exact. If it was not right, it was wrong. It was not any use being ‘nearly right.’ In some cases these figures got into debt with one another: you had to borrow one or carry one, and afterwards you had to pay back the one you had borrowed.

These complications cast a steadily gathering shadow over my daily life. They took one away from all the interesting things one wanted to do in the nursery or in the garden. They made increasing inroads upon one’s leisure. One could hardly get time to do any of the things one wanted to do. They became a general worry and preoccupation. More especially was this true when we descended into a dismal bog called ‘sums.’ There appeared to be no limit to these. When one sum was done, there was always another. Just as soon as I managed to tackle a particular class of these afflictions, some other much more variegated type was thrust upon me. My mother took no part in these impositions, but she gave me to understand that she approved of them and she sided with the Governess almost always.’

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.