Finest Hour 199

“Wise Counsel and Also Friendship”

Queen Elizabeth II and Winston Churchill

March 27, 2024

Winston Churchill and HM Queen Elizabeth II

Finest Hour 199, Special Issue 2022

Page 08

By Winston Churchill and HM Queen Elizabeth II

Hugo Vickers’ books include Elizabeth, The Queen Mother (Hutchinson, 2005).

Sir Winston Churchill was the Queen’s first Prime Minister. He was the first person she met as she descended the steps of the Argonaut Airliner Atalanta after a flight of more than nineteen hours from Kenya in 1952, following the death of her father at Sandringham. The relationship between the new, young Sovereign and the elderly Prime Minister developed from his apprehension at her youth and inexperience to genuine and deep love on his part. On her part, the Queen had enormous respect for the former wartime leader and profound gratitude for his wisdom and guidance.

Churchill’s doctor, Lord Moran, wrote that for Winston the history of England was embedded in the Royal House. Moran quoted several comments by his famous patient. Looking at a photograph of the Queen, dressed in white with long white gloves and a radiant smile in February 1953, Churchill said: “Lovely…She’s a pet. I fear they may ask her to do too much. She’s doing so well.”¹ A month later, Churchill added: “Lovely, inspiring. All the film people in the world, if they had scoured the globe, could not have found anyone so suited to the part.”² And in October 1954, Churchill looked at photographs of the Queen meeting Italian film stars and judged, “She knocks ’em all endways. Lovely she is.”³

Churchill had lost the postwar election in 1945, but had once more become King George VI’s Prime Minister in October 1951, to the King’s delight, when His Majesty was recovering from a serious operation and in failing health. The King died on 6 February 1952, and the news was given to the Prime Minister in person by Sir Edward Ford, one of the King’s private secretaries then in London, who had received the coded message: “Hyde Park Corner.” Jock Colville, Churchill’s private secretary, saw him soon afterwards and tried to cheer him up by saying how well he would get on with the new Queen, “but all he could say was that he did not know her and that she was only a child.”⁴ In the House of Commons, Churchill took a more robust approach:

2025 International Churchill Conference

A fair and youthful figure, Princess, wife and mother is the heir to all our traditions and glories never greater than in her father’s days, and to all our perplexities and dangers never greater in peacetime than now. She is also heir to all our united strength and loyalty.

She comes to the Throne at a time when a tormented mankind stands uncertainly poised between world catastrophe and a golden age. That it should be a golden age of art and letters, we can only hope—science and machinery have their other tales to tell—but it is certain that if a true and lasting peace can be achieved, and if the nations will only let each other alone, an immense and undreamed of prosperity with culture and leisure ever more widely spread can come, perhaps even easily and swiftly, to the masses of the people in every land.

Let us hope and pray that the accession to our ancient Throne of Queen Elizabeth the Second may be the signal for such a brightening salvation of the human scene.⁵

These were to prove prophetic words as seventy glorious years did indeed stretch before the British people, something that was greatly remarked on following the Queen’s death on 8 September 2022. Churchill may have had a momentary lapse of memory in suggesting he did not know the Queen. And if that is what he really thought, the situation was soon going to change.

First Encounters

In fact, Churchill had first set eyes on the young Queen at Balmoral in 1928. Besides King George V, Queen Mary, and the Household, the only other figure there was “Queen Elizabeth—aged 2.” “The last is a character,” wrote Churchill to his wife, deliberately exaggerating the title of the young princess to emphasize the qualities that he discerned in her. “She has an air of authority and reflectiveness astonishing in an infant.”⁶ Churchill may also have observed the Princess at royal garden parties in 1931 and 1935. They were certainly both present at the same time. By 1937 he had realised that, with her mother’s blood, two royal houses were united. This excited him:

In the heir presumptive to the Crown, the Princess Elizabeth, the Houses of Stuart & Hanover both find a representative of their blood, cheering even to the White Rose League, and reconciling in the fullness of time one of the most prolonged & poignant quarrels of British history.⁷

Churchill sent the Princess roses on her fifteenth birthday in April 1941, and she sent him a thoughtful and encouraging letter of thanks: “I am afraid you have been having a very worrying time lately, but I am sure things will begin to look up again soon.”⁸

It was not long before Churchill was considering how best he could help prepare the heir to the throne for her eventual role as Queen. In June 1943 he recommended to Lord Simon, the Lord Chancellor, that since she was soon to be eighteen, she should be appointed a member of the Council of State, so that she “should have every opportunity of acquiring experience in affairs.”⁹ This resulted in the Prime Minister going to the bar of the House of Commons to present a message from the King requesting an amendment to the Regency Act of 1937 so that Princess Elizabeth could become a Counsellor of State. This was arranged, and Princess Elizabeth first acted as such in July 1944, when the King visited the Italian battlefields soon after her eighteenth birthday. But an idea mooted by the Cabinet that Princess Elizabeth should be created Princess of Wales, which rather appealed to Churchill, was vetoed by the King, who understood these things better than his ministers. That would not have been appropriate.

