Finest Hour 196

“Mr. Churchill Was Admirable”

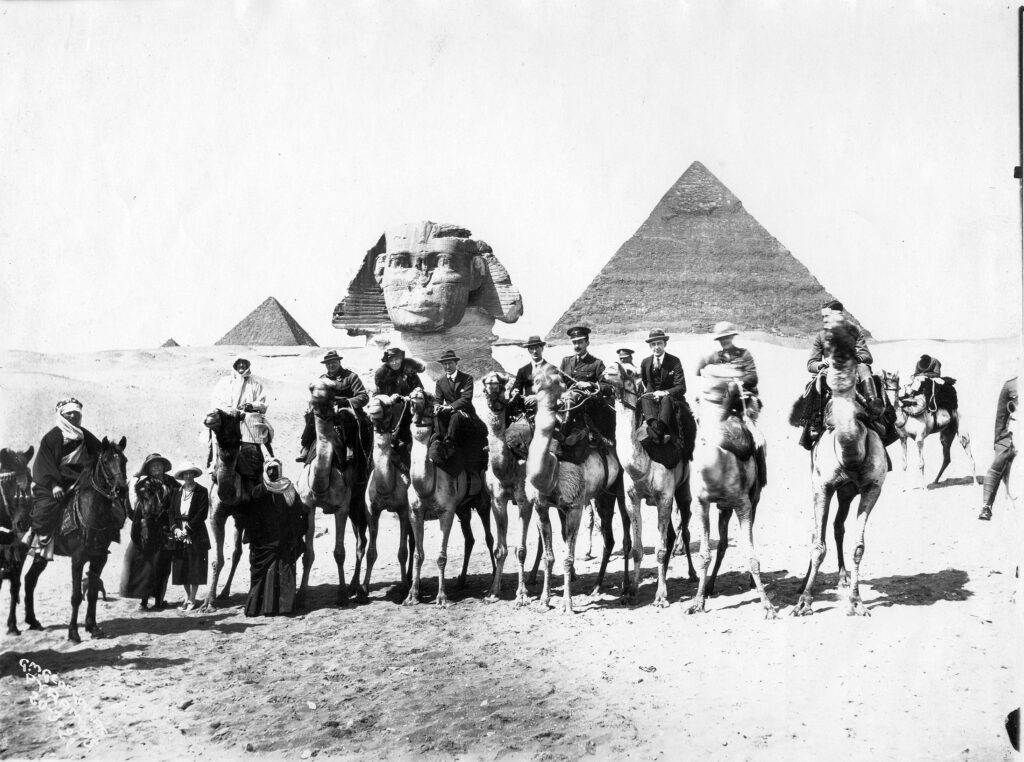

On camels (left to right): Clementine and Winston Churchill, Gertrude Bell, and T. E. Lawrence in front of sphinx and pyramids, during Cairo Conference, 20 March 1921. Photo by G. M. Georgoulas, Gertrude Bell Archive, Newcastle University, Pers_F_003.

June 14, 2023

Gertrude Bell as Adviser to Winston Churchill in Cairo, 1921

Finest Hour 196, Second Quarter 2022

Page 22

By Mark P. C. Jackson

Mark P. C. Jackson is Senior Lecturer in Archaeology, Head of Archaeology, and Manager of the Gertrude Bell Photographic Archive at Newcastle University.

When Winston Churchill took over as Secretary of State for the Colonies in January 1921 Britain was spending some thirty million pounds a year on the British Army in Mesopotamia.1 The enormous cost was receiving bad press, but the financial burden on both the British taxpayer and the wider Empire was a symptom of the underlying challenge—a sustainable future for Mesopotamia.

Following the end of the First World War and the fall of the Ottoman Empire, a reasonably stable security situation in Mesopotamia had degenerated by the summer of 1920. The British administration had struggled to maintain authority, and violent uprising had led “near to a complete collapse of society,” with the result that the government called the administration in Baghdad for a report.2

The Acting Civil Commissioner A. T. Wilson “entrusted responsibility for the preparation of A Review of the Civil Administration of Mesopotamia to Miss G. L. Bell CBE, a senior member of his staff.3 The report was published on 3 December 1920 and provided an account of the civil administration during the military occupation from 1914 until that year.

