Finest Hour 196

“We Tender Our Most Grateful Thanks”

Emir Abdullah, Sir Herbert Samuel, Winston and Clementine Churchill, Jerusalem, 1921

April 26, 2023

Winston Churchill’s 1922 White Paper for Palestine

Finest Hour 196, Second Quarter 2022

Page 32

By Sarah Reguer

Sara Reguer is Professor Emerita at Brooklyn College, CUNY. This article is based on her book Winston S. Churchill and the Shaping of the Middle East, 1919–1922, Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2020.

When Winston Churchill was appointed Secretary of State for War and Air in 1919, he was tasked with two major things: demobilizing and economizing. He set to work with his usual enthusiasm and creativity, only to discover that there was one geographic area in which he made no progress, namely the Arab provinces of the defeated Ottoman Empire. The complications connected to this part of the world included the fact that three government offices claimed those provinces as theirs—the Foreign Office, the India Office, and the Colonial Office. France also claimed part of the region based on wartime agreements, but so did the Sharifians and the Zionists. At the same time, not only had the Turks not signed a peace treaty, but a nationalist force was also growing in Eastern Anatolia. To top it off, the Bolsheviks were expanding their power into the Middle East.

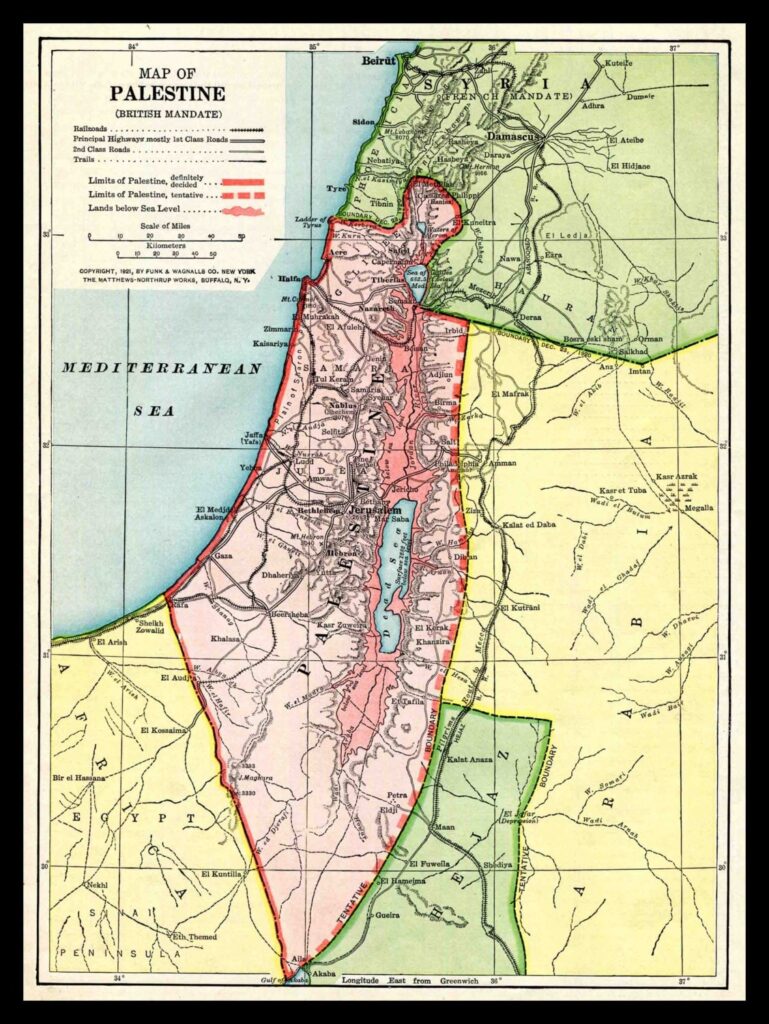

After two years of frustration, Churchill convinced the government to put the Middle East provinces under the control of the Colonial Office. He was then appointed Colonial Secretary, again with the tasks of demobilizing and economizing. The first thing that Churchill did was to call for a conference of the British Middle East experts to meet in Cairo and discuss how to deal with the British-controlled areas of Iraq and Palestine. These experts had to keep in mind that, even though the British armies had conquered the areas during the First World War, in the new world order of the League of Nations, the British were only mandated control of these territories with the task of educating the people in democratic practices, such as developing representative institutions, until they were ready to rule themselves.