Over the years Churchill heard news of the Princess, and he must have seen her from time to time when he went to see the King and Queen during the Second World War, though those meetings took place largely in Buckingham Palace, while the princesses were living mainly in Windsor Castle. In January 1944 Churchill’s close friend Lady Violet Bonham Carter wrote to him that her son Mark, who had lately escaped from a prisoner of war camp in Italy, had been summoned to Windsor by the Princess, who was Colonel of his regiment—the Grenadier Guards—to tell her of his experiences. This morphed into a dinner and dance with champagne and music.

On 21 April 1944 Princess Elizabeth reached her eighteenth birthday. And how did Churchill celebrate this? He sent her a copy of his biography of the first Duke of Marlborough. Politely she thanked him: “There is nothing I would rather have than your Life of Marlborough, and I thank you most warmly for giving it to me.”10 (See story p. 29.) In November of the same year, consistent with his wish to prepare her as a future constitutional monarch, Churchill sent the Princess a copy of the King’s speech that was to be delivered in Parliament the next day. He told her that this was a tradition that had been established in the reign of Queen Victoria. In all these things Churchill was aware of the role Princess Elizabeth would one day play without realising that it would come so soon and that it would be his duty to steer the young Queen through the early years of her reign just as an earlier Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, had done for Queen Victoria.

At the time of Princess Elizabeth’s wedding to Prince Philip in 1947, Churchill praised the bride for her “unerring graciousness and understanding and the same human simplicity which has endeared the Royal House to the people of this country” and predicted that millions would welcome the wedding as a flash of colour on the hard road the country was then travelling.

Four years later, about ten weeks before the King died, Richard Casey, then Australian Minister for External Affairs, lunched with the heir to the throne. He afterwards told Churchill that he found the Princess so serious that he felt she had been warned or had some instinctive knowledge that she would soon be called upon to serve. Churchill replied: “Yes, there is too much care on that young brow.”11 All too soon this proved correct.

The New Queen

Churchill, by then one of the most senior members of the Privy Council, was present at the Accession Council at St. James’s Palace and afterwards watched the Queen’s proclamation from a window in Friary Court. Naturally, the Prime Minister attended the King’s funeral, and he went for his first official audience of the new Queen at Clarence House on 12 February.

That idiotic television series The Crown muddled the professional relationship between Churchill and his Queen, even causing the actress playing her to bestow a kiss on him when he was about to die in 1965. No, that is one of many things that never happened. I hope readers of Finest Hour are aware of how important it is to ignore the misconceptions of that television series. The truth is more interesting.

Various issues arose in those early years, and the young Queen naturally deferred to her distinguished Prime Minister. One of the first concerned the name of the Royal House. Customarily, when a Queen regnant marries, so the name of the Royal House changes, taking the name of the husband. Thus Queen Victoria was the last of the House of Hanover, which became SaxeCoburg-Gotha when she married Prince Albert. During the First World War, however, anti-German sentiment in Britain inspired Queen Elizabeth II’s grandfather, King George V, to adopt the name Windsor in place of the German name inherited from his grandfather.

Soon after the funeral of George VI, Lord Mountbatten, uncle to Prince Philip, boasted over a dinner at Broadlands, not without reason, that the House of Mountbatten now reigned over the land. Prince Ernst August of Hanover was at the table and subsequently reported the remark to Queen Mary, widow of George V. The dowager Queen had a sleepless night over the issue. Soon after, it was decided that the House of Windsor should continue as more appropriate.

Prince Philip wrote a well-crafted protest about this calling for the new House to take the name of Edinburgh, which would have worked no better than Mountbatten. Churchill was annoyed by this and more so by Mountbatten’s “tactless assertion.”12 The Prime Minister swung it on the young Queen that her grandfather wished it to be the House of Windsor, and that settled the matter.

Nor did Churchill like the idea of the Queen and Prince Philip remaining at Clarence House, which they greatly preferred to do. Churchill insisted that the Sovereign had to live in the Sovereign’s official residence. And so it came about that the young Queen took up residence in Buckingham Palace, much of which is taken up by offices and rooms of state.

