Finest Hour 196

The Incredible Gertrude Bell

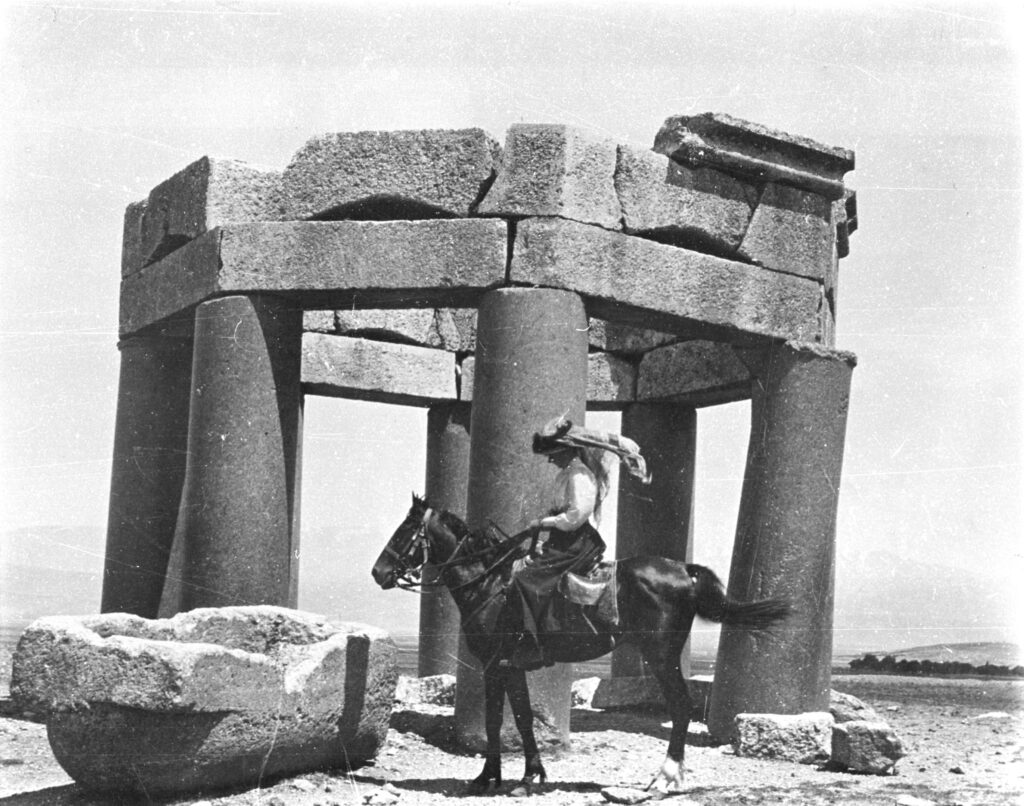

Gertrude Bell at Duris, Lebanon, June 1900. Newcastle University A_340

May 21, 2023

Finest Hour 196, Second Quarter 2022

Page 18

By David Freeman

David Freeman is editor of Finest Hour.

For more information, please visit Newcastle University’s Gertrude Bell Archive online at www.gerty.ncl.ac.uk

Gertrude Bell was one of the most amazing people about whom you probably know very little. Although she is mentioned in all of the standard Churchill biographies as being one of those who advised the Colonial Secretary during the seminal 1921 Cairo Conference, she become overshadowed in history by one of the other advisers Churchill had with him, T. E. Lawrence.

Undoubtedly, Hollywood is partly to blame. In her own time, Bell was much better known than Lawrence. That started to change in early 1920, when American journalist Lowell Thomas launched his retooled live presentation With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia, making the enigmatic Lawrence the star of the show. The legend was born.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Forty years later, the legend of Lawrence eclipsed all but Churchill among his contemporaries with the spectacular success of David Lean’s 1962 Oscar-winning film Lawrence of Arabia. Only in 2015 did Hollywood get around to making a movie about Bell. It flopped. Despite having a first-rate cast featuring Nicole Kidman in the lead, a generous budget, and dazzling scenery, the storyline lacked focus. Queen of the Desert sank so quickly that few ever knew it existed. Bell deserved better.