The agenda for the Cairo Conference was drawn up in London, and then specialists in Cairo worked out the details of the new Middle East policy. The focus was on using air power, local gendarmeries, and cheap Indian troops, as well as supporting members of the Sharifian family—Feisal in Iraq and Abdullah in TransJordan. But as 1921 progressed, Churchill’s optimism about Palestine waned. Despite his many declarations of sympathy for Zionism, he was annoyed. His annoyance manifested itself in his relations with High Commissioner Sir Herbert Samuel, the Arabs, and the Zionists, but mostly in his lack of action. As Colonial Secretary, his inaction influenced events and ideas.

Immovable Forces

There is no one document that one can cite to answer the question of why Churchill behaved as he did. The answer lies in a feeling generated by all the documents relating not only to Palestine but to the Middle East generally. Churchill, the master of argument and cajolery, found himself faced with immovable forces in the shape of the Arabs and Zionists. He could accept such opposition from Englishmen holding views differing from his own. He could accept it from other Europeans. But he could not accept it from peoples of backward areas for which Britain was burdened with the task of bringing into twentieth-century modernity.

Churchill’s task was to economize, which could take place only in a peaceful country. He discovered, after trying to cope with the Zionists and the Palestinian Arabs, that doing nothing seemed to bring a semblance of peace. He mastered the varied arts of procrastination, such as deferring action until another oral report was submitted, ignoring requests for action, or refusing outright to act yet.

At the end of 1921 Churchill did act on issues connected with the Palestine garrison, but High Commissioner Samuel kept writing about the need for a clear political policy, since the political status was still not regularized by a formal document, either a British one or one from the League of Nations.

Memoranda arrived from Samuel, from leading members of the Colonial Office’s advisory board, from Dr. Chaim Weizmann, president of the World Zionist Organization, and from the Arab delegation. On 11 August, Churchill wrote an introduction to a Palestine memorandum that was not very encouraging nor optimistic. “The situation in Palestine causes me perplexity and anxiety,” he began.1 “The whole country is in a ferment. The Zionist policy is profoundly unpopular with all except the Zionists.” Both sides were arming, elective institutions were refused in the interests of the Zionist policy, “and the high cost of the garrison is almost wholly due to our Zionist policy.”2 Meanwhile, even the Zionists were discontented at the lack of progress and the “chilling disapprobation” of the British officials and the military.

Possibly Churchill was ready to back out of the Balfour Declaration if the Cabinet so decided. But he did not press the case strongly at the Cabinet meeting, and discussion was adjourned. He also did not authorize Weizmann to make any fresh declaration of policy on behalf of the British Government at the Carlsbad Zionist Congress, but merely sent an innocuous telegram wishing it well. Churchill also ignored Samuel’s telegrams begging for action, even after the violence in Jerusalem on the anniversary of the Balfour Declaration. Weizmann plowed ahead, however, and came to an agreement with the Colonial Office in October on how to ration out visas to new Jewish immigrants, how to ensure that they were politically, socially, technically, and physically qualified. The Colonial Office also agreed to reestablish a “certificate system” whereby any Jew in possession of a Zionist Organization certificate that work was available for him in Palestine would be admitted into the country.

Yet everyone agreed that the major initiative for defining policy had to come from London, but London and Churchill seemed to favor inaction, and so 1921 drifted to a close.