There is no suggestion that the Queen felt any resentment to these strictures. Brought up with constitutional training, she knew her role was to take advice. Colville found her “at ease and self-possessed” when he dined with her that April.13 Churchill enjoyed his weekly meetings with the new Queen, and the two were soon talking about many things, not least about a shared interest in racing. Her first private secretary, Sir Alan Lascelles, wrote of her: “Her serenity was constant, her wisdom faultless. On the whole I consider her the most remarkable woman I have ever met.” Churchill shared Lascelles’ view of the young Queen:

Her immediate grasp of the routine business of kingship was remarkable. She never seemed to need an explanation on any point. Time after time I would submit to her papers on which several decisions were possible. She would look out of the window for half a minute and then say: “The second or third suggestion is the right decision”—and she was invariably right. She had an intuitive grasp of the problems of government and indeed of life generally, that I suppose had descended to her from Queen Victoria.14

In October 1952 Churchill went to stay with the Queen at Balmoral, having not seen her for two months. She was rather worried what to do with the old man because she had a party of her own generation staying. Aged seventy-eight, Churchill was disappointed not to have been asked to shoot, but he enjoyed talks with the Duke of Edinburgh and found the young Prince Charles developing well: “He is young to think so much.”15

Churchill also turned his mind to the future of the Queen Mother, who was only fifty-one when she became a widow. In April 1952 he had put forward an idea that she should be appointed Governor General of Australia (see page 27). During the Prime Minister’s Balmoral visit, Lady Jean Rankin, one of the Queen Mother’s redoubtable ladies-inwaiting, suggested he come over all by himself from the castle to Birkhall. This was an important visit, resulting in the widowed Queen Mother embracing a new life of service at a time when she might possibly have retreated permanently from public service.

New Honours

It was during a visit to Windsor Castle in April 1953 that the Queen offered Churchill the Garter. Her father had been disappointed that the Prime Minister had not accepted it at the end of the Second World War in 1945. Churchill had felt that it was the wrong time, though subsequently he worried that he had been discourteous. Originally he had preferred to remain plain Mr. Churchill, but he now justified the idea by recalling that the father of the first Duke of Marlborough had also been Sir Winston Churchill.

Furthermore, in 1946, the bestowal of the Order of the Garter had ceased to be on the recommendation of the Prime Minister, like most honours, but returned to being in the gift of the Sovereign. Churchill liked the romance of accepting it from the young Queen. He wrote to his early girlfriend Pamela Plowden, by then the widowed Countess of Lytton: “I took it because it was the Queen’s wish. I think she is splendid.”16

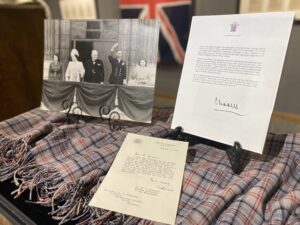

The Coronation took place on 2 June 1953. Sir Winston was a popular figure at this great ceremony for which he wore Garter robes, with the Garter star of Lord Castlereagh, loaned by the Marquess of Londonderry, and the famous George, owned by the first Duke of Wellington and generously loaned by the seventh Duke, even though he was himself a Knight of the Garter and might have liked to wear it. Three days later on 5 June, because Anthony Eden was unwell, Sir Winston presided over the Foreign Secretary’s banquet for the Queen at Lancaster House. On that occasion the Prime Minister wore the full dress uniform of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports.

New Challenges

Soon after the Coronation, Churchill suffered a stroke. This first became evident following a dinner on 23 June for the Italian Prime Minister, Alcide de Gasperi. Churchill found himself unable to move after dinner. The next day he presided at the Cabinet, but spoke with slurred speech and drooping mouth. He retreated to Chartwell, while his health, his recovery, and the timing of his possible retirement became the preoccupation of the Queen (and not only of the Queen, of course) until Churchill finally— eventually—stepped down in April 1955. At the beginning of August 1953 the Prime Minister visited the Queen at Royal Lodge, Windsor and told her that he would make the decision as to whether to retire or not depending on his ability to make the keynote speech at the Conservative Conference in October and to face Parliament.

During the Queen’s Commonwealth tour from October 1953 to May 1954, the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret served as Counsellors of State. Churchill paid two visits to the Queen Mother in the way that he would have had an audience of the Queen. These took place on 10 March and 4 May. The Queen Mother also received Anthony Eden, still Foreign Secretary, on 12 March.

In July 1954 there was a suggestion that the Queen might be persuaded to intervene in a serious dispute in the Cabinet. This concerned Churchill’s preoccupation to bring about a summit meeting between the leaders of Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union (then the only three nuclear powers), which he hoped would open the way to agreements about strategic arms reductions and thus avoid nuclear war. Churchill had lately visited Washington and been told that the United States did not warm to the idea but did not object to Britain having bi-lateral meetings with the USSR.