Progressive Patrician

Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell was born in County Durham on 14 July 1868. Her grandfather, Sir Isaac Lowthian Bell, had made a vast fortune in the iron industry, which led him to become both a baronet and a Liberal Member of Parliament. Sir Isaac and his son Hugh, the second baronet and father of Gertrude, both had progressive views by the standards of the time. This opened the way for Gertrude to attend Lady Margaret Hall and become the first woman ever to earn a first class honours degree in Modern History at Oxford.

Bell’s fierce energy and intelligence enabled her to become a trailblazer for women in the early twentieth century. In one area of life, however, she could never achieve satisfaction. The men to whom she was most attracted were already married. To make matters worse, her greatest love, Lt. Col. Charles Doughty-Wylie VC, was killed at Gallipoli. In the end, Bell never married or had children. Instead, she threw herself into her work.

The family’s enormous wealth made it possible for Bell to pursue the interests of her choice. In addition to becoming a popular travel writer, she became a skilled mountaineer and scaled many peaks in the Alps, several of which were never known to have been climbed before by anyone— male or female. She achieved a personal goal when one of these virgin peaks was named for her, Gertrudespitze (Gertrude’s Peak). After she succeeded in climbing the mighty Matterhorn in 1904, however, Bell turned away from Switzerland to embrace her greatest love, the Arabian desert.

Khatun

Bell had a gift for languages and had become fluent in several, including Persian, before she turned to Arabic, which proved much more difficult for her to master than any mountain. But master it she did. Her attraction to the people and the land compelled her to persevere. Like Lawrence, whose Arabic was never as good as hers became, she started in the Middle East as an archaeologist, but her growing knowledge of the region ultimately made her an important source of intelligence for British authorities, both civil and military.

Even during her own life, Bell began to be known as the “Queen of the Desert.” With great deference, people referred to her as “Khatun,” which means “queen” in Persian and “noble lady” in Arabic. And no wonder: on her journey through Arabia, she travelled in a manner which biographer Georgina Howell described as “little short of majestic.”1 The Bell family fortune made it possible, and Gertrude undoubtedly enjoyed traveling in style, but there was purpose in her method.

Howell explains that the Bedouin tribes judged Bell’s “status by her possessions and her gifts,” and treated her accordingly. Bell “packed couture evening dresses, lawn blouses, linen riding skirts, cotton shirts, a fur coat that would double as a blanket, sweaters, scarves, and canvas and leather boots. Beneath layers of petticoats she hid guns, her two cameras and film, and many pairs of binoculars and pistols as gifts for the most important sheikhs. She carried Egyptian cigarettes, insect powder, a Wedgwood dinner service, silver candlesticks and hairbrushes, crystal glasses, linen and blankets, folding tables, and a comfortable chair….She also brought her traveling canvas bath for when there was enough water.”2

Like Churchill, who would have approved of her style and whom she had briefly met at the start of the twentieth century, Bell had red hair. Her appearance, then, amidst her luxury caravan moving across the desert sands of the Biblical world in the Edwardian era must have looked like something from the tales of Scheherazade. The Druze chief Yahya Beg is reported to have asked, “Have you seen a queen travelling?”3 Indeed, simply reaching the lands of the notoriously clannish Druze was one of Bell’s many remarkable achievements.