On 31 December, Prime Minister David Lloyd George and the Cabinet resolved to set up a new inter-departmental committee to recommend the establishment of a new department to take over the mandated territories and other territories in the Middle East from the Foreign Office, India Office, and War Office.

Churchill as Colonial Secretary

The Cabinet proposal made on the last day of 1920 went into effect on 14 February 1921. On the first day of March, in his new role as Secretary of State for the Colonies, Winston Churchill initiated the formation of the new department within the Colonial Office, which became responsible principally for Mesopotamia, Aden, and Palestine.4

In addition to continuing the existing practice of using revenue from the Government of India to carry a portion of the expenditure on the Middle East, the Cabinet agreed that the Secretary of State for the Colonies should begin by visiting Egypt to consult with British authorities in Palestine and Arabia. The Cairo Conference, which began on 12 March 1921, was chaired by Churchill. Negotiations over the next few days resulted in decisions that initiated much of the future direction of what was to become Iraq.5

The delegates from Mesopotamia were led by Sir Percy Cox, the High Commissioner, and included Gertrude Bell, who participated formally as Political Secretary. Also attending were T. E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”) and H. W. Young from the Middle East Department of the Foreign Office. Their combined role was instrumental in advising Churchill on the resulting strategy, which gave Britain’s support to the Emir Feisal ibn Hussain as the first monarch for the new state of Iraq. The delegates also contributed to the discussion on the future of the southern Kurdish regions.

Bell of Mesopotamia

By March 1921, when she attended the Cairo Conference, Bell had known Cox from their work in Mesopotamia for five years. Their collaboration together began in 1916, when Bell had arrived at Basra, sent to Cox with a recommendation from Charles Hardinge, Viceroy of India.6 She was to spend most of the next decade as a senior member of the administration in Mesopotamia.

Bell’s life up to that point was far from typical. Before the war between 1899 and 1914, she had made a series of expeditions lasting several months as an amateur archaeologist in what was then the Ottoman Empire. Funded by her father Hugh Bell, a wealthy industrialist, and with doors to the diplomatic circles opened by her step-mother’s family, Bell became familiar with the topography, monuments, and people of what are now Turkey, Syria, and Iraq, in particular.

In the summer of 1914, just before the outbreak of the First World War, Bell was one of the last Europeans to have been to Arabia. She returned via Baghdad from a long journey to Hayil, a route that she had mapped and photographed. Initially volunteering for the Red Cross on the Western Front, in November 1915 she was recruited for British Military Intelligence by D. G. Hogarth to Cairo along with several other archaeologists, including T. E. Lawrence, for what was to become the Arab Bureau.

Difficulties between the Bureau in Cairo and the administration responsible for Mesopotamia in Delhi led Bell to visit the Viceroy in India, who, as a result of their meeting, sent her with his recommendation to Cox. Her knowledge of the Arabic language gave her a substantial advantage over many of her British contemporaries, as she remarked in May 1916 some months after her arrival in Basra: “None of these people from India know Arabic and what that means in an Intelligence Dept. I leave you to guess.”7 Bell maintained and developed her influence, becoming increasingly central to those in authority by working both with senior members of the British administration and Arab leaders.

In 1918, following the Proclamation of Peace, Bell wrote to her father that “on two points they [the people in Iraq] are practically all agreed, they want us to control their affairs and they want Sir Percy as Commissioner. Beyond that all is divergence. Most of the town people want an Arab Amir but they can’t fix upon the individual.” The same day the Secretary of State for India wrote to Cox in Baghdad that “it is the policy of H.M. Government to aid in establishing native governments in the liberated areas and not to impose on the populations any form of governments which they dislike.”8 The following month Bell was upbeat in another letter home: “A. T. Wilson and I spend a considerable part of our time laying down acceptable frontiers—by request. It’s an amusing game when you know the country intimately, as I do, thank goodness, almost all of it. Was ever anything more fortunate than that I should have criss-crossed it in very nearly every direction?”9

In 1919 the Paris Peace Conference began, attended later by Emir Feisal and Lawrence as well as Bell and A. T. Wilson, the Acting Civil Commissioner. Bell wrote a memorandum, Self-Determination in Mesopotamia, sent to the India Office by Wilson, and, while he remained strongly against the idea of Arab rule, Bell came to understand the kind of state the nationalists working with Feisal were seeking.10