The White Paper Takes Shape

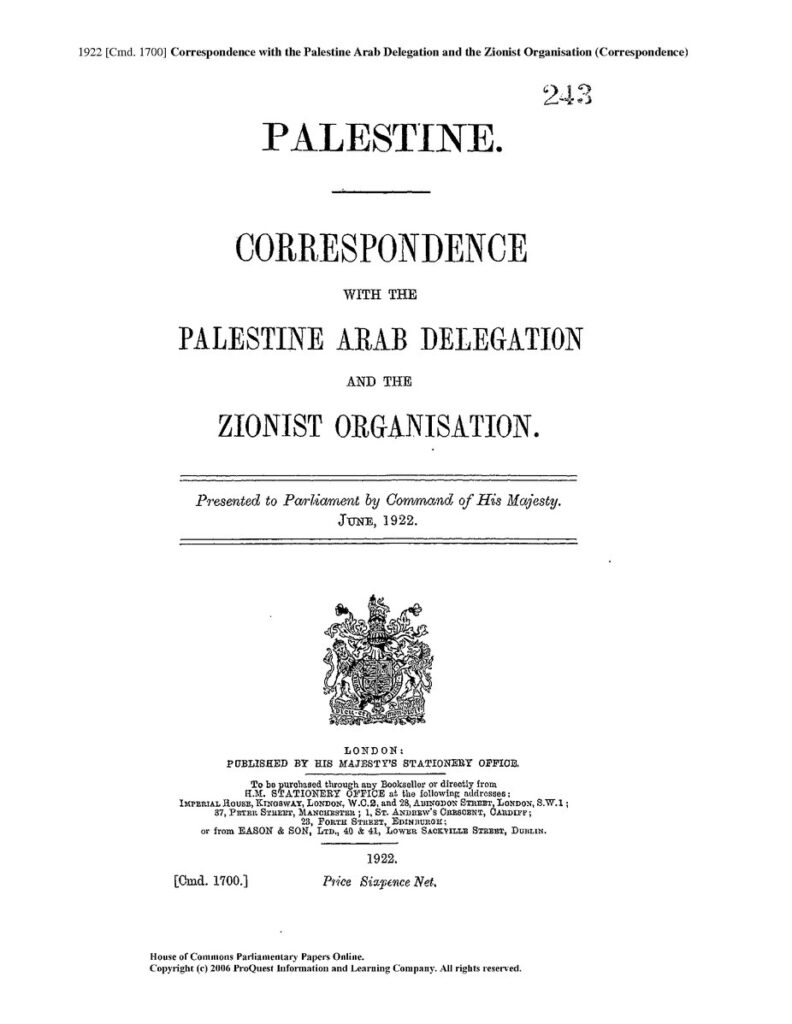

1922 proved to be a busy year, and the Colonial Secretary was content to leave Palestine affairs in the capable hands of Sir Herbert Samuel and the Middle East Department. Churchill had already shown them what he wanted, and so, as they presented various memoranda to him, he merely initiated each item in concurrence. Slowly a formally designed policy of the British government based on the Balfour Declaration began to take shape. Although the final result came to be known as the Churchill White Paper (formally it was titled Palestine: Correspondence with the Palestine Arab Delegation and the Zionist Organisation), Churchill did not actually write the statement of policy himself.

The focus of Churchill’s attention at the start of the year was to reduce the cost of the military presence in Palestine. Economizing was also behind his action in connection with Trans-Jordan. This was necessary because in March he had to present the Middle East estimates to Parliament. When he did so, he focused on the drop in the expenditure in Palestine and predicted further reductions. At the behest of the Middle East Department, he added a declaration of policy that because of British pledges to carry out Zionist policy, which included Jewish immigration, there was a difficult situation there, but “I am bound to retain in the hands of the Imperial Government the power to carry out those pledges.”3 As a statement of policy, however, this was much too general.