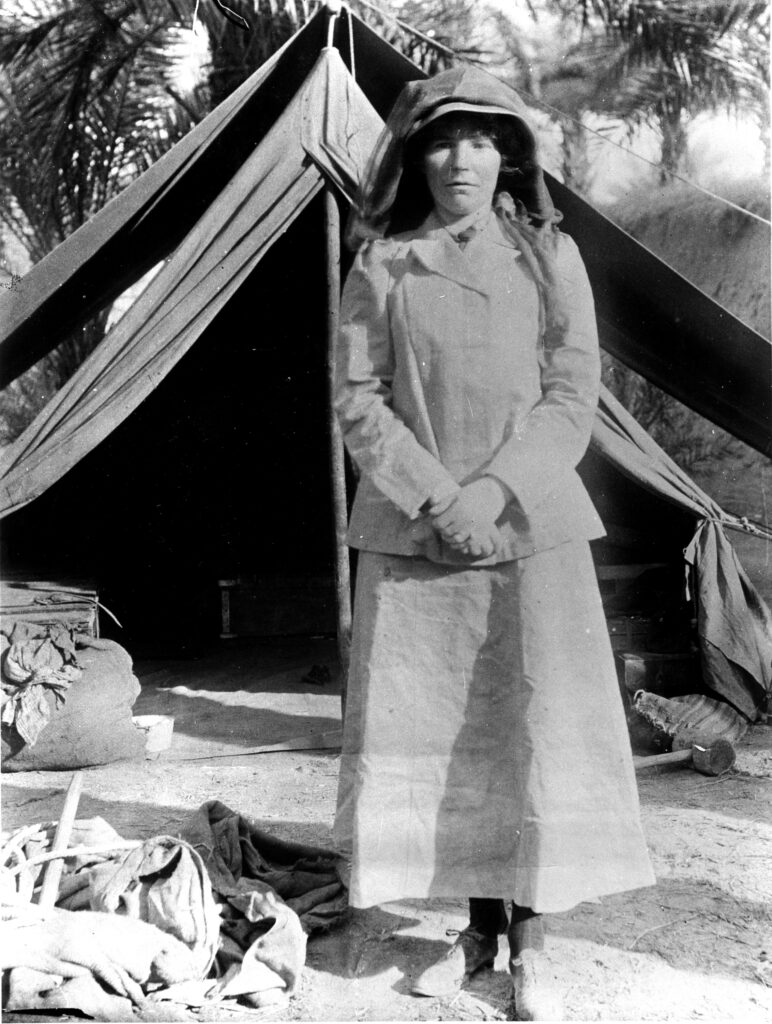

The Arab Bureau

When the Great War started in 1914, Bell initially worked for the Red Cross back home in Britain trying to trace soldiers who had become lost, which often meant captured or killed, and connect them with the families that were searching for them. Bell so impressed authorities with her organizational abilities that the government soon decided that someone with such skills and an encyclopedic knowledge of the contemporary Arab world was better suited under the circumstances to military intelligence.

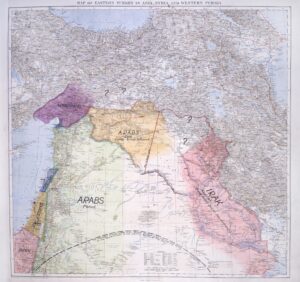

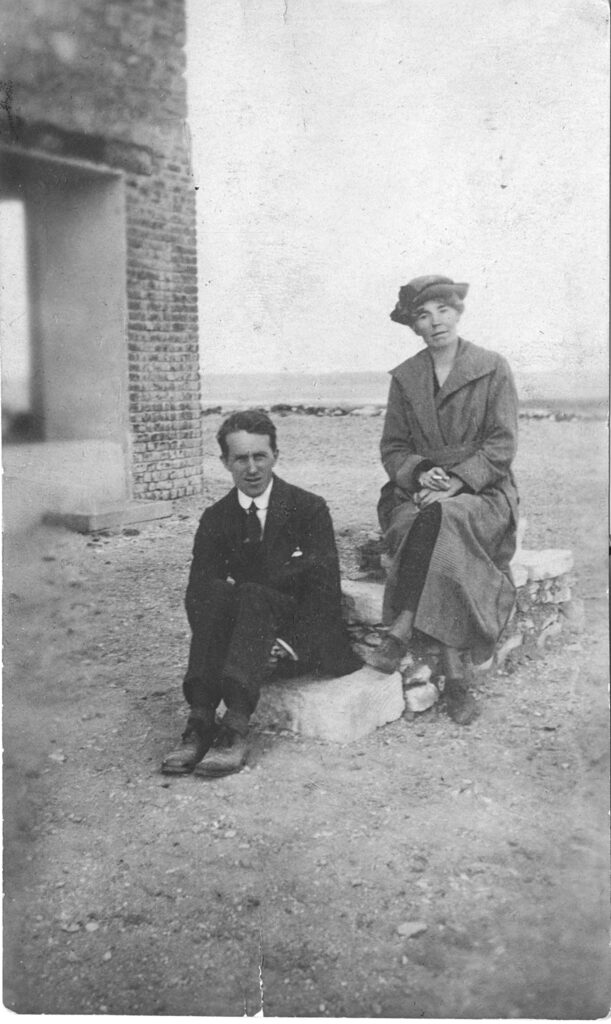

By November 1915 she was in Cairo as “Major Miss Bell,” working alongside Lawrence and others at the Arab Intelligence Bureau. Their job was to keep the British army informed of happenings among the Arabs, who were starting to be viewed in London as a means for bringing down the Ottoman Empire from within. Before long Bell was in Basra as the British tried, disastrously at first but subsequently with success, to roll up the Turks through Mesopotamia.