By September 1920, the British administration in Iraq was facing serious uprisings. Bell was pessimistic: “It’s true that we are largely suffering from circumstances over which we couldn’t have had any control. The wild drive of discontented nationalism from Syria and of discontented Islam from Turkey might have proved too much for us however far-seeing we had been; but that doesn’t excuse us for having been blind….We’re near to a complete collapse of society….How can we, who have managed our own affairs so badly, claim to teach others to manage theirs better? It may be that the world has now to sink back into dark ages of chaos, out of which it will evolve something, perhaps no better that what it had.”11

On 10 January 1920, Bell answered a call to visit Cox at his house in Baghdad; he had received a telegram from Churchill informing him of the need to withdraw troops from Mosul as soon as possible without giving the time Cox had requested to support the establishment of a government by Feisal, his proposed candidate. Cox and Bell were both of the opinion that Churchill’s proposal for such immediate withdrawal was not workable.12

Cairo Conference, March 1921

A few weeks later, Bell was part of the small delegation that travelled with Cox to advise Churchill in person. Cox, as High Commissioner of Mesopotamia, attended both military and political committees, as well as their joint meetings with Churchill as chairman. The membership of the political committee was much smaller than its military counterpart, and here we see the potential influence and authority of a very small group. In those meetings Churchill led discussions between Cox, Bell, Lawrence, and Young, with R. D. Badcock as secretary. Their aim was to establish a new state, ruled independently without the need for British troops, while the military committee worked on plans for the reduction of the army.

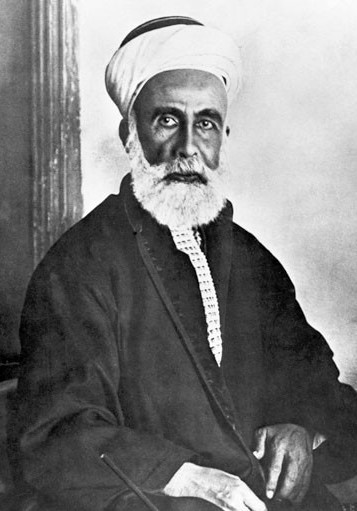

The memorandum drawn up in London prior to the conference makes clear that one of its goals was the selection of an Arab ruler for Mesopotamia and that Feisal was the preferred candidate. While the minutes of the political committee acknowledge six potential leaders to take over from the Provisional Government set up by Cox, they make clear that Cox and his colleagues indeed favoured a member of the family of the Sharif of Mecca over a candidate from Mesopotamia. Of the Sharif’s sons, Feisal had worked closest with the British during the Great War.

Cox cited Feisal’s experience of warfare, which placed him well for raising an army, together with his experience of the Allies, as qualifying him to rule. Lawrence spoke strongly in favour of Feisal. Apart from his personal knowledge of the man gained during the war, Lawrence recognized that Feisal had an inspiring personality that had the realistic potential to bring together disparate groups; for this task Lawrence saw Feisal better suited for Iraq than his brother Abdullah. Having come to a consensus on this conclusion, subsequent meetings considered how the British could ensure Feisal’s institution in Baghdad without being seen to impose him on the new state.

The conference minutes reveal Bell’s attention to the local political context. In the first meeting, she prompted Churchill to consider the role of prominent rebel leaders, and in the second she raised her concerns about the opposition that might be expected from Sayed Talib, one of the other candidates. Though she admitted this opposition would be negligible compared to the support anticipated for Feisal, her comments illustrate her efforts to present Churchill with an appreciation of the wider political situation. Later she suggested possible opposition might come also in the form of a movement in favour of a Commonwealth under the Presidency of the Naqib. These records show that Bell was prepared to raise in the meeting the potential consequences of their proposed action and the need to mitigate the possibility of their occurrence.

In the fourth meeting of the political committee, the Kurdish areas of Iraq were discussed around Kirkuk, Sulaimaniya, and districts north of Mosul. The minutes report that Cox put forward the argument that Southern Kurdistan was an integral part of Iraq and should be part of the country economically. Bell had suggested, and Cox agreed, that the people of Kirkuk would want to take part in the election and be represented in the Iraqi Parliament. Young disagreed and proposed instead that a separate state be set up for the Kurdish area administered by the British High Commissioner and not subject to the Government of Iraq. Lawrence argued also that the Kurdish areas should not come under an Arab government.

