Finest Hour 197

Churchill and Ireland Revisited

Lord Randolph Churchill

September 4, 2023

Finest Hour 197, Third Quarter 2022

Page 09

By Paul Bew

Paul Bew is Professor of Irish Politics at Queen’s University, Belfast and author of Churchill and Ireland (Oxford, 2016). He sits as a crossbencher in the House of Lords as Baron Bew of Donegore.

Winston Churchill entered the world of Irish politics at a decisive moment: as a young MP he witnessed the final collapse of the project of legislative union as envisaged by the Act of Union (1801) and its replacement by an entirely different concept. The original idea had been to create “one people” across two islands. Edmund Burke, Irishborn, raised, and educated, but as a politician and writer totally locked into English politics, had been the creator of this notion. He convinced William Pitt, who loved to repeat Burke’s phrase: “It was impossible to speak as ‘a good Englishman without speaking as a good Irishman’ and impossible also to speak as a ‘good Irishman without speaking as a good Englishman.’” There was a strategic dimension, of course, in the age of the Napoleonic threat, but the union was based also on a sentimental aspiration.

The Burkean conception failed in the nineteenth century. It failed because of the thirtyyear delay in implementing Catholic emancipation. It failed because the horrific Irish famine (1846–50) was at the very least a refutation of the idea that the union guaranteed prosperity. For John Mitchel (an Irish revolutionary turned militant southern slaveholder and the most influential Irish writer of the nineteenth century) it was a proof of something worse—genocidal intent. By the mid-1880s a mass democratic demand led by Charles Stewart Parnell in support of a Dublin parliament and thus a substantial modification of the union had a profound legitimacy in Ireland. One of the two great English parties—the Liberals, under William Gladstone—after 1886 supported that demand. The other great party, the Tories, flirted with it in 1885, especially inspired by Winston’s father, Lord Randolph Churchill. By 1886 the Tories decided to oppose home rule, again with Lord Randolph in the lead, now a born-again supporter of Ulster Unionism. The failure of the project to create one people across two islands became a more limited conception: the necessity to accept that there were two peoples on one island.

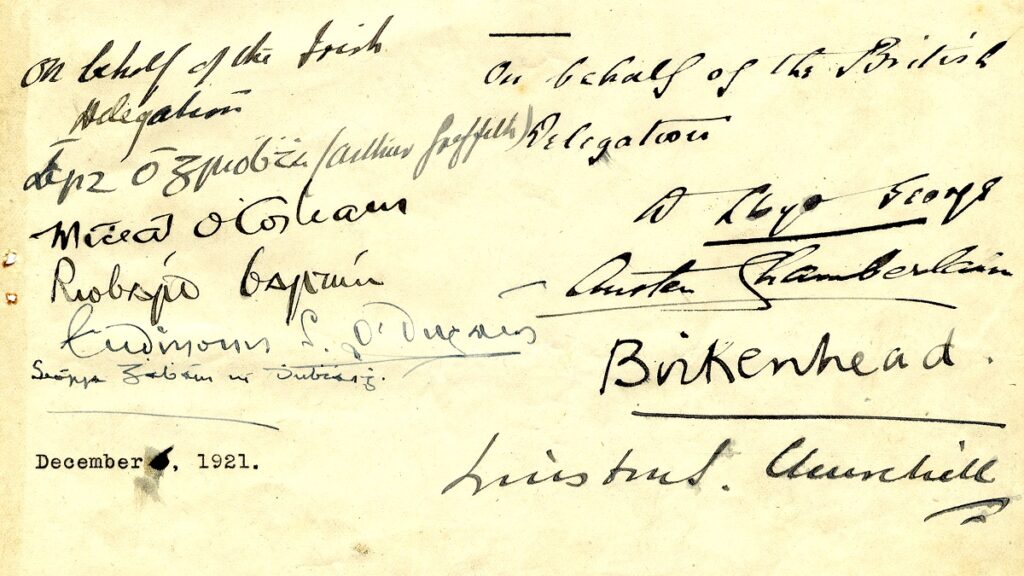

This is the defining context of Winston Churchill’s career. Initially, he was an uncomplicated Unionist and Tory. He then became a Liberal and, by 1908, a supporter of Irish home rule, but he never departed from the idea that north-east Ulster might require special treatment and be left, on the basis of consent, to sit outside the arrangement for the bulk of the island. This influenced his behaviour during the home rule crisis of 1912–14 (despite a serious attempt by a Unionist crowd to maul him in Belfast) when he was a senior member of the Cabinet. It influenced his behaviour during the Anglo-Irish war of 1919–21, when he described—as Sergeant A. M. Sullivan noted—the IRA as “organised baboonery.” Nonetheless he negotiated selfgovernment both for the Dublin and the Belfast parliaments. In the mid-1920s as Chancellor of the Exchequer, he, in effect, stabilised the long-term finances of both Irish states.