By the end of the war, Bell’s unparalleled knowledge of what was starting to become known as Iraq made it essential that she be one of the “forty thieves” Churchill gathered at Cairo in March 1921 to decide the future of the formerly Turkish lands then occupied by the British. Mark Jackson describes Bell’s participation in the conference in the following article.

One of the many details that had to be dealt with at Cairo was the future of Mosul. Interestingly, Churchill favored independence, believing that a Kurdish state would serve as an important buffer between the Arabs and the much-reduced Turkey. According to Bell biographer Janet Wallach, Churchill “feared that an Iraqi ruler ‘might ignore Kurdish sentiment and oppress the Kurdish minority.’”4

Lawrence supported Churchill, but Bell insisted that Mosul would be vital to Iraq not only as a source of oil and grain, but as a means of including a sufficient number of Sunni Moslems to balance the Shiite majority in the south. She believed that the Kurds would be happy to join the Arab government. When Lawrence demurred, she jeered at him, “You little IMP!” The 5’ 5” Lawrence, shorter than Churchill, retreated into silence.5

Iraq

On one point Bell and Lawrence were in complete agreement: both supported making the Emir Feisal the first King of Iraq. Feisal was of the House of Hashem, which claimed descent from the Prophet Mohammad. His father, Hussein, had been the Emir (also known as the “Sharif”) of Mecca under the Turks, but with British support had agreed to declare independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1916. Of Hussein’s sons, Feisal had worked most closely with the British during the war. He was also widely viewed as much the most impressive member of the family, although his older brother Abdullah could not be ignored and would be established as the first King of Jordan.

Feisal hoped to establish himself in Damascus as the leader of a new Arab state centered in Syria. After the war, however, the French zealously stood on their claims established with the British in 1916 under the infamous Sykes-Picot agreement. This effectively granted France control over Syria and Lebanon. When the British were forced to acquiesce in this after the Armistice, Feisal was driven from Damascus by the French, whose legacy of grotesque misrule in the region continues to affect the world today.

Meanwhile, Feisal had become “available,” and although he was not native to Mesopotamia, Bell and Lawrence were convinced that he was ideally suited to manage the fragile balance of interests that would exist in the proposed nation of Iraq. At Cairo, Churchill asked, “Can you make sure he is chosen locally?” Western political methods, Churchill added, were “not necessarily applicable to the East and the basis for the election should be framed.”6

In short, Churchill required that the selection of Feisal as king had to be seen to come from the people of Iraq and not as the actions of the British. Bell worked tirelessly to achieve this. She met again and again with the tribal leaders of the region and negotiated a delicate understanding that fulfilled Churchill’s stipulations.

After the installment of Feisal as king, Bell devoted herself to the foundation of the Baghdad Archaeological Museum, later renamed the Iraqi Museum. She saw to it that the choicest antiquities turned up by archaeologists working in the new nation found their way into the national museum. Due to the British connection, exhibits have always been presented in both Arabic and English.

Throughout her life, Bell chain-smoked Egyptian cigarettes. By 1926, the habit finally caught up with her health. She died in Baghdad from an overdose of sleeping pills on 12 July, just two days before her fifty-eighth birthday. It may not have been suicide, but she was known to be in pain, her younger brother had just died of typhoid, and the family fortune had finally been exhausted. She was buried with full military honors in the British cemetery. King George V sent his condolences, and it was said that King Feisal watched the funeral procession from the balcony of his palace.

Endnotes

1. Georgina Howell, ed., Gertrude Bell: A Woman in Arabia (London: Penguin, 2015), p. 67.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Janet Wallach, Desert Queen (New York: Doubleday, 1996), p. 298.

5. Ibid., p. 299.

6. Howell, p. 208.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.