Churchill failed to see that, apart from American ambivalence, the Russians would never enter into such talks until the succession to Stalin had been settled, something that remained years away. Nevertheless, on his return to London, Churchill sent a telegram to Moscow proposing a meeting between himself and a senior Russian leader. This he announced to the Cabinet on 6 July, provoking Lord Salisbury, the Lord Privy Seal, to threaten to resign if the Prime Minister pursued this plan. Harry Crookshank, Leader of the House of Commons, did likewise. Most of the Cabinet supported the American stance, and most of them thought it was time for Churchill to retire.

Churchill felt strongly enough about his initiative that there was some fear he might threaten to resign himself if blocked by his Cabinet, knowing that this would create such an impossible situation it would force a General Election. In this impasse, Lord Swinton, the Commonwealth Secretary, and Lord Simmonds, the Lord Chancellor, both asked Colville independently to explain what was going on to Sir Michael Adeane, the Queen’s Private Secretary, with the idea that the Queen might need to intervene. They did so in the belief that it was in the Queen’s prerogative to caution her Prime Minister against precipitate action. As it happened, the Russians inadvertently resolved the problem for everyone by calling for multilateral meetings, which made Churchill’s original proposal redundant. From the point of view of historians, the potential involvement of the Queen remained untested.

On 31 March 1955 Churchill finally sent a private message to the Queen to say that he would resign on 5 April, thus ending a long cat and mouse game he had played with his successor, Anthony Eden. The evening before Churchill’s retirement, the Queen and Prince Philip dined at 10 Downing Street. There were about fifty guests, including senior cabinet ministers, figures such as the Duke and Duchess of Norfolk, and some key family friends of the Churchills. The next day Churchill put on his frock coat and top hat and made his way to Buckingham Palace for his farewell audience.

Colville had suggested to Adeane that the Queen offer Churchill a dukedom. This Colville had done, however, only after having carefully ascertained that Churchill would not accept it, the idea being that the outgoing Prime Minister would be given the distinctive honour of having declined to become a duke. The matter having been carefully arranged, Colville then panicked. He feared Churchill might change his mind, as he had done on so many previous occasions concerning his resignation. Colville recalled:

I was greatly disturbed because as I saw the Prime Minister going off in his frock coat and his top hat and knowing as I did that he was madly in love with the Queen—and this was clear from the fact that his audiences had been dragged out longer and longer as the months went by and very often took an hour and a half, at which I may say racing was not the only topic discussed, I was rather alarmed that sentimental feelings might indeed make him accept at the last moment.17

Fortunately Sir Winston told the Queen he would prefer to remain in the House of Commons for the rest of his life. He also thought that a dukedom might ruin the political careers of his son Randolph and grandson Winston. Following his retirement, Churchill left for a holiday in Sicily. As he boarded the plane, he was handed a letter written in the Queen’s own hand. It is a well-known letter. Perhaps the key line is that reading: “it would be useless to pretend that either he [Anthony Eden] or any of those successors who may one day follow him in office will ever, for me, be able to hold the place of my first Prime Minister, to whom both my husband and I owe so much and for whose wise guidance during the early years of my reign I shall always be profoundly grateful.” She knew that she could always rely on “a wise counsellor” in the future.18

In response, Sir Winston said that The Queen’s letter would always be “one of my most treasured possessions.” He paid tribute to her comprehension of “the august duties of a modern Sovereign and the store of knowledge” that she had accumulated thanks to “an upbringing both wise and lively.”19

Final Years

Thus ended the formal relationship between the Queen and her first Prime Minister. But it was by no means the end of their friendship. Churchill was still able to walk in the 1956 Garter ceremony, though he confessed to his doctor: “I had to sit down during the Service. Even when they sang ‘God Save The Queen’ I did not stand up. My legs felt wobbly. It wasn’t the length of the walk that tired me, but the way they tottered along and dawdled.”20 He last lunched with the Queen and his fellow Garter Knights at Windsor Castle in 1960.

While he was able, Churchill appeared at the Cenotaph on Remembrance Sunday. In 1957, when in indifferent health, he received a letter from Sir Michael Adeane saying that the Queen did not wish him “to take the smallest risk” to his health, “by prolonged exposure to November weather.”21 Nevertheless, Churchill was able to attend the ceremony. In the same year he was indignant about Lord Altrincham’s famous journalism article “The Monarchy Today,” which, among other things, criticised the Queen’s voice in speeches.