The Palestine Arab delegation, which was in London, met numerous times with members of the Middle East Department, and the correspondence went back and forth. No matter how carefully the British position was explained to them, the Arab delegation refused point blank to accept any constitution that would fall short of giving them full control of their own affairs, and they repeated over and over that the British had to repeal the Balfour Declaration and prevent a flood of “alien” Jewish immigration.

Sir Herbert Samuel arrived in England in April to confer with the Colonial Secretary on finances and to attempt to work out a political settlement that would satisfy the reasonable claims of all parties. He proposed to draw up, in consultation with the Middle East Department, a statement of policy covering all points at issue. He suggested showing the statement informally to both the Zionists and the Arab delegation and doing his best to get them to accept it in advance.

Samuel dictated a preliminary draft and worked closely with John Shuckburgh of the Middle East Department on the final drafts. The two men were sure both that the Zionists would accept the statement and that the Arab delegation would not. Churchill then authorized Samuel to approach both parties informally. Weizmann was immediately sent a copy, and the Arab delegation a few days later. Shuckburgh showed the draft to Weizmann, who happened to drop by to see him that afternoon, and Weizmann assured Shuckburgh that the Colonial Office should receive a reply intimating Zionist acceptance. “He was on the whole in good spirits, and is taking his basin of gruel with a better grace than I expected,” noted Shuckburgh, who was referring to the sections of the policy statement that displeased and disappointed the Zionists.4

Backroom Dealing?

The question to be asked is why Weizmann was ready to go along with such a policy. The answer seems to lie in the private conversations that Weizmann had with Churchill, for there is no written record of these conversations. Churchill admired Weizmann and recognized both his intellectual and diplomatic abilities. He agreed with Weizmann’s analysis of Pinchas Rutenberg’s huge plan for developing Palestine by building hydroelectric plants along the Jordan River and its tributaries. Churchill had met Rutenberg on his trip to Jerusalem right after the Cairo Conference and had been impressed by both the man and the plan. Sound economics were the basis of any development in Palestine, and Weizmann recognized this.

What cannot be documented is that, somewhere in these private conversations, Churchill may have hinted at the fact that two documents of policy were being written at the same time: British policy for Palestine and the mandate document for the League of Nations. Both were vitally important, and it could very well be that the hint that Churchill would include the Balfour Declaration in the League document if the Zionists went along with the White Paper played a role in Weizmann’s actions. Including the Balfour Declaration in the League’s document would mean international recognition of the legitimacy of the Zionist claim to a national homeland, based on its historic connections to Palestine.

The Fine Print

Turning first to the Arabs, the White Paper declared that Arab apprehensions in Palestine were based on exaggerated interpretations of the meaning of the Balfour Declaration. The British Government had no aim to create a wholly Jewish Palestine nor had it ever contemplated the disappearance or subordination of the Arab population, language, or culture in Palestine. The wording of the Balfour Declaration did not contemplate that Palestine as a whole should be converted into a Jewish National Home, but that such a Home should be founded “in Palestine.”

The Jewish population was apprehensive that Britain would depart from the policy embodied in the Balfour Declaration. Those fears were unfounded. After a brief description of the accomplishments of the Jewish community to date, the question raised by so many different people is openly asked: what is meant by the development of the Jewish National Home in Palestine? The documents reads, “…it may be answered that it is not the imposition of a Jewish nationality upon the inhabitants of Palestine as a whole, but the further development of the existing Jewish community, with the assistance of Jews in other parts of the world, in order that it may become a center in which the Jewish people as a whole, may take, on grounds of religion and race, an interest and a pride.”5 But to achieve this, it was essential that the Jewish people should know that it was in Palestine as of right and should be internationally guaranteed and recognized to rest on ancient historic connection.

To fulfill the policy of developing a Jewish National Home it was necessary that the Jews should be able to increase their number by immigration. “This immigration cannot be so great in volume as to exceed whatever may be the economic capacity of the country at the time to absorb new arrivals.”6 The immigrants could not be a burden on the Palestinians as a whole, nor should they deprive any section of its employment. Politically undesirable people would be excluded. It was intended to set up a special committee in Palestine consisting of members of the newly elected legislative council to confer with the Administration on matters relating to the regulation of immigration.