Having earlier stated that it was her view that within six months of its establishment the Kurds would want to join the Iraq Government, Bell lobbied for Mosul to be included in Iraq. Churchill was inclined to see the benefits to the British of a “friendly buffer state between Iraq and the Kurds.”13 While the minutes report that under the influence of the High Commissioner Churchill trusted that the two separate states of Kurdistan and Iraq might be brought together in the future under a single state, the recommendation from the conference was that the Kurdish area should stay under the direction of the High Commissioner, because of concerns that the Kurdish districts would not want to be subject to an Arab government. A force of Kurdish troops would be led by the British, ultimately to take over from the British in the frontier region, and Arab levies were to be expanded with Assyrian and Kurdish levies.

While Bell clearly attended the Cairo Conference, the minutes report relatively few contributions from her. It was Cox who held formal authority, and it his voice that comes across most loudly in the records. Nevertheless it has been argued recently that Bell had considerable influence on Cox’s thinking, especially on the idea that Kurdistan should be integral to the new state of Iraq.14 In August 1921, Feisal was crowned king, and by 1923 Churchill was able to celebrate the fact that the army in Mesopotamia had been reduced from forty battalions to just over ten percent of that number of battalions, with a reduction in their cost from over thirty million pounds to under five million per year.15

“In Bell’s eyes, Britain had to be exceptionally sensitive to Arab wishes in relation to Southern Kurdistan’s future. She and Cox agreed that encouraging Arab nationalism in the shape of sponsoring Arab territorial claims on Southern Kurdistan was the viable option for containment of Turkish nationalists’ and Bolsheviks’ threats to British interests in Mesopotamia.”16 For Cox, the lack of a leader appropriate in Southern Kurdistan was reason to incorporate the region within Iraq, in spite of the fact that the people there had rejected Arab government.17 The position of Cox and Bell against that of the others at Cairo continued to be played out in subsequent years, underpinned by their support for Iraq under Feisal’s government in Baghdad.

Bell herself was well pleased with the results. “I’ll tell you about our conference,” she wrote her sister Florence after it was all over. “We covered more work in a fortnight than has ever been got through in a year. Mr. Churchill was admirable, most ready to meet everyone halfway and masterly alike in guiding a big political meeting and in conducting small political committees into which we broke up.”18 Although these two remarkable personalities only crossed paths during the seminal Cairo Conference, their joint work has left the world a long legacy.

Endnotes

1. Winston S. Churchill, “Mesopotamia and the New Government” The Empire Review 58, July 1923, pp. 691–98.

2. Gertrude Bell, letter to Florence Bell, 5 Sept. 1920, Bell Archive, Newcastle University.

3. Gertrude Bell, A Review of the Civil Administration of Mesopotamia (London: HMSO, 1920), frontispiece.

4. Cabinet Report on the Middle East Conference held in Cairo and Jerusalem, March 12th– 30th 1921, Section I, Appendix I, 11 Jan. 1921, CAB/24/126/23, National Archives, London.

5. Ibid.

6. Gertrude Bell, letter to Florence Bell, 11 Feb. 1916, India Viceregal Lodge, Delhi, Bell Archive.

7. Gertrude Bell, letter to Florence Bell, 14 May 1916, G.H.Q. Basra, Bell Archive.

8. Peter Sluglett, Britain in Iraq: Contriving King and Country (London: Tauris, 2007), p. 24.

9. Gertrude Bell, letter to Hugh Bell, 6 Dec. 1918, Bell Archive.

10. Sluglett, p. 32.

11. Gertrude Bell, letter to Florence Bell, 5 Sept. 1920, Bell Archive.

12. Gertrude Bell, letter to Hugh Bell, 10 Jan. 22, Bell Archive.

13. Appendix 10, Cairo Conference. CAB/24/126/23_1.

14. Saad Eskander, “Gertrude Bell and the formation of the Iraqi State,” in C. Tripp and P. Collins, Gertrude Bell in Iraq: A Life and Legacy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 215–38.

15. Churchill, p. 696.

16. Eskander, citing Cox to Churchill, 21 June 1921, C0730/2, National Archives

17. Saad Eskander, “Southern Kurdistan under Britain’s Mesopotamian Mandate: From Separation to Incorporation, 1920–23” Middle Eastern Studies 37:2, 2001, pp. 153–80.

18. Janet Wallach, Desert Queen: The Extraordinary Life of Gertrude Bell (New York: Doubleday, 1996), p. 296.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.