In the 1930s Churchill was a marginalised and isolated figure in British politics. He noted bitterly that now that Ireland was forgotten about in London, so was his contribution to solving the Irish question. Then in 1938 came shocking news: the UK government was handing to Ireland the strategically important “Treaty ports.” Churchill was furious but again isolated. Diarist Henry “Chips” Channon wrote:

Winston Churchill, against everything, is even against the Irish Treaty, Chamberlain’s masterly coup. Is Winston, that fat, brilliant, unbalanced, illogical, porcine orator more than that? Is he the male Cassandra? Is he perhaps right, banging his head against an uncomprehending country and unsympathetic government? I think not, for he is always wrong. Now he is a man with [a] fixed idea, i.e. the German menace. All his life he has hated and preached against them and thus done much to poison our relations with Germany.1

But to the anger and frustration of Tories like Channon, Churchill was vindicated and two years later took on the leadership of the United Kingdom.

Confession

I have here a confession to make. I think now I should have openly stated at the start of my book Churchill and Ireland (Oxford, 2016) that both my parents, one a Belfast Protestant and the other a Cork Catholic, were members of Churchill’s army in the Second World War. They were both doctors—my father, Dr. Kenneth Bew, a lieutenant in the RAF and my mother, Captain Mary “Paddy” Leahy in the Indian Medical Service, which was then an integral part of the British army and something of an Irish fiefdom.2 This is why I quite like the underlying concept of Churchill’s draft 1934 film script for movie mogul Alexander Korda, that the mixed-marriage tensions of an Irish-CatholicProtestant couple might be dissipated by a decision to join the British army.

More profoundly, as the decision of both my Irish parents to support the British war effort was the sine qua non of my existence, I have never been able to suppress my lack of enthusiasm for Irish neutrality in the war against Hitler. Perhaps as a consequence I have never been able to admire the policy of Irish neutrality. I can accept, of course, that, given the historic legacy of Anglo-Irish bitterness and tension, it may well have been politically impossible to bring Ireland into the war against the Nazis, even after the Americans joined in.

I do accept it was unfair of Churchill to speak in his 1945 victory speech of de Valera’s “frolic” with the Germans. In fact, Col. Dan Bryan, head of Irish Intelligence, was determined to make Ireland’s neutrality as beneficial to the Allies as possible, even before the American arrival in the war made British defeat considerably less likely. Other senior Irish officials had assumed it was inevitable in the summer of 1940.

I can accept that Irish people find Churchill’s tone patronising. On 5 May 1943 he wrote to Attlee, “Their [Irish] conduct will never be forgiven in the war by the British people…we must save these people from themselves.” In fact, of course, Ireland’s conduct was rapidly forgiven—in part because of the way Churchill played up the voluntary service of Irish soldiers in his wartime army.

What I cannot accept is the claim that Irish neutrality was not simply practically unavoidable but a morally desirable policy. Hitler was the orator of the most destructive thunderous racism the world has yet seen. Feared as he was, Churchill played a very significant role in stopping him. Perhaps it is the silent acknowledgement of the fact which led Tariq Ali in his new book Winston Churchill: His Times, His Crimes (reviewed in FH 196) to an unusual discretion. Ali is not embarrassed to fill up many pages with a potted version of Irish history in his indictments. But he simply does not mention Irish neutrality, still less the IRA’s pro-Nazi stance at that time, or the Irish government’s censorship of the Dublin press for its initial efforts to print the news of the concentration camps.3 This, perhaps, is not a subject for Mr. Ali to dwell upon.