Another point needing clarification was the Arab claim that Palestine was included in Egyptian High Commissioner Sir Henry McMahon’s wartime promise to Sharif Hussain of Mecca of an independent Arab state, a claim firmly denied. Nevertheless, it was Britain’s intention to foster self-government in Palestine, but gradually. The first step was establishing the nominated Advisory Council. It was now time for the second step, establishing a legislative council containing a large proportion of members elected on a wide franchise. Before further self-government was extended, and the Assembly placed in control over the Executive, some time should elapse to enable the institutions to become well established and to gain experience.

A policy on these lines, the gradual attainment of self-government coupled with religious liberty, was most commendable and was the best basis upon which to build the spirit of cooperation so necessary for further progress.

Churchill and the Middle East Department were satisfied with the new policy paper and worked out the details of communicating with the parties concerned and the procedure needed to get the needed Parliamentary approval for a new policy. Only then would the League of Nations Council be officially informed, so that the League could then vote on the detailed Palestine mandate document.

“You Have No Right”

The event that knocked Churchill out of his passive role was the passage in the House of Lords of a resolution against the Balfour Declaration on 21 June. The anti-Zionists mustered their forces, particularly to denounce the Rutenberg concession, which they saw as the beginning of Jewish domination in Palestine. This resolution was dangerous for Palestine policy, and Churchill knew that he would have to ask for a vote of confidence from the House of Commons specifically upholding the Balfour Declaration.

On 4 July 1922 Churchill rose in the House of Commons to defend his Palestine policy. He was addressing a Parliament that was wavering in its backing of the 1917 pledge. He immediately asked whether or not Parliament would keep its 1917 pledge. Then he asked whether the measures being taken by the Colonial Office to fulfill that pledge were reasonable and proper. To those opposed he directed his fire: You have no right to say this kind of thing as individuals.

You have no right to support public declarations made in the name of your country in the crisis and the heat of the War, and then afterwards when all is cold and prosaic, to turn around and attack the Minister of the Department which is faithfully and laboriously endeavoring to translate these perfervid enthusiasms into the sober, concrete facts of dayto-day administration. I say, in all consistency and reasonable fair play, this does not justify the House of Commons at this stage in repudiating the general Zionist policy.7

Were the measures being taken by the Colonial Office reasonable and proper? The prime focus of attention was the proposed Rutenberg undertaking to build an ambitious hydroelectric project which would electrify the JaffaJerusalem railroad, among other things. This would be economically advantageous to the whole country. Coming to the crux of the issue, Churchill faced his audience:

I come to Mr. Rutenberg himself. He is a Jew. I cannot deny that. I do not see why that should be a cause of reproach….It is hard enough…to make a New Zion, but if, over the portals of the new Jerusalem, you are going to inscribe the legend, “No Israelite need apply,” then I hope the House will permit me to confine my attention exclusively to Irish matters.8

Churchill felt that he had to ask for the vote on the Colonial Office estimates to be taken as a vote of confidence for the Palestine mandate. He received it; the vote was 292 to 35.

The League Decides

After a bit of brief scuffling with the anti-Zionists, Churchill was then ready to submit the Palestine mandate to the League of Nations. Now, Churchill had to deal with some intergovernmental squabbling over specific issues. America would not approve the mandate unless it embodied a treaty that would ensure American privileges there. Italy was against the League Council appointing the Palestine Holy Places Commission and its chairman. The Vatican was against Britain’s plan of having non-Christians form the majority on the Holy Places Commission.

Churchill agreed to America’s demand. The Vatican demand resulted in reformulating Article 14. As for Italian claims, Britain promised not to obstruct Italian claims for economic concessions but refused to budge on the Holy Places Commission. Italy finally agreed. On 22 July the Council of the League of Nations convened and, after six hours of discussion, finally approved both the Palestine and Syrian mandates. On 24 July they became official.