In May 1960 Churchill gave the Queen a painting of Wilton House, where he had been a regular guest at Whitsuntide in earlier times. He was concerned for the Queen’s safety when she insisted on visiting Ghana in October 1961, but she was determined to go, and the visit passed off well, Ghana remaining in the Commonwealth.

On the tenth anniversary of the Queen’s accession, Churchill congratulated her, and she again thanked him for “the wise counsel and also friendship which I know my father valued so very much as well.”22 He admired the Queen for accepting her role of representing special values and keeping those values safe from what he called “the rancour and asperity of party politics.”

When, in January 1965, it became clear that Churchill was in his last days following a massive stroke, the Queen attended Sunday matins at St Lawrence’s Church, Castle Rising, in Norfolk. Prayers were said for the dying statesman, who passed a week later on 24 January. The Queen had one final honour to bestow: she decreed that Sir Winston be granted a State Funeral and led the mourners at St Paul’s Cathedral. These included more or less the entire British Royal Family, Kings and Queens of Europe, and figures such as President de Gaulle. Former President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies spoke on the BBC commentary. Churchill’s body was conveyed up the Thames in the launch Havengore and went later by train to Bladon, in Oxfordshire, for final burial. The Queen’s wreath bore words written in her own hand: “From the Nation and the Commonwealth. In grateful remembrance. Elizabeth R.”23

Last Things

In 2005 The Queen bestowed the Order of the Garter upon Churchill’s daughter, Lady Soames. Her Majesty told Mary Soames that she was giving her the same collar worn by Sir Winston. Mary said that that could not be because that collar was displayed at Chartwell. The Queen told her she knew this and had arranged to have the collar swapped for another one, an example of the Queen’s thoughtful attention to detail.

It may not be inappropriate to mention here that Lady Soames told the present author that she practised her steps for her investiture by the Queen at Windsor Castle. Mary would go out into her garden in her dressing gown, advance, curtsey, and then advance again, perfecting the routine. One day she looked up to spot an astonished neighbour looking down on this curious scene.

The end of the Queen’s reign marks the conclusion of a phenomenal span of time. Churchill, her first Prime Minister, was born in 1874. Two days before the Queen died at Balmoral on 8 September 2022, Her Majesty received Liz Truss, who metaphorically kissed hands as the fifteenth different person to serve as her Prime Minister. Truss was born in 1975, more than one hundred years after Churchill. The Queen’s own funeral on 19 September was the first full-scale State Funeral in Britain since Churchill’s in 1965. The Age of Churchill ended during the Second Elizabethan Age. The Second Elizabethan Age—a golden age—has now also ended.

Perhaps the last word on the Queen should be given to Sir Winston in tribute to the fine association that grew between monarch and first minister. In thanking Her Majesty for her letter to him after his resignation in 1955, Churchill wrote that she had resolved “to serve as well as rule, and indeed rule by serving.”24 This is a point that has frequently been made in the days since the Queen’s death, albeit less eloquently. There can be few finer epitaphs to the Queen, and it came from a great man.

Endnotes

1. Lord Moran, Winston Churchill: The Struggle for Survival, 1940– 1965 (London: Constable, 1966), p. 400.

2. Ibid., p. 403.

3. Ibid., p. 607.

4. John Colville, The Fringes of Power (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1985), p. 640.

5. Robert Rhodes James, ed., Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches, vol. VIII, 1950–1963 (New York: Chelsea House, 1974), p. 8342.

6. Martin Gilbert, ed., Winston S. Churchill, Companion Volume V, Part 1, The Exchequer Years (London: Heinemann, 1979), p. 1349.

7. Strand Magazine, May 1937.

8. Martin Gilbert, ed., The Churchill Documents, vol. XVI, The Ever Widening War, 1941 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2011), p. 536.

9. Martin Gilbert, ed., The Churchill Documents, vol. XVIII, One Continent Redeemed, January– August 1943 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2015), p. 1715.

10. Martin Gilbert, ed., The Churchill Documents, vol. XIX, Fateful Questions, September 1943 to April 1944 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2017), p. 2552.

11. The Times, 12 February 1952.

12. Colville, p. 642.

13. Ibid., p. 644.

14. Financial Times, 4 June 2022.

15. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, vol. VIII, Never Despair (London: Heinemann, 1988), p. 764.

16. Ibid., p. 824.

17. Ibid., p. 1124.

18. Ibid., p. 1126.

19. Ibid., p. 1127.

20. Moran, p. 555.

21. Gilbert, Never Despair, p. 1256.

22. Ibid., p. 1333.

23. Ibid., p. 1364.

24. Ibid., p. 1127

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.