There is, of course—as there always is with Northern Ireland—a dreary, prominent, sectarian side to the story even at such a pivotal moment in world history, as Dr. Marianne Elliott has pointed out in her powerful review of Simon Topping’s Northern Ireland: The United States and the Second World War.4 In 1943, Churchill said that, but for the loyalty of Northern Ireland, Britain would “have been confronted with slavery and death, and the light which now shines so strongly throughout the world would have been extinguished.”5 Churchill was thinking here, as his 1945 speech makes clear, of Northern Ireland’s strategic support for Atlantic supply lines when Britain stood alone in 1940. Even so it is hard not to sputter: but what about the Red Army or the United States war machine? On the other hand, Churchill’s words were on the tea towel in many an Ulster house when I was growing up. Kevin McNamara, the UK politician of strong nationalist sympathies who was Labour’s Northern Ireland spokesman in the 1990s, used to mock this piety. As a young man active in the civil rights movement, I tended to agree with McNamara. But what if Churchill’s words contained a significant measure of truth?

“A National Settlement”

It is remarkable how perceptive Churchill’s comments are on the big Irish issues of the nineteenth and twentieth century. On the one hand, Churchill clearly saw the need for some form of Irish self government based on a Dublin parliament. He clearly accepted that British/Dublin Castle rule had failed:

What was it that induced Lord Dudley to cast away all his prospects of future promotion in CHURCHILL AND IRELAND BELOW Dublin Castle 1 2 | FINEST HOUR the Tory party? Was it some dim understanding of a great truth which came to those who watched the working of the machine at close quarters or was it the clear apprehension of a great fraud? The Irish polity has its equal nowhere in the world….Ireland was governed by neither King nor people. The system of government was not democratic, autocratic or even oligarchical.6

In 1906 Churchill published the two-volume life of his father Lord Randolph: designed, above all, to exorcise his father’s long humiliating public death by embracing and explaining his career. Inevitably it dealt with Irish matters. The young Churchill laid considerable emphasis on his father’s attempt to form an alliance with Parnell in 1885.7 After that attempt failed, however, Lord Randolph turned against home rule, creating a quandary for his son’s efforts at filial piety twenty years later. In his study of Winston Churchill’s writings, Peter Clarke explains that “By 1906, after all, a newly minted Liberal, he [Winston] was himself under pressure to support home rule. This is perhaps the single most embarrassing political dilemma that the biography has to confront.”8 A key passage resolved the problem:

A proposal to establish by statute, subject to guarantees of Imperial supremacy, a colonial parliament in Ireland for the transaction of Irish business may indeed be unwise, but is not, and ought not to be, outside the limits of calm and patient consideration. Such a proposal is not necessarily fraught with the immense and terrific consequences which were so generally associated with it. A generation may arise in England who will question the policy of creating subordinate legislatures as well as we question the propriety of catholic emancipation and who will study the records of the fierce disputes of 1886 with the superior manner of a modern professor examining the controversies of the early church. But that will not prove the men of 1886 wrong or foolish in speech and action.9

On 4 May 1908 Churchill told the Kinnaird Hall in Dundee:

With these facts before us, upon the authority of men like Lord Dunraven, Sir Joseph West Ridgeway, Sir Anthony MacDonnell, Lord Dudley, and others who have served the Crown in Ireland—is it wonderful that we should refuse to turn our eyes away from the vision of that other Ireland, that Ireland free to control her own destiny in all that properly concerns herself; free to devote the native genius of her people to the purposes of her own self-culture, the vision of that other Ireland which Mr Gladstone had reserved as the culminating achievement of his long and glorious career?— [Cheers.] Is it wonderful that we should refuse to turn our eyes away from that? No, I say that the desire and the aim of making a national settlement with Ireland on lines which would enable the people of that country to manage their own purely local affairs is not an aim that can be separated from the general march of the Liberal army. [Cheers.]10

But, despite this flourish, it is important to note that Churchill was well aware of the flaws in Gladstone’s Irish policy: even as he understood and respected it. Churchill brilliantly pointed out—correctly—that Gladstone’s view of Parnell’s emotional conservatism was part of the logical reason for the G.O.M.’s conversion to home rule. But even so, in his essay on Joseph Chamberlain, Churchill pointed out with great precision:

Gladstone was blind to the claims and cause of Protestant Ulster resistance. He displayed an indifference to the rights of the people of Northern Ireland which dominated the liberal mind for a whole generation. He elevated this myopia to the level of a doctrinal principle. In the end we all reached together a broken Ireland and a broken United Kingdom.11

Churchill was aware of England’s brutal history in Ireland in the early modern period. In early December 1921, Harold Laski, the LSE don, reported a

conversation with Churchill, in which Churchill was full of threats of John Bull laying about with a big stick. We had utterly broken rebellion in the sixteenth century. Why not now with vastly greater power? Yes, replied Laski, but the condition of Ireland today is the result of our policy then.12

Within days Laski and Churchill were working together on the details and language of the treaty compromise.13 In other words, Churchill well understood that the darker pages of Irish history could not act as a political guide in the twentieth century.