The mandatory instrument legalized the Jewish National Home by quoting the Balfour Declaration in the preamble, and recognizing the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine. The mandatory power—Great Britain—was responsible for developing self-governing institutions, and a Jewish agency would advise the Administration. The Administration would facilitate Jewish immigration, be responsible for the Holy Places, and keep peace and order. The twenty-eight articles detailed everything including recognizing English, Arabic, and Hebrew as the official languages of Palestine. Article 25 cut off Trans-Jordan from Jewish settlement. What is missing is a date for terminating the mandate.

Weizmann immediately wrote a short congratulatory letter to Churchill:

To you personally, as well as to those who have been associated with you at the Colonial Office, we tender our most grateful thanks. Zionists throughout the world deeply appreciate the unfailing sympathy you have consistently shown towards their legitimate aspirations and the great part you have played in securing for the Jewish people the opportunity of rebuilding its national home in peaceful cooperation with all sections of the inhabitants of Palestine.9

Knowing how well Weizmann knew the inner workings of the Colonial Office, this letter might have been written a bit tongue in cheek. He knew that throughout 1922 Churchill had been intimately concerned only with the military and monetary aspects of Palestine policy and had left almost everything else to his Middle East Department and Sir Herbert Samuel. Weizmann could not have been too happy that the economic absorptive capacity idea had become formal British policy, for, as it was worded, there was no clear indication of how it would be defined. Yet it was a logical thing to write: 1922 was a culmination of Churchill’s earlier plans for Palestine. He had designed the machine and set it going and felt that he could leave it to others to tend. Also, it was Churchill who had stood up and defended the Palestine policy in Parliament and obtained the much-needed vote of confidence. More important, nothing the Middle East Department wanted to do could be done without the Colonial Secretary’s initialed sanction, albeit at times offhanded. So Weizmann’s letter of thanks was appropriate.

Legacy?

In retrospect the question to be asked is: did the Churchill White Paper of 1922 have any real impact on the development of the Jewish National Home, and, if so, how? The response is clearly that it did, but this must be viewed within the context of the time. It must be seen as a development in parallel to the mandate document. It also must be seen as an attempt by the Colonial Office to deal with the unusual situation of having to satisfy three parties: the British mandatory power, the Palestine Arabs, and the Zionists—and not just the two parties of the other mandates, namely the mandatory power and the local population. This overview attempts to clarify how this took place.

Did the White Paper pare down the Balfour Declaration? In a way it did—by emphasizing that the Jewish National Home would be in Palestine (and not all of Palestine) and limiting immigration by the principle of the country’s economic absorptive capacity. But in a way it did not—by ensuring that the Balfour Declaration be recognized by the League of Nations, emphasizing the historic connection of the Jews to Palestine. Yes, it limited immigration, but economic development was viewed by all parties as basic to moving forward.

Churchill helped mold Palestine policy—and Middle East policy in general—at a time when it was at its most malleable. He really did think that what he was doing was best for Great Britain and for the Middle East. Whether for good or ill, Winston Churchill as an individual did help shape the contours of the Middle East.

Endnotes

1. Memorandum of the Secretary of State for the Colonies, “Palestine,” 11 August 1921, CP 3213, Cabinet Papers 24/127, National Archives, London.

2. Ibid.

3. Churchill to Clementine Churchill, 4 Feb. 1922, Churchill Papers, Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge.

4. John Shuckburgh to Herbert Samuel, 3 June 1922, Colonial Office 733/34, National Archives.

5. Letter no. 5, Colonial Office to Zionist Organization, 3 June 1922, CP1700, Churchill Papers.

6. Ibid.

7. 4 July 1922, Parliamentary Debates, Commons

8. Ibid.

9. Weizmann to Churchill, 26 July 1922, Chaim Weizmann Archives, Rehovot, Israel.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.