Deep Thought

In short, it is not possible to dismiss Churchill as someone with an ignorant, prejudiced view of Irish history. Consider his brilliant assessment of the great nineteenth century nationalist leader Parnell, which still dominates contemporary historiography:14

Yet, he [Parnell] was himself a man of Conservative instincts, especially where property was concerned. Indeed, the paradoxes of his earnest and sincere life were astonishing: a Protestant leading Catholics; a landlord inspiring a “No Rent” campaign; a man of law and order exciting revolt; a humanitarian and antiterrorist controlling and yet arousing the hopes of Invincibles and Terrorists.

Churchill added:

Without Parnell, Gladstone would never have attempted Home Rule. The conviction was borne upon the Grand Old Man in his heyday that here was a leader who would govern Ireland, and no one else could do it. Here was a man who could inaugurate the new system in a manner which would not be insupportable to the old.15

Why discuss Churchill’s history writing in this way? Precisely because Churchill is so impulsive and, at times, such an unwisely verbose figure, it is important to note that he had a sharp analytic mind, and his Irish politics were based on a profound level of understanding. He seems to leap about the place—one time a sharp critic in 1914 of Edward Carson’s leadership of Unionism and then Carson’s friend in 1916; Michael Collins was the leader of “organised baboonism” but again soon a real ally.

Some of this is “normal” political opportunism, but it is also compatible with Churchill’s long term considered writing on the Irish question. There is a reason why Churchill’s record on Ireland is—for all his critics— more substantive and enduring than other British premiers, including Gladstone. It is because he had thought more deeply about the Irish question than any other British Prime Minister. His emphasis on “consent” as the necessary building block of an Irish settlement is echoed very precisely in the Good Friday Agreement. Winston Churchill would not have been surprised.

Churchill had, after all, insisted in his Belfast speech of 1912—and lived up to it when he became Chancellor in 1925—that devolution within the UK could not deprive any region of the UK of the benefits of economic and social parity, in other words, a subvention (now at £15 billion pounds per annum to Northern Ireland). Despite many political excitements this has made for the stability of the UK and continues to make for it.

Endnotes

1. Simon Heffer, ed., Henry “Chips” Channon: The Diaries, vol. I, 1918–38 (London: Hutchinson, 2021), pp. 863–64.

2. Greta Jones, “Doctors for Export”: Medical Migration from Ireland, c. 1860 to 1960 (Leiden: Brill, 2021), p. 223.

3. The Observer, 8 May 2005.

4. Times Literary Supplement, 24 June 2022.

5. Paul Bew, Churchill and Ireland (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), p. 556.

6. Hansard, 20 February 1905, vol. 141, col. 712.

7. Winston S. Churchill, Lord Randolph Churchill, 2 vols. (London: Macmillan, 1906), vol. I, p. 305.

8. Peter Clarke, Mr Churchill’s Profession: Statesman, Orator, Writer (London: Bloomsbury, 2012), p. 206.

9. Churchill, vol. I, p. 436.

10. Robert Rhodes James, ed., Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches, vol. I, 1897–1908 (New York: Chelsea House, 1974), p. 1027.

11. Winston S. Churchill, Great Contemporaries (London: Thornton Butterworth, 1937), p. 88.

12. Trevor Wilson, ed., The Political Diaries of C. P. Scott, (London: Collins, 1970), entries for 2–5 December 1921.

13. Mark DeWolfe, ed., Holmes– Laski Letters: The Correspondence of Mr Justice Holmes and Harold J. Laski 1916–1935, vol. I (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1953), pp. 386–87.

14. See Roy Foster, Parnell: The Man and His Family (London: Hassocks, 1997); J. Leersen, ed., Parnell and His Times (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021); and Paul Bew, Ancestral Loyalties in Irish Politics: Dillon and Parnell (Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming).

15. Churchill, Great Contemporaries, pp. 346 and 348.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.